APRIL 2022

Opportunities to

Reduce Food Waste

in the 2023 Farm Bill

Prevention

Recovery

Recycling Coordination

AUTHORS

The authors of this report are Emily M. Broad Leib, Joseph S. Beckmann, Ariel Ardura, Sophie DeBode, Tori Oto, Jack Becker, Nicholas

Hanel, and Ata Nalbantoglu of the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic (FLPC), along with Yvette Cabrera, Andrea Collins,

Darby Hoover, Madeline Keating, and Nina Sevilla of NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council), Samantha Goerger and Dana

Gunders of ReFED, and Stephanie Cappa, Alex Nichols-Vinueza, and Pete Pearson of World Wildlife Fund (WWF).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report would not have been possible without the advice and support of the many individuals and organizations with whom

we discussed the ideas provided herein or who provided input and feedback on our drafts, including Melissa Melshenker Ackerman

(Produce Alliance), Lesly Baesens (Denver Department of Public Health & Environment), Joe Bolick (Iowa Waste Reduction Center),

Linda Breggin (Environmental Law Institute), Bread for the World, Carrie Calvert (Feeding America), Cory Mansell (Center for

EcoTechnology (CET)), Darraugh Collins (Food Rescue U.S. - Detroit), Shirley DelRio, Paul Goeringer (University of Maryland College of

Agriculture & Natural Resources), Nora Goldstein (BioCycle), Eva Goulbourne (Littlefoot Ventures), Andy Harig (FMI–The Food Industry

Association), LaToyia Huggins (Produce Alliance), Bryan Johnson (City of Madison, Wisconsin - Streets Division), Sona Jones (WW

International), Wes King (National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC)), David Matthews-Morgan, Andrew Morse (Iowa Waste

Reduction Center), Stacie Reece (City of Madison, Wisconsin), Barbara Sayles (Society of St. Andrew), Niyeti Shah (WW International),

Rachel Shumaker (City of Dickinson, ND), Tom Smiarowski (University of Massachusetts Extension, Center for Agriculture, Food, and

the Environment), Latha Swamy (City of New Haven, CT, Food System Policy Division), Danielle Todd (Make Food Not Waste), Jennifer

Trent (Iowa Waste Reduction Center), Lorren Walker (Elias Walker), Renee Wallace (FoodPLUS Detroit), among others.

Report design by Najeema Holas-Huggins.

About the Harvard Law School Food Law and Policy Clinic

FLPC serves partner organizations and communities in the United States and around the world by providing guidance on cutting-edge

food system issues, while engaging law students in the practice of food law and policy. FLPC is committed to advancing a cross-sector,

multi-disciplinary and inclusive approach to its work, building partnerships with academic institutions, government agencies, non-

profit organizations, private sector actors, and civil society with expertise in public health, the environment, and the economy. FLPC’s

work focuses on increasing access to healthy foods, supporting sustainable and equitable food production, reducing waste of healthy,

wholesome food, and promoting community-led food system change. For more information, visit www.chlpi.org/FLPC.

About NRDC (Natural Resources Defense Council)

NRDC defends the rights of all people to live free from environmental harm in a clean, healthy, and thriving natural world. We combine the

power of more than three million members and online activists with the expertise of some 750 scientists, lawyers, and policy advocates

across the globe to ensure the rights of all people to the air, the water, and the wild. For more information, visit www.nrdc.org.

About ReFED

ReFED is a national nonprofit working to end food loss and waste across the food system by advancing data-driven solutions to the

problem. We leverage data and insights to highlight supply chain ineciencies and economic opportunities; mobilize and connect

supporters to take targeted action; and catalyze capital to spur innovation and scale high-impact initiatives. Our goal is a sustainable,

resilient, and inclusive food system that optimizes environmental resources, minimizes climate impacts, and makes the best use of the

food we grow. To learn more about solutions to reduce food waste, please visit www.refed.org.

About World Wildlife Fund

WWF is one of the world’s leading conservation organizations, working for 60 years in nearly 100 countries to help people and nature

thrive. With the support of 1.3 million members in the United States and more than 5 million members worldwide, WWF is dedicated to

delivering science-based solutions to preserve the diversity and abundance of life on Earth, halt the degradation of the environment,

and combat the climate crisis. Visit www.worldwildlife.org to learn more.

Suggested Citation:

Emily m. Broad lEiB, JosEph s. BEckmann Et al., harv. l. sch. Food l. & pol’y clinic (Flpc), nat. rEs. dEF. council (nrdc), rEFEd, &

World WildliFE Fund (WWF), opportunitiEs to rEducE Food WastE in thE 2023 Farm Bill (2022), https://chlpi.org/wp-content/up-

loads/2022/04/2023-Farm-Bill-Food-Waste.pdf.

Table of Contents

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................................................................................................i

INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................................................................................................1

FOOD WASTE PREVENTION...............................................................................................................................................................3

Standardize and Clarify Date Labels..........................................................................................................................................3

Launch a National Food Waste Education and Awareness Campaign.........................................................................5

Provide Funding to K-12 Schools to Incorporate Food Waste Prevention Practices in Their

Programs..............................................................................................................................................................................................7

Promote Food Education and Food Waste Education in K-12 Programming.............................................................8

Utilize Existing Federal Household-Level Food Education Programs to Increase

Food Waste Awareness...................................................................................................................................................................9

Provide Grant Funding for New Technologies to Reduce Food Spoilage and Food Waste................................11

Implement a Certification Program for Businesses that Demonstrate Food Waste Reduction.........................12

Provide Financial Incentives to Businesses for the Adoption of Technologies that

Reduce Food Waste by at Least 10%.......................................................................................................................................13

SURPLUS FOOD RECOVERY..............................................................................................................................................................14

Strengthen and Clarify the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act.......................................................14

Increase Funding Support for Food Recovery Infrastructure and for Post-Harvest

Food Recovery..................................................................................................................................................................................16

Oer Grant Resources and Procurement Programs to Increase Food Recovery from Farms...........................18

Encourage USDA Grant and Loan Recipients to Donate Surplus Food by

Incentivizing Food Donation......................................................................................................................................................20

Expand Federal Tax Incentives for Food Donation..............................................................................................................21

Instruct the USDA Risk Management Agency and Approved Crop Insurance

Providers to Better Support Gleaning.....................................................................................................................................22

FOOD WASTE RECYCLING................................................................................................................................................................24

Provide Grants to Support Proven State and Local Policies that Reduce Food Waste

Disposed in Landfills or Incinerators.......................................................................................................................................24

Provide Grants and Loans for the Development of Organic Waste Processing Infrastructure.........................26

Require Federal Food Procurement Contractors to Measure, Recover, Recycle, and

Prevent Food Waste in Federal Contracts............................................................................................................................29

Support Compost End Markets Through Crop Insurance Benefits and Increased

Federal Procurement of Compost Products.........................................................................................................................29

Encourage Diversion of Food Waste into Animal Feed Where Appropriate............................................................31

FOOD WASTE REDUCTION COORDINATION.............................................................................................................................33

Increase Funding for the USDA Food Loss and Waste Reduction Liaison and

Create a Broader Research Mandate........................................................................................................................................33

Provide Funding for the Federal Interagency Food Loss and Waste Collaboration.............................................34

Establish New Positions for Regional Supply Chain Coordinators at the USDA...................................................35

Appendix A: U.S. Food Loss & Waste Policy Action Plan Recommendations and

Additional Report Recommendations............................................................................................................................................37

Appendix B: Table of Recommendations and Implementation Opportunities by Title...............................................38

Appendix C: Table of Pending Federal Legislation....................................................................................................................40

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The United States produces and imports an abundance of food each year, but approximately 35% of it goes

unsold or uneaten.

