1750 Massachusetts Avenue, NW | Washington, DC 20036-1903 USA | +1.202.328.9000 | www.piie.com

WORKING PAPER

24-2 Trade policy, industrial policy,

and the economic security of

the European Union

Chad P. Bown

January 2024

ABSTRACT

Out of fear about its economic security, the European Union is transitioning to a

new form of international economic and policy engagement. This paper explores

some of the major trade issues surrounding the bloc’s economic security, the role

of trade and industrial policy in achieving its objectives, and some of the economic

costs of doing so. It begins by explaining why economic security is suddenly playing

such a prominent role and providing early evidence to motivate these government

interventions. It then turns to a case study—new policies associated with China’s

exports of electric vehicles and graphite—that highlights the difficult choices and

practical challenges the European Union faces in tailoring policy to address concerns

over economic security. The paper then introduces the domestic policy instruments

that the European Union, its member states, and other governments are pursuing

to address economic security, including stockpiling and inventory management,

investment or production subsidies, tariffs, export controls, and regulations on

foreign investment, as well as the scope for selective international cooperation over

such policy instruments. The paper concludes with some caveats about abandoning

interdependence and lessons from history.

JEL codes: F13, L52

Keywords: Economic security, supply chains, industrial policy, trade policy, tariffs,

subsidies, export controls

Author’s Note: A revised version of this paper is forthcoming in an ITCEI Report by

CEPR. For helpful conversations and feedback, the author thanks Panle Jia Barwick,

Olivier Blanchard, Heather Grabbe, Gene Grossman, Wonhyk Lim, Niclas Poitiers, Michele

Ruta, Reinhilde Veugelers, Beatrice Weber, Jeromin Zettelmeyer, and participants at the

CEPR Paris Symposium 2023. Thanks to Jing Yan for outstanding research assistance;

Nia Kitchin and Alex Martin for assistance with graphics; and Barbara Karni and Madona

Devasahayam for editorial assistance.

Chad P. Bown is the

Reginald Jones Senior

Fellow at the Peterson

Institute for International

Economics.

2 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

“This is why—after de-risking through diplomacy—the second strand of our

future China strategy must be economic de-risking. The starting point for this is

having a clear-eyed picture on what the risks are.”

—Ursula von der Leyen, President of the European Commission,

March 30, 2023

1. INTRODUCTION

Out of fear about its economic security, the European Union is transitioning

to a new form of international economic and policy engagement. The Trump

administration in the United States, Russia’s invasion of and war on Ukraine, and

concerns over China’s increasingly aggressive foreign and economic policies have

combined to put a new EU policy into motion. Without the assurance that other

countries will continue to follow the rules of a multilateral trading system, the

European Union is working through what comes next.

1

It is taking steps to rebalance its position in the global economy. While

seeking to preserve the benefits of interdependence with the rest of the world,

the European Union is contemplating policies that would induce change. One

change seeks to alter the footprint of global production for certain goods,

affecting whom it sources imports from and whom it sells exports to. It wants to

decrease certain trade dependencies (which could be weaponized) and increase

others (to encourage diversification). A second change is the enactment of new

contingent policy instruments intended to allow the European Union to respond

more quickly when policymakers in other countries act badly (or to establish a

credible threat sufficient to deter them from doing so in the first place).

This paper describes how the European Union is seeking to use trade and

industrial policy to achieve its economic security objectives. It identifies some

of the economic costs and tradeoffs of using such policies. Because the issues

it examines—many of which are noneconomic, for which reasonable estimates

of costs and benefits are lacking—are evolving, the paper shies away from

normative recommendations. Instead, it explores the political economy of what

is emerging and why. The paper focuses on EU efforts to “de-risk” vis-à-vis China

especially, given the emphasis EU policymakers now place on doing so.

The paper is organized as follows. Section 2 defines the concept of economic

security and the events that led it to play such a sudden and prominent

role in modern policy.

2

It provides some early evidence to motivate the new

policy interventions but emphasizes that much remains unknown, especially

concerning their design.

Section 3 explores a case study that highlights the difficult choices the

European Union faces in responding to threats to its economic security. The

case study involves the electric vehicle (EV) industry, the European Union’s

potential use of trade defense instruments (TDIs) to address unfairly subsidized

1 See European Commission (2023a).

2 Other treatments touching on some of the aspects of economic security introduced here

include Hoekman, Mavroidis, and Nelson (2023) and Pinchis-Paulsen, Saggi, and Mavroidis

(forthcoming). Paulsen (2023) presents a legal treatment from the perspective of historical

trade negotiations.

3 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

imports from China, and China’s potential retaliatory response of placing export

restrictions on graphite, a critical material needed to manufacture EV batteries.

It also identifies unknowns facing policymakers seeking “a clear-eyed picture on

what the risks are,” in the words of European Commission President Ursula von

der Leyen. The section also explores empirically whether the European Union’s

trade interdependence with China may be deepening—despite stated goals

to de-risk—in part because of the third-country effects arising from the US–

China trade war.

Section 4 introduces the policy instruments the European Union, its member

states, and other governments are pursuing to address concerns about their

economic security. They include stockpiling and inventory management,

investment or production subsidies, various forms of tariffs, export controls, and

regulations on foreign investment. This section also highlights proposals for new

policy instruments, analyzes the associated tradeoffs, and briefly describes basic

World Trade Organization (WTO) rules that might discipline such instruments.

Section 5 turns to the potential for selective international cooperation over

the use of such policy instruments. It explores how countries facing common

concerns over economic security have been acting in coordinated fashion—

implicitly or explicitly—and the difficulties of doing so.

Section 6 concludes with some caveats and lessons from history.

2. THE MODERN POLICYMAKER CONCERN OVER ECONOMIC SECURITY

2.1 What is economic security?

Economic security at the national level is still an emerging concept.

3

At a

minimum, it involves a country getting the goods and services it needs when it

needs them, at a reasonable price, with an acknowledgment that its economy is

open and has some interdependence with the outside world. The nascent field

of economic security shares similarities with national security, which Murphy and

Topel (2013, 508) define as “the set of public policies that protect the safety

or welfare of a nation’s citizens from substantial threats.”

4

Modern concerns

over economic security, however, involve recognition that others—typically

policymakers abroad—may be working against a country’s effort to achieve

its objectives.

Policymakers might work at cross-purposes to another country’s interests for

a variety of reasons, economic and noneconomic. For example, a large (price-

shifting) exporting country might impose export restrictions or a nationally

optimal export tax in order to shift the terms of trade in their country’s favor

if the national benefits of the price change are larger than the efficiency costs

3 In the poverty literature, economic insecurity at the individual level is relatively well defined,

with a variety of measures and data informing policymakers on economic well-being.

4 On national security (NS), Murphy and Topel (2013, 508) write, “While NS policies are typically

thought of in terms of military assets, our definition includes the development and deployment

of any public good that would mitigate catastrophic outcomes for a large segment of the

population.”

4 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

associated with the economic distortions it causes.

5

Domestic policymakers

might give in to political pressure to impose a policy that benefits one local

group (consumers) at the expense of another (firms/exporters); if the country is

large, the policy could have unintended effects abroad.

6

Foreign policymakers

could also be concerned about the relative sizes of two economies—which affect

the ability to wage war—and therefore want to slow the other country’s economic

growth. They might be seeking to achieve a more targeted, albeit noneconomic

objective (i.e., curtailing another country’s access to a good or service that

improves its military capabilities and threatens the other country’s national

security). Or they could be seeking to influence political outcomes abroad toward

a leader more sympathetic to their country’s interests.

This concept of economic security expands the scope of the nascent

literature on supply chain resilience, which examines other important shocks—

climate change, public health emergencies, natural disasters—that could be

transmitted from one country to another through interdependent supply chains.

By including resilience to actions by malicious policymakers abroad, economic

security also recognizes that foreign governments may adopt noncooperative

policies and that a strategic setting is in play.

7

The European Commission, some EU member states, the US government,

and academics have begun to develop criteria to help policymakers. The initial

approach involved efforts to define an ex ante basket of goods and services

that are necessary for economic security and for which countries have import

dependencies that might be vulnerable.

8

Mejean and Rousseaux (forthcoming), for example, use detailed trade

data to build on the European Commission’s “bottom-up” approach to assess

EU vulnerabilities.

9

To the extent possible, they also include information on

the European Union’s domestic supply capabilities, in order to assess the

ability of EU consumers to substitute away from imports if necessary toward

domestic production. They propose refinements to earlier lists of potentially

vulnerable products by also considering the type of risk government policy

is supposed to address. For example, policymakers might be more worried

about the vulnerabilities of products that are essential for human health and

have public good qualities, such as personal protective equipment (PPE) and

vaccines, than they are about products for which the main concern is economic

competitiveness.

5 This dimension is not the only one along which interdependence could be exploited. A

large importing country could impose tariffs. A country with large state-owned enterprises

could allocate its foreign direct investment flows in ways that benefit them. On the role of

international trade agreements such as the WTO in handling the international externalities

associated with policy changes, see Bagwell and Staiger (1999, 2002).

6 India, for example, periodically imposes export restrictions on onions, in order to limit domestic

price increases for a staple food. It responded to the sudden surge in domestic COVID-19

infections in 2021 by banning exports of COVID-19 vaccines from the Serum Institute for six

months (Bown and Bollyky 2022).