1

Annually, 80 million tons of surplus food are not consumed. Of this, 54.2 million tons go to

landfill or incineration, or are left on the fields to rot.

2

Farmers, manufacturers, households, and other businesses

in the United States spend $408 billion each year to grow, process, transport, and dispose of food that is never

eaten.

3

This waste carries with it enormous economic, environmental, and social costs, but also represents great

opportunity. ReFED, a national nonprofit working with food businesses, funders, policymakers, and more, to

reduce food waste, analyzed 40+ food waste solutions, and found that the implementation of these solutions has

the potential to generate $73 billion in annual net financial benefit, recover the equivalent of 4 billion meals for

food insecure individuals, save 4 trillion gallons of water, and avoid 75 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions

annually.

4

The federal government has an important role to play in the continued eort to reduce food waste. In 2015, the

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

jointly announced the nation’s first-ever food waste reduction goal, aiming to cut food waste in the United States

by 50% by the year 2030.

5

While the food waste reduction goal is a step in the right direction, in order to make

this goal a reality, it is imperative for the federal government to make food waste reduction a legislative priority.

Congress has started to take these necessary steps. In 2018, for the first time ever, Congress included measures

in the Farm Bill to reduce food waste, for example, by clarifying liability protections for food donors, financing

food recovery from farms, encouraging food waste recycling through community compost funding, and better

coordinating food waste reduction eorts across the federal government.

6

Many of these programs were

suggested in the Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the 2018 Farm Bill report, on which this report is based.

7

While the inclusion of these programs was an important first step, there is significant room for improvement in the

2023 Farm Bill. The farm bill authorizes roughly $500 billion over five years in expenditures across the entire food

system, and the upcoming farm bill is poised to use a portion of this funding to build upon the successful pilot

programs launched in 2018 and ensure more comprehensive investment in food waste reduction.

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the 2023 Farm Bill details how Congress can take action to reduce food

waste and oers specific recommendations of provisions to include in the 2023 Farm Bill. Given the bipartisan

support for measures to reduce food waste,

8

the next farm bill provides an exciting opportunity to invest in food

waste reduction eorts for greater social, economic, and environmental benefits. This report breaks food waste

recommendations into four categories, based on whether they are intended to prevent food waste, increase food

recovery, recycle food scraps through composting or anaerobic digestion, or coordinate food waste reduction

eorts.

Below are a summary of the four categories and the top recommendations for each that are described in greater

detail later in this report as well as mentions of relevant pending federal legislation (that are also included in

further detail in Appendix C):

FOOD WASTE PREVENTION

Prevention eorts focus on interventions at the root causes of food waste—they locate

and address ineciencies in the food system and food related practices before excess

food is produced, transported to places where it cannot be utilized, or discarded rather

than eaten. More than 85% of greenhouse gas emissions from landfilled food waste

result from activities prior to disposal, including the production, transport, processing,

and distribution of food.

9

The greenhouse gas emissions embodied in the food wasted

by consumers and consumer-facing businesses account for more than 260 million

metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO

2

e) per year,

10

which is equivalent to the

annual emissions of 66 coal-fired power plants.

11

Food waste prevention eorts keep

millions of tons of food out of the landfill and have the most potential for environmental,

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

i

economic, and social benefits. Altogether, the food waste prevention policies discussed in this section have the

potential to annually divert nearly 7 million tons from landfills, while generating more than $27.4 billion each year

in net financial benefit.

12

Standardize and Clarify Date Labels

There is no federal regulation for date labels used on food. Instead, each state decides whether and how to

regulate date labels, leading to a patchwork of inconsistent regulations and myriad date labeling terms such as

“sell by,” “best by,” “expires on,” and “use by.” Manufacturers have broad discretion over what dates to ax to

their food products, often using dates that typically reflect food quality and taste rather than food safety. Yet

businesses, individuals, and even state regulators frequently misunderstand date labels and interpret them to be

indicators of safety, leading to the unnecessary waste of wholesome food. Some states even restrict or forbid

the sale or donation of past-date foods that are still safe to donate and eat. These inconsistent and misguided

state laws lead to wholesome foods unnecessarily being discarded rather than donated. In order to reduce

consumer confusion and the resulting food waste, the 2023 Farm Bill should standardize date labels through the

Miscellaneous Title or a new Food Waste Reduction Title.

Launch a National Food Waste Education and Awareness Campaign

American consumers alone are responsible for 37.2% of all U.S. food waste.

13

Research shows that while consumers

understand the importance of food waste reduction in the United States, they do not recognize their own role

in these eorts. So far there have been successful small-scale campaigns to educate consumers, but to really

move the needle, a coordinated, well-funded national campaign is needed. The 2023 Farm Bill can address and

correct wasteful practices by providing $7 million annually through 2030 for a national food waste education and

awareness campaign—with $3 million for research into eective consumer food waste reduction strategies and

$4 million for consumer-facing behavior change campaigns—within the Miscellaneous or a Food Waste Reduction

Title.

Relevant Pending Legislation

Food Date Labeling Act of 2021 (H.R. 6167, S.3324 117th Cong. 1st Sess., 2021); School Food Recovery Act of 2021 (H.R.

5459, 117th Cong. 1st Sess., 2021)

SURPLUS FOOD RECOVERY

Food recovery solutions aim to recover surplus food and redistribute it to individuals

experiencing food insecurity. Recovering surplus food within the supply chain and reducing

barriers to food donation could result in the recovery of roughly 2.3 million additional tons

of food each year and a net financial benefit of $8.8 billion.

14

Nearly half of this new food

recovery potential comes from farms, more than a third from restaurants, and the rest from

grocers and retailers.

15

Strengthen and Clarify the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act

Many businesses are reluctant to donate food because of perceived liability concerns associated with donation,

such as a food recipient getting sick.

16

To eliminate these barriers to surplus food donation, the 2023 Farm Bill

should strengthen and clarify the Bill Emerson Good Samaritan Food Donation Act, which protects food donors

from liability.

17

It should do so by delegating authority over the Act to the USDA and mandating that the USDA

publish regulations interpreting the Act. The 2023 Farm Bill should also modify the Act to protect donors who

donate directly to individuals and organizations that charge a small fee for donated food.

Increase Funding Support for Food Recovery Infrastructure and for Post-

Harvest Food Recovery

The USDA should expand investments in food recovery infrastructure and innovative food recovery models

to overcome barriers to increased food recovery and donation. To support the development of food recovery

operations, Congress should increase funding for food infrastructure eorts, either through new 2023 Farm

Bill investments or by making several funding initiatives from the COVID-19 response permanent. Additionally,

ii

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

it should continue supporting innovative food recovery models by increasing funding for the Community Food

Projects Competitive Grants Program within the Nutrition Title and earmarking a portion of the grants for

food recovery projects. Congress should also increase funding for the Local Agriculture Market Program in the

Horticulture Title, increase its applicability to food waste reduction beyond just “on-farm food waste,” and earmark

a portion of its funding for food waste prevention and recycling and food recovery.

Relevant Pending Legislation

Further Incentivizing Nutritious Donations of Food (or FIND) Act of 2022 (H.R. 7313, 117th Cong. 2nd Sess., 2022); Food

Donation Improvement Act of 2021 (H.R. 6521, S.3281, 117th Cong. 1st Sess., 2021); Fresh Produce Procurement Reform

Act of 2021 (H.R. 5309, 117th Cong. 1st Sess., 2021).