7 Even if markets are competitive for firms, countries may still be “large,” in that governments

can use border policies (import or export restrictions) to exert market power by influencing

the terms of trade and thus act strategically vis-à-vis actors in other countries.

8 See European Commission (2020, 2021); White House (2021); Bonneau and Nakaa (2020); and

Jaravel and Mejean (2021).

9 See also Baur and Flach (2022) and Vicard and Wibaux (2023).

5 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Such trade dependency approaches have their limitations, however, because

of deficiencies in the data available to policymakers. For example, information

on the foreign source of imports may be available at a detailed (product) level,

but the same level of aggregation is not typically available for foreign production

or for input–output relationships involving foreign supply chains. (The graphite

example presented below is one illustration of this potential limitation.) The

European Union can be exposed indirectly: A disruption in country B can hurt

EU imports from country A because A is dependent on imported inputs from

B. Policymakers may not be able to observe this dependency, because it arises

through input choices made by firms in country A in order to sell a good or

service to the European Union.

10

Policymakers also need more information about the responsiveness time

horizon. Beyond whether and how costly it is for EU consumers to find an

alternative production source, policymakers want to know how quickly such a

switch can materialize. This issue has taken on increased salience since product

shortages developed during the pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

11

A final

open question involves whether dependencies have the potential to shift more

quickly and with less warning (to outsiders) when a major trading partner is a

state-centric nonmarket economy. Is trade dependency on China, for example,

riskier than dependency on some other country because China is more likely to

use industrial policy and to do so through opaque means that make such shifts

difficult for outsiders to observe and respond to?

2.2 How did we get here?

Three main factors explain why economic security suddenly became such a

concern for policymakers: the success of the international trading system at

achieving some outcomes, its failure at achieving others, and the suddenly

changing world.

For decades, major industrial economies like the European Union and United

States largely got what they wanted out of the global system. Following the end

of World War II, they repeatedly gathered to negotiate reciprocal reductions

to tariff barriers. Low trade barriers combined with major technological

advancements (containerized shipping, the information and communications

technology [ICT] revolution, and managerial improvements) and peace after

the end of the Cold War (and China’s 1978 opening up) resulted in efficient and

often global supply chains. However, this efficiency also sometimes resulted in

the geographic concentration of production for certain goods and services that

these economies would come to regret once the world changed.

The global trading system failed elsewhere. China’s integration into the

global economy was phenomenally successful at lifting hundreds of millions

of its people out of poverty in less than four decades. But its integration was

also disruptive to people elsewhere, for reasons beyond the mere entrance of a

new trading partner forcing incumbent economies to adjust. China’s failure to

10 For an application to US supply chain exposure to China, see Baldwin, Freeman, and

Theodorakopoulos (forthcoming).

11 For an examination of the average duration of firm-to-firm purchasing relationships as a proxy

for responsiveness to shocks, see Martin et al. (forthcoming).

6 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

transition to a market economy, its use of industrial policy, its deployment of

export restrictions and targeted acts of economic coercion, and the inability of

trading partners to turn to the WTO to do much about it led US political leaders

in particular to perceive that the WTO system had failed. There would be no

quick fixes, as a design flaw meant that the WTO lacked a legislative function to

change its rules in ways that would allow the system to keep going. A result was

the US–China trade war, in which both countries violated WTO rules and norms,

and the withdrawal of US support of binding WTO dispute settlement.

12

The third factor explaining the new emphasis on economic security is the

suddenly changed world. The distribution of political-economic shocks has

changed in ways that challenge the optimality of the existing location of global

production. For certain goods, manufacturing has been deemed excessively

concentrated geographically. Climate change has increased the frequency and

severity of storms and droughts, leading to extreme events ranging from floods

to wildfires. The COVID-19 pandemic woke the world up to the frightening

possibility of sudden public health emergencies that could lead to lockdowns

affecting production, snarled transportation and logistics, and wild swings in

demand. These shocks raised concerns about supply chain resilience, which are

arguably more economic (than geopolitical) in nature.

Geopolitics is the last important change to the distribution of shocks; it is

also the factor that differentiates economic security from simple supply chain

resilience.

13

Geopolitics means that a foreign policymaker may actively work to

reduce the economic security of another economy. From the European Union’s

perspective, three major changes to geopolitics are worth highlighting.

The first was the shock over the presidency of Donald J. Trump. Trump bullied

the European Union, supported Brexit, and sought to undermine European

institutions.

14

By threatening to withdraw the United States from NATO, he

put decades of European military security at risk.