FOOD WASTE RECYCLING

Food waste is the largest component of landfills nationwide—contributing over 36 million

tons to landfills each year

18

and accounting for 24.1% of landfilled municipal solid waste.

19

Food

waste alone produces 4% of all U.S. greenhouse gas emissions per year.

20

Further, instead of

being wasted, these organic inputs could contribute to better soil matter and reduce soil loss,

contributing to a more circular economy. Despite improvements in food waste prevention and

recovery initiatives, some food is inevitably discarded. Recycling remaining food waste has

the annual potential to divert 20.9 million tons of food scraps from landfills and produce a net

financial benefit of $239.7 million.

21

The 2023 Farm Bill should support methods of food waste

management that are sustainable, economically beneficial, and limit the use of landfill space

and reliance on incinerators.

Provide Grants to Support Proven State and Local Policies that Reduce

Food Waste Disposed in Landfills or Incinerators

Landfills continue to be overburdened by food waste.

22

States and cities are running out of space to store organic

waste as they continue to rely on landfills to manage this waste.

23

Further, as food items decompose in landfills,

they release harmful greenhouse gases at alarming rates, which can cause potential harm to human health,

agriculture, and other natural ecosystems and resources.

24

State and local policies such as organic waste bans, waste diversion requirements, landfill taxes, and Pay-As-You-

Throw policies have been shown to move the needle on reducing food waste and are essential to divert food

waste from landfills and incinerators. When food waste generators that produce a certain threshold of food waste

(e.g., grocery stores and hospitals) are prevented from transporting organic waste to landfills or have a strong

financial reason not to waste food, they will make changes such as oering smaller portions, donating surplus

food, recycling food scraps, and repurposing their leftovers. The 2023 Farm Bill should provide $650 million in

yearly funding for ten years for state, local, and tribal governments, independently or as part of a public-private

partnership to plan or implement proven policies that reduce food waste in landfills and incinerators.

25

As part

of this program, Congress should require the USDA (in collaboration with EPA) to maintain a database of the

state and local food waste reduction policies that have proven success, and data on their impacts. Congress can

establish this program in the 2023 Farm Bill within the Miscellaneous Title or a dedicated Food Waste Reduction

Title.

Provide Grants and Loans for the Development of Organic Waste

Processing Infrastructure

In addition to implementing waste bans, waste diversion requirements, zero waste goals, and waste prevention

plans, state and local communities must also develop their organic waste processing capabilities to manage the

organic waste diverted from landfills and to realize the benefits of these strategies. Both compost and anaerobic

digestion infrastructure have the potential to convert food waste into productive soil amendments.

These organic waste processing capabilities are also costly. In the 2018 Farm Bill, Congress authorized the creation

of the Community Compost and Food Waste Reduction Project (CCFWR) to provide pilot funding for local

governments in at least ten states to study and pilot local compost and food waste reduction plans.

26

CCFWR

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

iii

funding enables localities to enhance their waste prevention capacities and has already fostered a positive impact

within communities.

27

Congress should build on the existing CCFWR program and adopt new strategies to develop

composting and anaerobic digestion infrastructure. In order to scale the program’s benefits, Congress should

increase the total and per project funding available for the CCFWR program in the next farm bill. In addition,

as CCFWR projects are generally small community projects, Congress should provide larger funding for the

development of new compost and anaerobic digestion facilities, by providing $200 million per year for ten years

in new composting infrastructure.

Relevant Pending Legislation

Cultivating Organic Matter through the Promotion Of Sustainable Techniques (or COMPOST) Act of 2021 (H.R. 4443,

S.2388, 117th Cong. 1st Sess. 2021); Zero Food Waste Act of 2021 (H.R. 4444, S.2389, 117th Cong. 1st Sess. 2021).

FOOD WASTE REDUCTION COORDINATION

Data and research on food waste are critical to providing insight on areas that future

policymaking should prioritize. A lack of comprehensive research and federal agency

coordination in this space prevents eective management of national resources to

address food waste. In the 2018 Farm Bill, Congress established a USDA Food Loss and

Waste Reduction Liaison, a welcome step towards reducing food waste and increasing

food recovery at the federal level. The 2023 Farm Bill should build upon this by further

developing and funding food waste reduction coordination.

Increase Funding for the Food Loss and Waste Reduction Liaison and

Create a Broader Research Mandate

The Food Loss and Waste Reduction Liaison (the Liaison) fills an important role for federal food waste reduction.

The Liaison coordinates food waste reduction eorts across agencies, researches and publishes research on

sources of food waste, supports organizations engaged in food loss prevention and recovery, and recommends

innovative ways to promote food recovery and reduce food waste.

28

However, the Liaison only receives enough

funding to sta the individual Liaison position with no funding for additional support sta, which inhibits the

Liaison’s ability to fulfill their statutory mandate.

29

Congress should increase the funding and develop the Liaison

position into a Food Loss and Waste Oce, so that there are more sta and capacity to carry out the duties set

out in the farm bill. Congress should also identify modernizing and expanding national food waste data and farm

food waste loss measurement as explicit goals for the Liaison, using the additional funding provided.

Provide Funding for the Federal Interagency Food Loss and Waste

Collaboration

In 2018, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the USDA, and the EPA launched an interagency

task force known as the Federal Interagency Food Loss and Waste Collaboration (the Collaboration) that

is committed to working towards the national goal of reducing food loss and waste by 50% by 2030.

30

The

Collaboration plays a vital role in the federal government’s involvement in food loss and waste reduction eorts.

Congress should authorize $2 million in annual funding for the Collaboration in the 2023 Farm Bill to better

position it to meet the United States’ 2030 food waste reduction goal.

31

Congress should require a broader

set of federal agencies to engage in the Collaboration such as the Department of Defense, the Department of

Transportation, the Department of Homeland Security, the Department of Education, and the General Services

Administration, among others. Congress should also require the Collaboration to deliver regular reports to

Congress on its progress towards achieving the national food waste reduction goal. These provisions can be

included in the Miscellaneous Title or in a new Food Waste Reduction Title.

Relevant Pending Legislation

National Food Waste Reduction Act of 2021 (H.R. 3652, 117th Cong. 1st Sess. 2021).

vi

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

The amount of food wasted in the United States

poses an enormous problem. Even though an

abundance of food is produced and imported in the

United States each year, about 35% of it goes unsold

or uneaten.

32

This means that annually, 80 million

tons of surplus food are not consumed. Of this, 54.2

million tons go to landfill or incineration, or are left

on the fields to rot.

33

Food loss and waste carries

enormous economic, social, and environmental

costs. Farmers, manufacturers, households, and

other businesses in the United States spend $408

billion each year to grow, process, transport, and

dispose of food that is never eaten.

34

Producing

food that ends up uneaten consumes 21% of

all freshwater, 19% of all fertilizer, and 19% of all

cropland used for agriculture in the United States.

35

Food waste generates about 270 million metric tons

of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO

2

e) greenhouse

gas emissions each year, the same as 58 million

passenger vehicles.

36

Despite the surplus of food produced, 10.5% of

American households faced food insecurity in 2019

and 2020, both before and after the COVID-19

pandemic began.

37

While the food insecurity rate

did not rise in 2020 because of the massive federal

investment in financial and direct assistance, the

pandemic exposed the need for food system

reform to ensure that our food supply can adapt

and continue to serve the needs of Americans

even when faced with unprecedented disruptions.

The amount of food that goes to waste each year

makes little sense when paired with the data on

the number of food insecure households. In fact,

according to the United States Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA), significantly more food is

wasted than would be required to feed every food-

insecure individual in the United States.

38

Reducing food waste is an important area for

resource conservation and climate change

mitigation that remains underdeveloped in federal

policy. However, in recent years, the federal

government has initiated eorts that acknowledge

its important role in the eort to reduce food waste.

In 2015, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)

and the EPA jointly announced the nation’s first-ever

food waste reduction goal, aiming to halve U.S. food

waste by 2030.

39

In 2018, the USDA, the EPA, and

the United States Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) signed an Memorandum of Understanding

to work together towards this goal.

40

In 2019, these

three agencies launched the Federal Interagency

Food Loss and Waste Collaboration (formerly

the Winning on Reducing Food Waste Federal

Interagency Collaboration) which set priority actions

to reduce food loss and waste, including enhancing

interagency coordination, increasing consumer

education and outreach eorts, and improving

coordination and guidance on food loss and waste

measurement.

41

State and local actors also are recognizing and

acting on the need for reform. At the local level,

many cities, including New York, Austin, San

Francisco, and Washington, D.C., promote food

waste reduction through creative initiatives to

reduce and better manage food waste.

42

For

example, San Francisco introduced the first ever

mandatory composting requirements for businesses

and residents in 2009.

43

Since then, at least seven

large cities or counties followed San Francisco’s

lead and implemented organic waste bans or

mandatory organic waste recycling laws.

44

States

have also implemented a variety of policies to

reduce food waste. These include tax incentives for

food donation,

45

organic waste bans,

46

and liability

protections for food donors and food recovery

organizations that exceed the federal floor.

47

Reducing food waste has unique bipartisan appeal

because it can simultaneously increase profits

and eciencies across the food system, increase

access to wholesome food, and protect the planet

from the harmful environmental consequences

associated with wasted food. According to an

analysis by ReFED, a national nonprofit working

with food businesses, funders, policy makers, and

more, to reduce food waste, implementing 40

priority food waste solutions has the potential to

generate $73 billion in annual net financial benefit,

recover the equivalent of 4 billion meals for food-

insecure individuals every year, and create 51,000

jobs over ten years.

48

Adding to these economic

and social benefits, food waste solutions also have

the potential to save 4 trillion gallons of water and

avoid 75 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions

annually, among other environmental benefits.

49

In order to meet our national food waste reduction

goal, the federal government must make food

waste reduction a priority in all of its policy areas.

INTRODUCTION

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

1

Of particular relevance is the farm bill. Passed

every five years, the farm bill is the largest piece

of food and agriculture-related legislation in the

United States and provides a predictable and visible

opportunity to address food waste on a national

scale. With food waste becoming a major focus

in both states and the federal government, this

legislation oers an opportunity to address multiple

sectors of the food and agricultural system and

eect system-wide change to reduce food waste.

In 2018, Congress, for the first time ever, included

measures related to food waste in the farm bill.

50

These provisions are enumerated in the first Text

Box above and are described in more detail as

relevant throughout this report. Many of these

provisions were suggested in the Opportunities to

Reduce Food Waste in the 2018 Farm Bill report, on

which the current report is based.

These provisions oer an important starting point

for investing the resources needed to meet our

national food waste reduction goals. This report

oers opportunities for Congress to build upon its

noteworthy achievements in the 2018 Farm Bill by

expanding the pilot programs and grants initiated

in the 2018 Farm Bill and developing noteworthy

and necessary new programs. Building from the

preliminary funding in the 2018 Farm Bill, the 2023

Farm Bill is poised to help the federal government

take more eective and wide-ranging action to

reduce food waste. Food waste reduction programs

could be included in a dedicated Food Waste

Reduction Title or by modifying existing titles and

programs to incorporate food waste reduction

as a priority. Several provisions presented in this

report could alternatively be implemented through

standalone federal legislation.

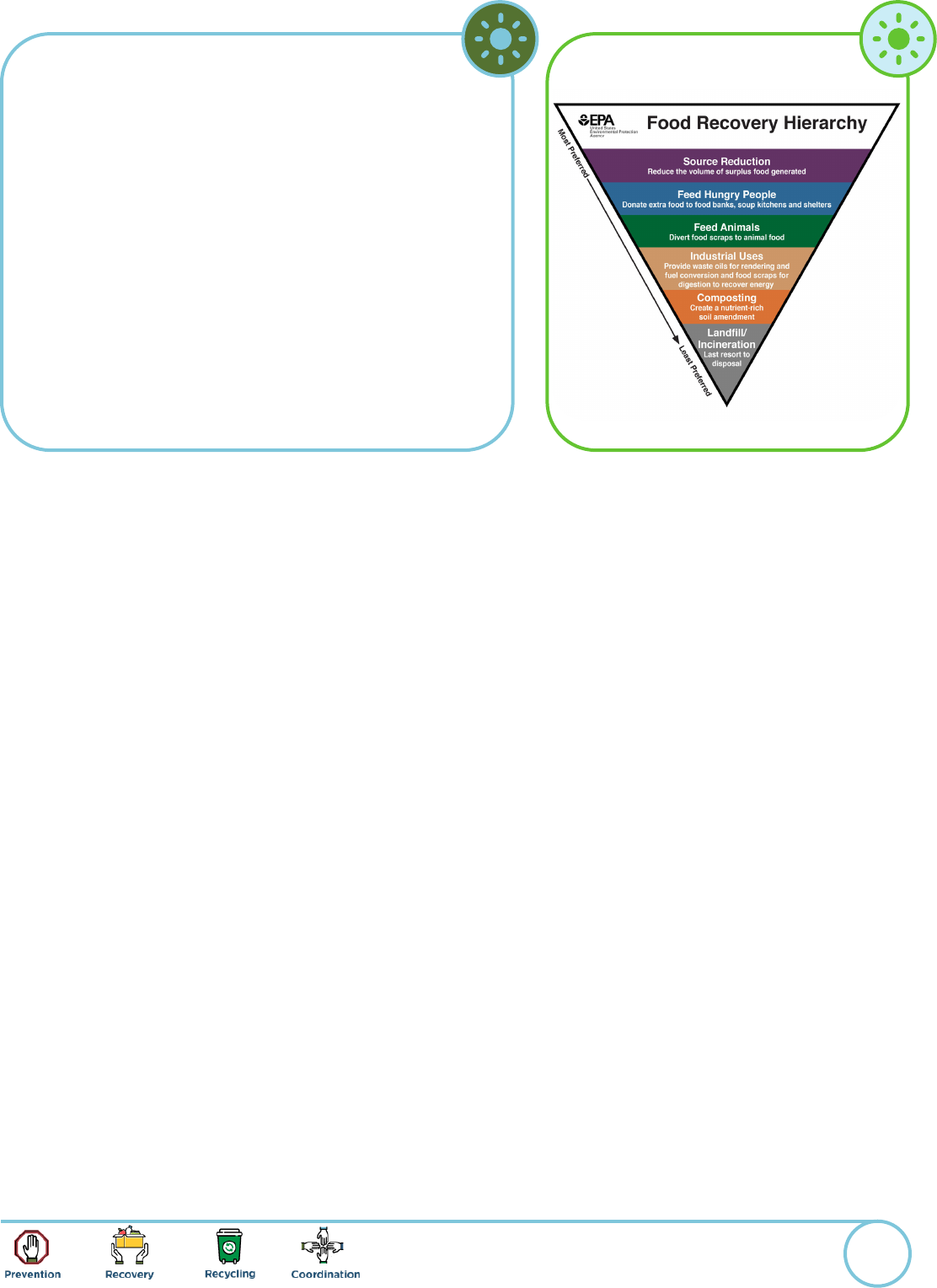

The recommendations presented in this report are

organized to reflect the priorities outlined in the

EPA Food Recovery Hierarchy (pictured above).