15

On trade policy, he ended

up imposing tariffs only on European steel and aluminum, an action not that

different in terms of its economic magnitudes from what the George W. Bush

administration did in 2002. However, the US relationship with Europe soured

when he claimed that those metal imports from the European Union threatened

America’s national security and when he further threatened additional tariffs on

imports of European cars. His administration ended US support for the WTO,

a problematic step given that the multilateral system forms the institutional

foundation for the European Union’s trade relationship with the world. Then,

under Trump’s 2020 Phase One agreement, China was supposed to purchase

additional US exports, even if they came at the expense of exports from

Europe and other countries.

16

(These purchases never happened, as described

12 On the US–China trade war, see Bown (2021). On the United States and WTO dispute

settlement, see Bown and Keynes (2020).

13 For one formal modeling approach, see Clayton, Maggiori, and Schreger (2023).

14 See Matthew Rosenberg, Jeremy W. Peters, and Stephen Castle, “In Brexit, Trump Finds a

British Reflection of His Own Political Rise,” New York Times, July 13, 2018.

15 Julian E. Barnes and Helene Cooper, “Trump Discussed Pulling US From NATO, Aides Say amid

New Concerns over Russia,” New York Times, January 14, 2019.

16 See Chad P. Bown, Unappreciated Hazards of the US–China Phase One Deal, PIIE Trade and

Investment Policy Watch, January 21, 2020.

7 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

below.) The election of Joseph R. Biden restored many—though not all—of the

pre-Trumpian features of the transatlantic alliance, but the fear of a return by

President Trump in 2024 never receded from European view.

17

The second and most important geopolitical event for Europe was Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine. The move exacerbated Russia’s deteriorating relationship

with Europe and other Western economies, which began to sour following

Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea. In 2022, Russia weaponized its exports by

withholding sales of natural gas to Europe through the Nord Stream 1 pipeline.

Prices spiked, contributing to inflation, stoking political problems across Europe,

and causing immediate-term economic concerns for the competitiveness of

energy-intensive industries, especially in Germany.

Europe’s third geopolitical concern involves China. Under President Xi

Jinping, China has become much more aggressive toward its neighbors,

threatening the security of major shipping lanes through the East and South

China Seas. It has widened its use of economic coercion by cutting off trade to

punish countries whose foreign policy it disagrees with, including Lithuania for its

diplomatic ties with Taiwan and its opening a “Taiwan Representative Office” in

Vilnius.

18

(There is also increasing worry that China may seek to retake Taiwan by

force.) Finally, in response to EU sanctions over human rights violations related

to the mass detention and persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang, China imposed

counter sanctions, including on members of the European Parliament.

2.3 Is a policy needed, or are firms adjusting on their own?

An important motivating question is whether policy is needed. Perhaps these

shocks are not systematically affecting economic activity or firms are already

internalizing the fact that the world is changing and adjusting their decisions

even in the absence of new government policy.

There is evidence that some of these shocks have adversely affected firms

and supply chains. While many of the shocks are new and have therefore not yet

been fully examined, the evidence to date is that shocks have had the expected

impacts. Consider, for example, the earthquake that led to the tsunami and

nuclear incident at Fukushima, Japan in 2011. Boehm, Flaaen, and Pandalai-

Nayar (2019) find that the decline in US manufacturing output resulting from

Japanese affiliates that were unable to import because of the shock was sizable.

Lafrogne-Joussier, Martin, and Mejean (2023) study the behavior of French firms

in response to the early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns in China. They find that

French firms sourcing inputs from China saw imports fall by more than firms

sourcing from elsewhere and that those firms subsequently experienced a larger

drop in domestic sales and exports. In terms of mitigation strategies, geographic

diversification did not appear to help, but firms with larger inventories did seem

to weather the shocks better than other firms did.

17 See Andrew Gray and Charlotte Van Campenhout, “Trump Told EU That Us Would Never Help

Europe under Attack: EU Official,” Reuters, January 10, 2024.

18 The Chinese government views Taiwan as part of China and that the island should not have

independent diplomatic relations with other countries. On the Lithuania incident, see Norihiko

Shirouzu and Andrius Sytas, “China downgrades diplomatic ties with Lithuania over Taiwan,”

Reuters, November 21, 2021.

8 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Early evidence about firms’ response to incentives about resilience is mixed.