51

As in the Food Recovery Hierarchy, this report

highlights food waste prevention as the most

important goal and begin by making proposals to

prevent waste. Waste prevention eorts aim for

intervention at the root causes of food waste—

they locate and address ineciencies in the food

system and food related practices before excess

food is produced, transported to places where it

cannot be utilized, or discarded rather than eaten.

Waste prevention eorts keep millions of tons of

food out of the landfill, and altogether, the waste

prevention policies discussed have the potential

for the most considerable environmental benefit.

Next, the report outlines opportunities to facilitate

redirection of wholesome

surplus food to food-

insecure individuals by connecting farmers, retailers,

or food service establishments with food banks,

food rescue organizations, community organizations

that provide food, emergency feeding operations,

and other intermediaries (collectively referred

to as “food recovery organizations”). Then, the

report outlines recommendations for supporting

recycling food scraps through composting or

anaerobic digestion, rather than disposing of waste

in landfills or incinerators. The report concludes

with recommendations to coordinate and streamline

food waste reduction eorts and elevate food waste

reduction to be a federal priority. Taken together,

the recommendations presented in this report can

2

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

In the 2018 Farm Bill, Congress responded for the

first time ever to the pressing need for action on food

waste reduction, with an unprecedented inclusion of

various food waste related programs and funding.

Food Waste Provisions Included in the 2018 Farm Bill:

· Pilot Project to Support State and Local

Composting and Food Waste Reduction Plans

· Grant Resources for Food Recovery Infrastructure

Investments

· Food Loss and Food Waste Liaison and Study on

Food Waste

· Food Donation Standards for Liability Protections

· Milk Donation Program

· Local Agriculture Marketing Program

· Spoilage Prevention

· Carbon Utilization and Biogas Education Program

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

3

strengthen the economy, preserve the environment,

help withstand disasters—like pandemics—and

improve the lives of millions of Americans, all

by reducing the unnecessary waste of healthy,

wholesome food that can be eaten, and by recycling

remaining food scraps.

Annual potential to divert 582,000 tons

of food waste, reduce 2.73 million metric

tons of CO

2

e, and save 162 billion gallons of

water, with a net financial benefit of $2.41

billion

54

ISSUE OVERVIEW

A major driver of food waste is confusion over date

labels.

55

Consumers face an array of unstandardized

labels on their food products, and many people

throw away food once the date passes because

they mistakenly think the date is an indicator

of safety. However, for most foods the date is a

manufacturer’s best guess as to how long the

product will be at its peak quality. When consumers

misinterpret indicators of quality and freshness

for indicators of a food’s safety, this increases the

amount of food that is unnecessarily discarded.

There is currently no federal scheme regulating date

labels on food products other than infant formula.

56

Congress has given general authority to the FDA

and the USDA to protect consumers from deceptive

or misleading food labeling.

57

Both the USDA

58

and

the FDA

59

published recommendations regarding

the language to be used for date labels, but neither

agency has used its authority to implement a

comprehensive, mandatory regulatory scheme.

In the absence of federal regulation, states have

enormous discretion to create regulatory schemes

for date labels, resulting in high variability. Most

states regulate some food items, while few states

have created a comprehensive date labeling

scheme, and some do not regulate date labels at

FOOD WASTE PREVENTION

Standardize and Clarify Date

Labels ★

U.S. Food Loss & Waste Policy Action Plan:

On April 6, 2021, the Harvard Law School Food Law & Policy Clinic (FLPC), NRDC (Natural Resources

Defense Council), ReFED, and World Wildlife Fund (WWF)—along with many additional supporters,

including the American Hotel and Lodging Association, Compass Group, Food Recovery Network,

Google, Hellmann’s Best Foods, Hilton, Hyatt, Marriott International, the Kroger Company, Unilever,

several local government agencies, and other businesses and non-profit organizations

52

—published

the U.S. Food Loss & Waste Policy Action Plan for Congress & the Administration (Action Plan).

53

The Action Plan calls upon Congress and the Biden administration to take ambitious action to

achieve the goal of cutting U.S. food loss and waste in half by 2030. It recommends five key policy

recommendations ranging from investing in infrastructure and programs that measure and prevent

food waste to standardizing date labeling at the federal level. The recommendations in this report that

are also included in the Action Plan, and thus endorsed by a broad set of partners, are notated with ★

symbol. They are also listed together in Appendix A.

all.

60

Some states even restrict or forbid the sale

or donation of past-date foods, even though most

date labels are not safety indicators, creating

unnecessary barriers to the donation of safe food.

61

Manufacturers generally are free to select whether

to use a date label, which explanatory phrase they

will use (e.g., “best by,” “use by,” “best before,”

or “sell by”), and how the timeframe for the date

will be measured. Manufacturers use a variety of

methods to determine the timeframe for label dates,

almost all of which are intended to reflect when the

food will be at its peak quality and are not intended

as safety indicators.

62

Yet businesses, individuals,

and even state regulators frequently misinterpret

the dates to be indicators of safety, leading to the

unnecessary waste of wholesome, past-date food.

63

ReFED estimates this confusion accounts for 20% of

consumer waste of safe, edible food—approximately

$29 billion worth of wasted consumer spending per

year.

64

Federal standardization of date labels has the

potential to dramatically reduce food waste in

the United States. According to ReFED’s Insights

Engine, standardizing date labels is one of the most

cost-eective ways to reduce food waste, with the

potential to divert 582,000 tons of food waste per

year from landfills, and the opportunity to provide

$2.41 billion per year in net economic value.

65

RECOMMENDED DATE LABELING SCHEME

Congress should standardize and clarify date labels

by establishing a dual date labeling scheme that

applies to all food products nationally and limits

date labeling language to two options: either a label

to indicate food quality or a label to indicate food

safety. This would align with the preexisting industry

Voluntary Product Code Dating Initiative established

in 2017 by The Food Industry Association (FMI)

(formerly the Food Marketing Institute) and the

Consumer Brand Association (CBA) (formerly

the Grocery Manufacturers Association), which

recommends manufacturers use the term “BEST

If Used By” where foods are labeled as a quality

indicator, and the term “USE By” on foods labeled

to indicate that they may pose a safety risk if

consumed after this date.

66

Date labels used to

signify food quality, which comprises most date

labels on food products, should be required to use

the language “BEST If Used By.” For foods that

increase in safety risk past the date, manufacturers

should use a safety date, indicated with the

language “USE By.”

This would build on the momentum already

underway. According to CBA, their members self-

reported that 87% of products were using these

streamlined labels as of 2018, less than two-years

after CBA began the initiative.

67

Further, federal

agencies recommend quality labels use the “Best

If Used By” language, as evidenced by the USDA

Food Safety Inspection Service (FSIS) 2016

recommendation that food manufacturers and

retailers use this label to communicate quality

68

and

the FDA’s 2019 open letter supporting voluntary

eorts to use “Best If Used By” to indicate quality.

69

Further, this dual date labeling scheme is ideal for

communicating eectively with consumers. A 2016

national consumer survey conducted by FLPC, the

National Consumers League, and Johns Hopkins

University found that “best if used by” was the

language best understood by consumers to indicate

quality, while “use by” was one of two phrases that

best communicated food safety.

70

Requiring standard date labels would align the

United States with its peer countries. Internationally,

the Codex Alimentarius 2018 update, General

Standard for the Labelling of Prepackaged Foods,

sets out a dual date labeling scheme as the model

practice.

71

The Codex Alimentarius is a set of

international food standards developed by the Food

and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

(FAO) and the World Health Organization (WHO).

Aligned with the Codex standards, the European

Union requires companies to use a safety-based,

“use by” date label for foods that are considered

“highly perishable,” and unsafe to consume after

the date. All other foods use a quality-based, “best

before” date label, after which food may still be

perfectly safe to consume and donate.

72

In addition to standardizing date labels, federal

action is also needed to preempt state restrictions

on the sale or donation of food that is past its

quality date. Currently, 20 states restrict the sale or

donation of past-date foods, even when the dates

on those foods have no bearing on safety, leading to

unnecessary waste.

73

However, since only past-date

foods bearing the “USE by” date label would pose a

safety risk, the sale and donation of foods past the

“BEST if Used By” date should be permitted.

To support the implementation of this change,

Congress should instruct the FDA and the USDA to

collaborate to inform consumers about the update,

explicitly defining what these two labels mean in an

education campaign.

74

Ensuring that consumers are

aware of the new date labels and their meanings

will help prevent unnecessary discarding of safe,

4

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

wholesome food. This could be included in the

national food waste education campaign discussed

in Section I(B) of this report.

IMPLEMENTATION OPPORTUNITY

The next farm bill should take the easy

and cost-eective step to reduce food

waste by standardizing and clarifying

date labels with a uniform, nationwide

policy that applies to all food

products. This standardization should

take the form of the two labels: “BEST if Used By” to

indicate quality, and “USE By” to indicate safety. The

initiative should also include a consumer education

campaign.

The farm bill has previously addressed food labeling

concerns,

75

and is an appropriate vehicle for

standardizing date labels. This scheme should be

implemented through a new Food Waste Reduction

Title or in the Miscellaneous Title. Language

implementing the above recommendations could

be taken from the bicameral, bipartisan Food Date

Labeling Act of 2021.

76

Launch a National Food Waste

Education and Awareness

Campaign ★

Annual potential to divert 1.38 million tons

of food waste, reduce 7.41 million metric

tons of CO

2

e, and save 281 billion gallons of

water, with a net financial benefit of $6.08

billion

77

ISSUE OVERVIEW

American consumers waste an estimated 30 million

tons of food each year—accounting for about

37.2% of the food that goes to waste.

78

While many

consumers understand the importance of food

waste reduction, they generally do not recognize

their own role in reducing food waste.

79

American

consumers “perceive themselves as wasting little,

with nearly three-quarters reporting that they

discard less food than the average American.”

80

Most consumers report that they discard less than

10% of their food and believe that much of their

food waste is unavoidable.

81

However, the average

household wastes 31.9% of the food it buys.

82

This mismatch regarding consumers’ individual

contribution to food waste and their perception

of the quantity of their own waste demonstrates a

problematic lack of awareness.

NATIONAL FOOD WASTE EDUCATION CAMPAIGN

Congress can promote national food waste

education and awareness through a public

awareness campaign. ReFED estimates that a

national consumer education campaign is one of

the most cost-eective solutions to reduce food

waste, with the potential to divert 1.38 million

tons of food annually and create $6.08 billion net

economic value.

83

Because consumers unknowingly

produce a massive amount of food waste, a national

food waste awareness campaign should be geared

towards increasing consciousness of the issue

and changing consumer behavior. This campaign

should incorporate elements of behavioral science

to illustrate how much food goes to waste in

households across the country, highlight methods

for preserving and storing foods, provide consumers

tips to identify whether food is still safe and edible,

and teach consumers how to compost food scraps.

84

Evidence indicates that a national education

campaign has tremendous potential to impact

consumer behavior. National education campaigns

eectively changed United States consumer

behaviors in other areas and consumer food waste

practices in other countries. Domestically, the

United States Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention’s (CDC) nine-week, national anti-smoking

education campaign, “Tips from Former Smokers,”

motivated almost 2 million Americans to attempt to

quit smoking.

85

In the United Kingdom, the Waste

and Resources Action Programme’s (WRAP) “Love

Food Hate Waste” nationwide campaign reduced

consumer food waste by 21% in five years.

86

The

program cost £26 million (~$34.43 million USD) over

five years to implement but was responsible for £6.5

billion (~$8.6 billion USD) in savings to households

in avoided food costs, as well as £86 million

(~$114 million USD) in savings to U.K. government

authorities in avoided waste disposal costs.

87

Altogether, the initiative reaped a total benefit-

cost ratio of 250:1. Between 2015 and 2018, the

U.K. avoided 1.6 million tons of greenhouse gases

and diverted 480,000 tons of food waste directly

attributable to the nationwide campaign.

88

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

5

A national food waste education campaign in the

United States could similarly cultivate a cultural

movement against food waste. In 2016, the Ad

Council and NRDC launched “Save the Food,”

a public awareness campaign that encourages

Americans to reduce food waste.

89

“Save the Food”

has been featured on television, radio, billboards,

and waste trucks in several large cities across the

country, including Chicago and New York City.

90

As of 2019, more than $111 million of media space

was donated, and survey results demonstrated that

those aware of “Save the Food” ads were more

likely to say that they had reduced the amount of

food they had thrown away in the prior 6 months,

compared to those not aware of the ads.

91

While the “Save the Food” campaign is a first step,

consumer education on food waste is needed

on a larger national scale. With many American

consumers still unaware of the impacts of food

waste as well as their contribution to the issue,

a nationwide targeted campaign could unify the

messaging regarding consumer food waste and

ensure that it reaches all Americans.

A national food waste education campaign will only

be eective if it is properly targeted at consumers

with well-tested messaging. It is essential that

research be conducted to consider consumer

insights and develop campaign approaches that

resonate with target markets and incorporate

elements of behavioral science to optimize

campaign eectiveness.

92

Research should go

towards investigating which population segments

to target, understanding how to best target them,

and determining which strategies are most eective

in changing consumer habits, rather than just

increasing awareness of the issue.

93

The research

can also help identify the best messengers, which

likely will dier across segments and markets (i.e.,

using celebrities or television shows that resonate

with children to target the youth audience, social

media to target young adults, and more traditional

advertising streams to target adults), even though

the messages themselves will be consistent. Pilot

projects with strong assessment tools, including

waste audits in communities where the campaigns

are piloted, should be used before implementation

of a full campaign to maximize eectiveness.

In the UK, WRAP used a consumer insight-driven

research program to determine that 18- to 35-year-

old people waste more food than any other age

group, making them the ideal target, and the best

way to interact with this group was through digital

media messaging.

94

This type of targeting has

also been used eectively at a smaller scale in the

United States. In the City and County of Denver,

the Department of Public Health and Environment

has been integrating Community Based Social

Marketing (CBSM) strategies targeted specifically

at reducing food waste from leftovers.

95

The United

States should learn from the targeting strategies

used in these campaigns to optimize the consumer

education and awareness campaign.

The Sustainable Management of Food program

at the EPA created an implementation guide and

toolkit for its food waste education program:

Food: Too Good to Waste.

96

The guide is

intended for community organizations and local

governments interested in reducing food waste

from households.