Castro-Vincenzi (2022), for example, examines how the global automobile

industry adjusted to climate-related shocks. He finds that firms responded to the

increased incidence of extreme weather events (floods) by having more plants,

operating smaller plants, and holding some unused capacity at those plants,

in order to be able to smooth their global production over bad states of the

world. Khanna, Morales, and Pandalai-Nayar (2022) examine firms exposed to

the sudden shock of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns in India. They find that firms

and their supply chains were adversely affected in the expected ways, but they

fail to find evidence that firms with more complex supply chains underperformed

those with simpler supply chains. One interpretation of this evidence is that firms

that know that they have complicated production chains invest in resilience ex

ante to mitigate shocks. However, in examining firms’ long-run response to the

Fukushima incident, Freund et al. (2022) find no evidence that they re-shored or

nearshored production or increased import diversification to mitigate risk. This

finding suggests that active policies may be needed to induce firms to diversify.

Even for the firms that may be responding to the heightened likelihood of

shocks by increasing their supply chain resilience, are they investing optimally

in resilience and, by extension, in security? Are they doing enough? Might

some be investing too much? New theoretical work has begun to explore the

market failures and externalities that might exist as well as the appropriate

policy intervention to create the right incentives. So far, this work suggests that

the answer is complex, nuanced, and highly dependent on the details of the

underlying supply chain and network.

19

Nevertheless, the European Union and

other countries are already changing policies, even if they are not being guided

by this research. The following sections explain how.

3. EUROPE’S TOUGH CHOICES INVOLVING ECONOMIC SECURITY

The European Union faces important choices and difficult tradeoffs. Its “open

strategic autonomy” approach suggests a wish to remain internationally

integrated with the outside world.

20

Although interdependence failed to prevent

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, most of the evidence from the post–World War II

process of European integration is that it can be an important force for policy

moderation and peace. Although its perspective on China has become more

jaded, Europe does not see eye to eye with Washington. The differing views

partly reflect the fact that, unlike the United States, Europe is not bound by

treaty to uphold the military security of countries in Asia and the Pacific.

21

But

European positioning toward China also represents a hedge, as the bloc’s own

19 See Grossman, Helpman, and Lhuillier (forthcoming) and Grossman, Helpman, and Sabal

(2023).

20 European Commission Director General for Trade, Sabine Weyand, defined open strategic

autonomy as meaning “we act together with others, multilaterally, or bilaterally, wherever we

can. And we act autonomously wherever we must. And the whole of it adds up to the EU

standing up for its values and interests” (Bown and Keynes 2021a).

21 See Lindsey W. Ford and James Goldgeier, “Who Are America’s Allies and Are They

Paying Their Fair Share of Defense?” Brookings Commentary, December 17, 2019; US State

Department, “US Collective Defense Arrangements,” Archived Content, 2009–17.

9 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

future relationship with the United States remains uncertain over fear of the

reelection of Trump, who has already proposed imposing a 10 percent tariff on all

imports, including imports from Europe.

22

At the same time, the European Union is facing increasing threats to its

economic security from China. This section illustrates them by examining

ongoing EU–China disputes over EVs, critical minerals, and materials needed to

manufacture batteries. It then explores the data, which, paradoxically, suggest

that not only is this case study not unique but that some of Europe’s trade may

be becoming more rather than less dependent on China, for reasons outside of

the control of European policymakers.

3.1 Is China weaponizing supplies and exports of electric vehicles, graphite

and critical minerals?

China has actively used industrial policy in a number of sectors, including its EV

supply chain.

23

One key element was a local content requirement for EV batteries,

introduced in 2016 and kept in place until 2019.

24

During this period, China’s

EV consumer subsidies were limited to automakers that used batteries on the

government’s “whitelist,” which included only local Chinese firms like BYD and

CATL, hurting Japanese and Korean battery manufacturers in particular.

Barwick et al. (in progress) provide evidence that as expected, China’s

discriminatory policy for EV batteries led to an increase in battery sales by BYD

and CATL. They also find, however, that because of learning-by-doing in the

downstream EV industry, China’s whitelist policy combined with EV consumer

subsidies (applied around the world) resulted in sharper EV price reductions

for vehicles using BYD and CATL batteries. The implication is that China’s

discriminatory local content policy for EV batteries indirectly provided downstream

Chinese EV manufacturers a further unfair advantage that worked like a subsidy.

25

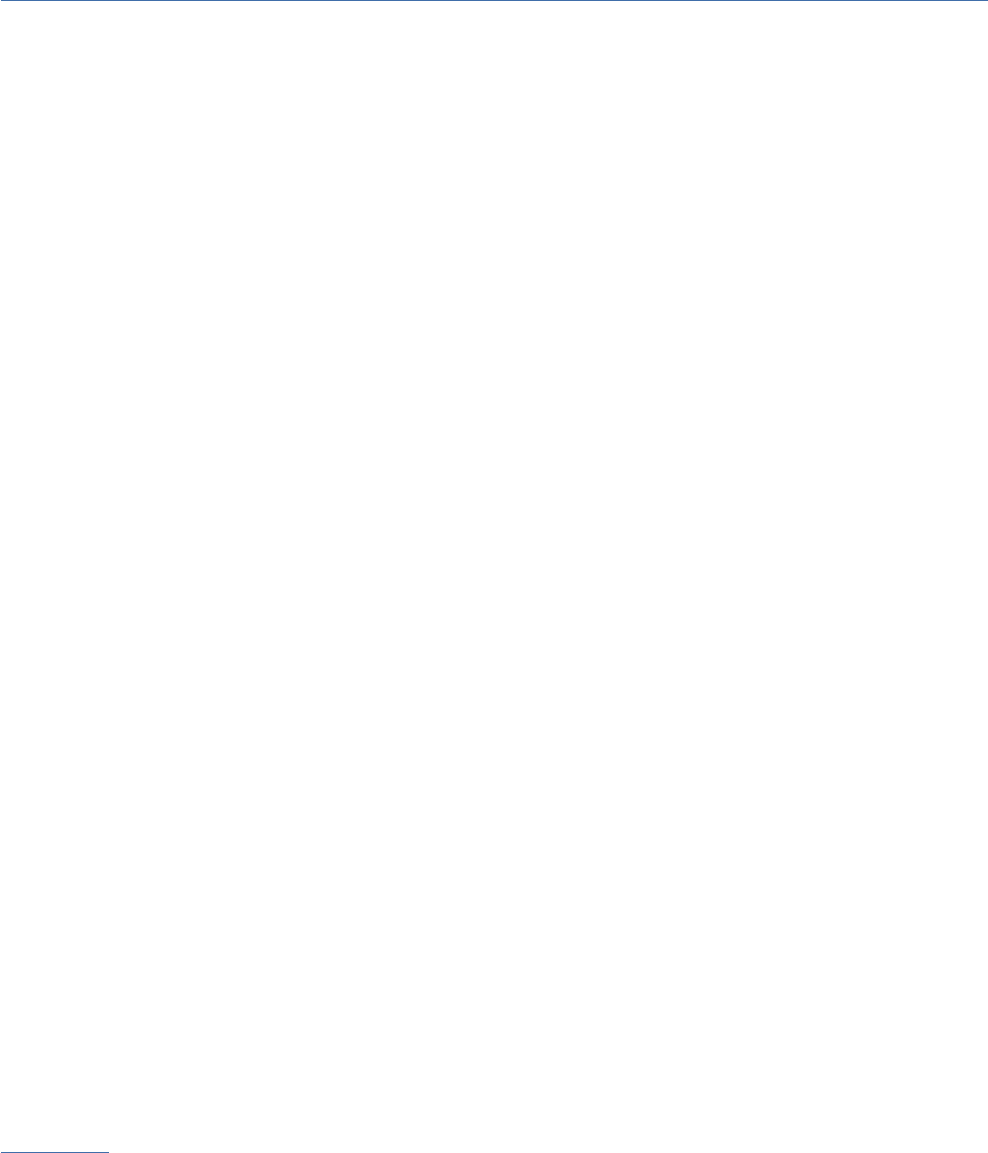

China’s subsidies and industrial policy are likely contributors to the surge in

China’s EV exports into the European Union (figure 1). China’s industrial policy in

other sectors has proven concerning: In addition to the injury it caused to firms

in other markets, the subsidies can result in excessive firm entry, with inefficient

companies operating at insufficient scale. The current worry is that China’s

industrial policy for EVs will similarly result in excess capacity and the dumping

of its exports, including into the nascent European EV market.

26

22 See Jeff Stein, “Trump Vows Massive New Tariffs If Elected, Risking Global Economic War,”

Washington Post, August 22, 2023; Charlie Savage, Jonathan Swan, and Maggie Haberman,

“A New Tax on Imports and a Split from China: Trump’s 2025 Trade Agenda,” New York Times,

December 26, 2023.

23 China’s industrial policy for the EV supply chain follows a pattern that is similar to that in

industries such as shipbuilding, steel, aluminum, and solar panels. For new techniques to

identify, measure, and assess the impact of China’s industrial policy on shipbuilding, see

Kalouptsidis (2018) and Barwick, Kalouptsidi, and Zahur (forthcoming).

24 Qichao Hu, “In Honor of John B. Goodenough’s 100th birthday: What America Can Learn from

China’s Success in EV Batteries,” SES, July 22, 2022.

25 Barwick et al. (in progress) find that China’s industrial policy reduced EV sales globally relative

to a counterfactual without the whitelist policy. The intuition is that the Chinese policy shifted

sales from previously low-cost to high-cost suppliers, allowing inefficient firms to expand,

resulting in business-stealing from more efficient firms.