97

The guide oers advice on how

to select a population to target and execute the

education campaign. While the EPA has produced

these helpful resources, they have not launched

a full-scale consumer education campaign that

is necessary to eectively reduce food waste

nationally. The federal government, led by the USDA

working with the EPA, could leverage these existing

assets and research related to consumer outreach

and behavior change when starting a national food

waste education and awareness campaign.

IMPLEMENTATION OPPORTUNITY

The next farm bill should instruct

the USDA in collaboration with EPA

to launch a national food waste

education and awareness campaign.

A widespread consumer education

campaign should be supported

with funds appropriated through a Food Waste

Reduction Title or through the Miscellaneous Title.

Congress should appropriate $7 million annually

through 2030, with $3 million for research into

eective consumer food waste reduction strategies

and $4 million into consumer behavior change

campaigns.

6

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

Provide Funding to K-12

Schools to Incorporate Food

Waste Prevention Practices in

Their Programs

Annual potential to divert 7,060 tons of

food waste, reduce 33,600 metric tons of

CO

2

e, and save 1.69 billion gallons of water,

with a net financial benefit of $13.2 million

98

ISSUE OVERVIEW

Every year tons of wholesome food are wasted in

schools, costing the federal government as much as

$1.7 billion annually.

99

This waste undermines eorts

to address food insecurity, mitigate environmental

degradation, and achieve food sustainability.

Schools provide close to 100 million meals to

children each day as part of the National School

Lunch Program (NSLP).

100

In the spring of 2019,

WWF, with support from The Kroger Co. Foundation

and the EPA Region 4 (Southeast), analyzed food

waste in 46 schools in nine cities across eight

states.

101

The report found that the schools wasted

39.2 pounds of food per student annually.

102

Based

on these numbers, WWF extrapolates that schools

participating in federal meal programs could waste

360,000 to 530,000 tons of food each year.

103

The environmental impact of food waste in schools

is significant. Given that over 100,000 schools

participate in the NSLP, the food waste translates to

1.9 million metric tons of CO

2

e of greenhouse gases

and over 20.9 billion gallons of embedded water

(the water that went into producing the food that

went to waste).

104

Given the scale of waste resulting

from school meal programs, schools should be a

focal point for food waste education and reduction

eorts.

SUPPORTING FOOD WASTE REDUCTION

STRATEGIES IN SCHOOLS

Food waste in schools occurs for several reasons,

including incorrect portion sizes and situational

issues such as unpleasant eating environments and

insucient time periods for students to consume

their meals.

105

There are several ways to address

these issues; however, schools often struggle with

implementation due to costs, a lack of guidance on

how to adopt the changes, or insucient program

funding from the government.

Congress can support schools in conducting food

waste audits, student surveys, and other methods

to gather data on the types and quantity of food

thrown away in school cafeterias. Food waste

auditing helps administrators understand the scope

of their food waste problem and identify specific

areas for improvement.

106

In a 2019 study analyzing

food waste at 46 schools in eight states, WWF

found that students at each school were producing

approximately 40 pounds of food waste per year,

which is 9% higher than average Americans waste

in homes (normalized by meals).

107

Once informed

by their waste baseline, the schools conducted six

weeks of food waste audits and recorded a total

average waste reduction of 3%, with elementary

schools seeing a greater reduction at 14.5%. Of the

waste types measured including fruit and vegetable,

milk, and other organic wastes, milk waste saw the

greatest decrease with an average of 12.4%.

108

Yet, many schools currently lack the funding to take

on an auditing project. Even a $10-20 million grant

program would help many schools reduce their

food waste and change their cafeteria practices

to ensure more food is eaten and not wasted. The

program can build on the School Food Waste

Reduction Grant Program proposed in the bipartisan

School Food Recovery Act of 2021 (SFRA).

109

The

SFRA seeks to establish a similar competitive grant

program for local educational agencies to achieve

food waste reduction goals. Grant programming

directed at reducing school food waste will not only

provide schools with needed funds to administer

specific programs, including audits, but it will

also encourage schools to devote more time and

attention to food waste, and reward schools for

engaging in these beneficial activities.

Once schools conduct audits and better understand

the quantity of food waste they produce, they

can introduce strategies proven to be eective

in reducing food waste including longer lunch

periods,

110

share tables,

111

and collaborating with

students to improve meals.

112

In addition to support for schools undertaking food

waste audits, any funding or incentive for schools to

conduct food waste audits, measure their waste, and

take actions to reduce it or to redirect or donate

surplus food could help move schools towards

accounting for and changing their practices to be

more sustainable. This is particularly true in schools

utilizing additional grant funding for food service or

educational programs.

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

7

To ensure that state and local health inspectors are

aware of food waste policies in schools—specifically

food donation and share tables, which may raise

initial food safety concerns—Congress should

mandate that the USDA educate ocials about how

these strategies work and that they are permissible.

MANDATING AN OFFER VERSUS SERVE MODEL

ACROSS THE SCHOOL SYSTEM

When students are forced to take food they do not

plan to eat, food is inevitably wasted. To remedy

this problem, the USDA encourages schools to

adopt the “Oer Versus Serve” (OVS) model

113

which

allows students the opportunity to choose desired

components of their NSLP and School Breakfast

Program (SBP) meals to reduce food waste.

114

For

schools to participate in NSLP and SBP, they must

abide by federal and state rules on nutrition and

food procurement.

115

Meals that are eligible for NSLP

reimbursement must consist of five components:

fruit, vegetable, whole grain, meat/alternative, and

milk.

116

The OVS policy allows students to decline up

to two of these five components if they take either a

fruit or vegetable.

117

By contrast, students in schools

without an OVS policy would be required to accept

all five components, regardless of whether they

intend to eat all the foods they are given.

Confusion surrounding the OVS policy leads

to waste when schools mistakenly believe that

students must elect to take a certain component

of the meal, for example milk, for the meal to

be reimbursable under federal regulations.

118

However, while milk must be oered, students are

not required to take that option.

119

This confusion

contributes to up to 45 million gallons of milk waste

in school cafeterias nationwide.

120

Currently OVS is mandatory for high schools and

optional for elementary and middle schools, which

may explain the higher rates of food waste in the

lower grade levels.

121

Implementing this model across

all schools would reduce the immense amount

of waste produced in schools. The USDA should

provide simple and clear instructions to schools

implementing this program to avoid confusion and

misunderstanding of the current rules that may

lead to food waste. These instructions should be

accompanied by an awareness program to increase

understanding of the policies targeting both

students and school sta (such a program may be

as simple as posters explaining the requirements to

hang in the lunchroom).

IMPLEMENTATION OPPORTUNITY

In the next farm bill, Congress should

lower the financial burden on school

food waste reduction eorts by

providing dedicated grants to conduct

food waste audits and implement

waste reduction programming.

The grants should be available to schools on

a competitive basis and should be part of the

Nutrition Title.

In addition to authorizing a new grant program,

Congress should modify existing school grant

program selection processes to preference

applicants that have food waste reduction

programs. The USDA currently administers several

grant programs for schools, including the NSLP

Equipment Assistance Grants

122

and the Farm to

School Program (F2S).

123

Congress should require

the USDA to give priority to applications from

schools that include a food waste reduction or food

donation plan as part of their application. These

changes should be made through the Nutrition Title.