26 Joe Leahy, “EU Companies Warn China on EV Overcapacity,” Financial Times, September 19,

2023.

10 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Figure 1

Chinese exports of electric vehicles to the European Union have skyrocketed,

leading to an EU anti-subsidy investigation

ROW = rest of world; EV = electric vehicle

Source: Compiled by the author with data from UN ITC Trade Map and Chinese customs.

In October 2023, the European Commission announced an anti-subsidy

investigation into Chinese EVs that could result in countervailing measures

(tariffs).

27

The case faced a mixed response across Europe. The French

government welcomed the investigation,

28

in part because automakers like

Renault and Peugeot are direct competitors of lower-priced Chinese EV brands

like BYD and Polestar. Germany, whose automakers export some EVs from their

Chinese factories back to Europe, has been more circumspect,

29

concerned

about being caught up in the EU tariffs.

30

It is also worried about the potential

of Chinese retaliation through tariffs that could hit exports into China from

Germany’s European plants (more on this below) or that might go after the

German industry’s sizable investment in facilities in China.

China immediately responded to the European Commission’s investigation by

announcing new export restrictions on graphite (on “national security” grounds).

31

27 European Commission, “Commission Launches Investigation on Subsidised Electric Cars from

China,” Press release, October 4, 2023.

28 Reuters, “France’s Le Maire Welcomes EU Action against Chinese-Made Electric Cars,”

September 13, 2023.

29 Patricia Nilsson, Gloria Li, and Sarah White, “German Carmakers in the Line of Fire of Possible

EU–China Trade War,” Financial Times, September 19, 2023.

30 Siyi Mi, “EU Needs More Than Just Tariffs to Counter China’s Electric Cars,” Bloomberg,

September 28, 2023.

31 China’s Ministry of Commerce, “Announcement of the Ministry of Commerce and the General

Administration of Customs on Optimizing and Adjusting Temporary Export Control Measures

for Graphite Items,” October 20, 2023. China’s export curbs also likely target the United

States, Japan, South Korea, and other countries. They follow on new Chinese export curbs

on germanium and gallium, announced immediately after the Netherlands imposed export

controls on semiconductor manufacturing equipment, following the US lead (Qianer Liu and

Tim Bradshaw, “China Imposes Export Curbs on Chipmaking Metals,” Financial Times, July 3,

2023).

11 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

It was not the first time China retaliated against an EU TDI, although in the past

it retaliated by imposing its own TDIs, as it did in response to EU measures on

steel fasteners (Bown and Mavroidis 2013) and X-ray equipment (Moore and Wu

2015); in response to EU measures on solar panels, China retaliated with a TDI

on upstream polysilicon.

32

(In January 2024, China did also respond to France’s

support for the Commission’s EV investigation with a new TDI action potentially

affecting French cognac.

33

)