Lastly, Congress should mandate OVS across all

schools, for both NSLP and SBP, but preserve

some flexibility for schools to decline to use OVS

for the youngest grade levels if doing so is dicult

to implement or if it is deemed inappropriate for

the school population. It should further require the

USDA to publish additional guidance and implement

training for teachers and sta to adequately prepare

for the transition. These changes should be made

through the Nutrition Title.

Promote Food Education and

Food Waste Education in K-12

Programming

Annual potential to divert 14,800 tons of

food waste, reduce 70,200 metric tons

of CO

2

e, and save 3.45 billion gallons of

water, with a net financial benefit of $25.5

million

124

ISSUE OVERVIEW

There is a gap in school programming for food

waste education. While there are programs

8

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

providing grant funding to schools for food

and agriculture related education, including the

Food and Agriculture Services Learning Program

(FASLP), a program created in the 2014 Farm Bill

that provides funding for agriculture and nutrition

education in K-12 schools,

125

there is no required

focus on food waste. Additionally, the existing grant

programs for food education generally do not have

sucient funding to reach all interested schools and

thus are unable to maximize their positive impact.

Educating students on food waste can immediately

reduce food waste.

126

Educating students will also

realize long-term benefits because knowledge

gained in early education significantly impacts the

practices of individuals as they become participants

in the marketplace.

127

Schools can play an integral

part in educating future generations of consumers

and establishing sustainable food consumption

habits.

Congress should support eorts for schools

to educate students on food waste reduction

strategies. One program for which food waste

reduction education should be required is FASLP,

which should include a focus on food waste

reduction strategies in nutrition education, such as

portion size awareness, how to utilize surplus food,

composting, and correctly storing perishables.

128

Modifying the language around the FASLP in the

next farm bill to include food waste reduction

techniques will motivate schools to expand their

oerings, better account for food waste reduction,

and educate the next generation of consumers on

better food waste reduction practices.

Beyond food waste-specific education, Congress

should increase support generally for education

on food production and food systems to prevent

waste. One way to educate kids on food in schools

is through USDA’s Farm to School Program (F2S).

129

F2S combines food education with improved access

to local food by connecting schools with local

farmers.

130

By helping students develop a greater

appreciation for the origins of their food, this

program helps students, and in turn schools, waste

less.

131

Data from the 2013-2014 school year program

revealed that F2S resulted in a 17% reduction in

plate waste.

132

The USDA currently oers planning,

implementation, and training grants ranging from

$20,000 to $100,000 for F2S programs.

133

For the

2015-2016 school year, $120 million was requested

and approximately $25 million was awarded.

134

This data demonstrates large demand for F2S

programming, indicating that schools are interested

in these initiatives but lack sucient funding

for them. By increasing funding for F2S, which

has already been shown to reduce food waste in

schools, more schools will be able to participate in

the program and thus reduce their food waste.

IMPLEMENTATION OPPORTUNITY

The next farm bill should reauthorize

and modify the FASLP program’s

authorizing language in the Nutrition

Title to direct the USDA to award

extra points on grant applications

to schools that include food waste

reduction education as a focus in their program.

The next farm bill should reauthorize and increase

funding for the F2S program. This program has

been shown to eectively reduce waste in schools.

Increasing funding will allow additional schools to

participate.

135

This program was originally a part of

the Healthy, Hunger Free Kids Act of 2010,

136

but

could be included in the farm bill going forward

under the Nutrition Title.

Utilize Existing Federal

Household-level Food

Education Programs to

Increase Food Waste

Awareness

ISSUE OVERVIEW

On average, American households spend $1,866

per year on food that ends up going to waste.

137

According to the USDA Economic Research

Service (ERS), 10.5% of American households

faced food insecurity in 2020.

138

Many of these

families participate in food assistance programs

(e.g., Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program

for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC)), and have

limited budgets to spend on food. As discussed

above, individuals are often unaware of how much

food they waste and how to reduce their own food

waste at home.

139

There are multiple existing USDA

programs targeting those 13.8 million households

with food and nutrition education, yet currently

none of these programs are required to address

food waste.

With almost one-third of household food being

Opportunities to Reduce Food Waste in the2023 Farm Bill

9

wasted, education regarding strategies to reduce

food waste would inevitably save all consumers

money. Congress should promote national

food waste awareness by taking advantage of

existing food education programming to provide

educational materials to Americans about food

waste prevention. The authorizing language for the

Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program

(EFNEP) and for SNAP Education (SNAP-Ed) and

SNAP-Ed guidance documents should include

education related to increasing the eciency

of food usage or reducing food waste.

140

These

are existing programs and are therefore easy to

leverage, but additional eorts should be made by

the federal government to educate all consumers on

better food usage and reducing food waste.

EXPANDED FOOD AND NUTRITION EDUCATION

PROGRAM OPPORTUNITIES

EFNEP is a federally funded farm bill

141

grant

program that aims to enable low-income Americans

to “engage in nutritionally sound food purchasing

and preparation practices,” by providing funding

to land grant universities to deliver nutrition and

physical education programs in each state.

142

EFNEP

is funded annually through appropriations.

143

It

typically receives around $69 million per year.

144

While the program already provides educational

materials with strategies for shopping for healthy

food on a budget, the authorizing language should

also mention food waste reduction as a strategy

to support household food budgets. One of the

four stated core areas is increasing the ability of

participants to buy, prepare, and store nutritional

food.

145

This section of the program could mention

food waste reduction. It will be important to

make sure the education is culturally appropriate

and applicable to the situations of the recipients,

especially if many of them are depending on

providers like food banks, where recipients do not

typically get a choice in the foods they receive.

Education about food waste reduction could help to

extend the budgets of Americans, while helping to

address the nation’s food waste problem.

SNAP-ED OPPORTUNITIES

With over 42 million people receiving SNAP benefits

each year, SNAP-Ed represents an enormous

opportunity to educate individuals about food

waste and food waste prevention.

146

SNAP-Ed is

a federally funded grant program that seeks to

improve the likelihood that SNAP recipients will

make healthy food choices within a limited budget

and engage in physically active lifestyles consistent

with the current Dietary Guidelines for Americans

and the USDA food guidance.

147

SNAP-Ed was first

established in 1981 as “Nutrition Education” through

the Food Stamp Program and now receives funding

through annual appropriations bills—typically

receiving just over $400 million split between

the states.

148

Like EFNEP, SNAP-Ed focuses on

“promoting healthy eating and active lifestyles,”

while stipulating that program providers “must

consider the financial constraints of the SNAP-Ed

target population in their eorts.”

149

SNAP-Ed oers an opportunity to educate

Americans on how to best prevent food waste

while in no way diverting resources or attention

away from the primary objectives of the program—

improving nutrition outcomes. Some states,

including Maine and Connecticut, already include

food waste education within their SNAP-Ed

programming.

150

These states provide guidance on

how to reduce food waste and how to understand

date labels.

151

However, many states do not address

food waste in their programming, which represents

a tremendous missed opportunity. Rather than

leaving it to states to decide to include guidance

on reducing food waste, this instruction should

come from Congress through the farm bill. The 2014

Farm Bill amended SNAP-Ed to include education

on physical activity, which suggests that additional

goals can be included in the 2023 Farm Bill.

152

SNAP-Ed funding should be used to increase

awareness of food waste and share techniques to

reduce food waste—such as how to properly store

leftovers, how to use some ingredients that people

receiving food donations may be unfamiliar with,

and how to interpret date labels. Additionally, it

should be used to develop tools (for example, a

meal planning tool) to help participants prevent

food waste. Such a tool could be developed out

of existing information and tips on meal planning

available through multiple states’ SNAP-Ed