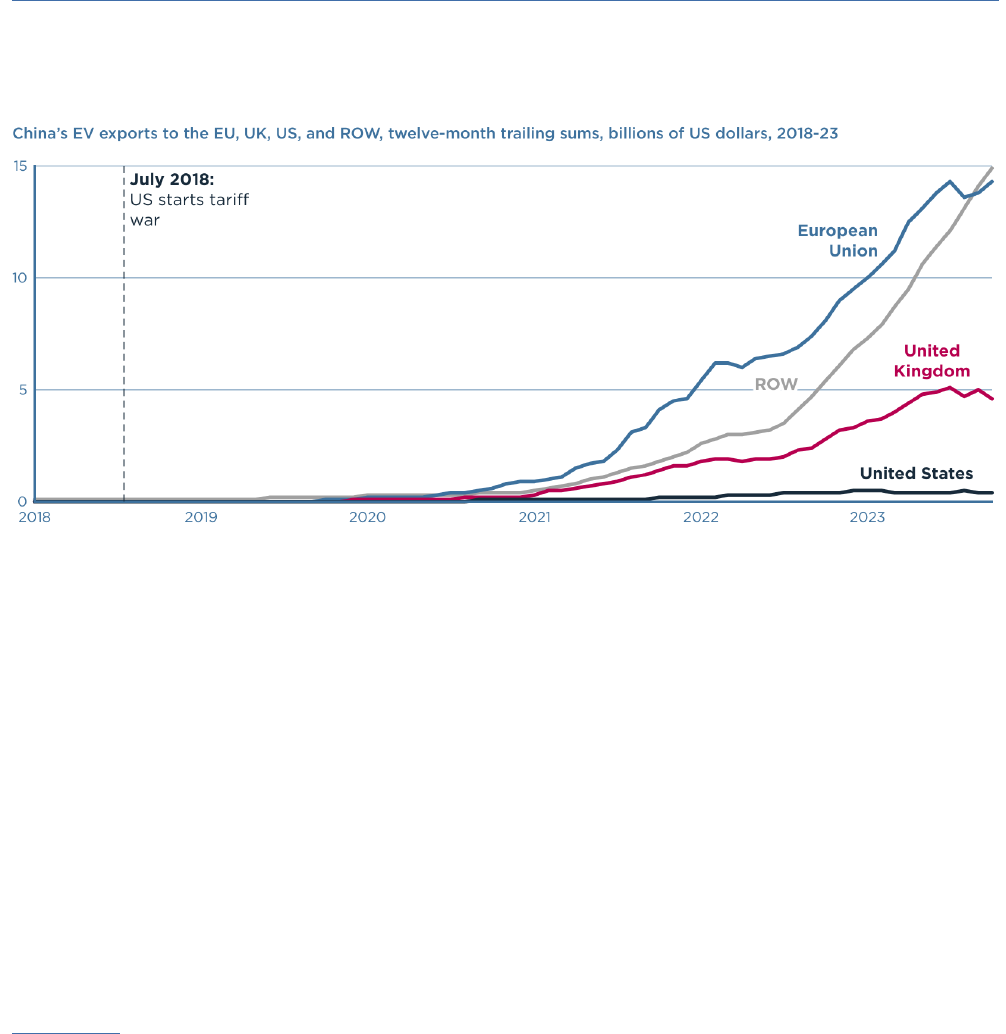

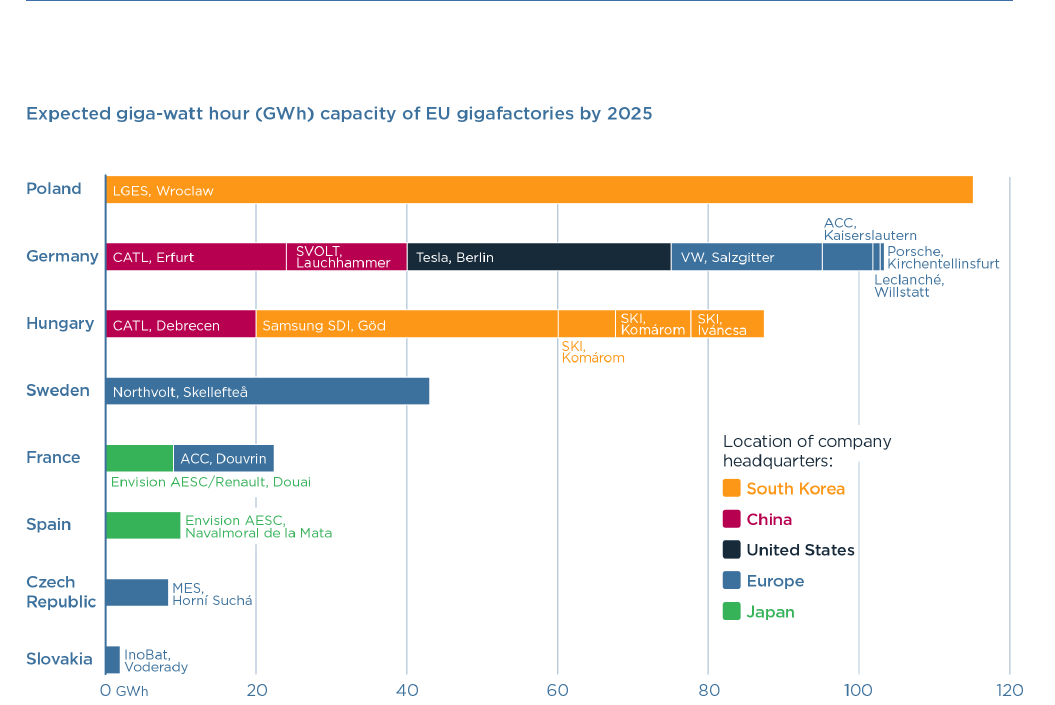

Graphite is used to produce EV batteries. The European Union is the largest

importer of Chinese graphite subject to the new export restrictions (figure 2).

The three largest EU member state buyers of Chinese graphite exports are

Poland, Hungary, and Germany, home to some of the European Union’s largest

EV battery plants (figure 3). Chinese battery plants are coming online in Hungary

and Germany; other EV battery plants across the European Union are operated

by firms from Korea (Samsung SDI, SK Innovation, and LG Energy Solutions);

Japan (AESC); the United States (Tesla); and a host of European countries.

34

Figure 2

EU member states are large buyers of the Chinese graphite that China

suddenly announced would be subjected to export controls

Notes: HS codes 38011000; 38019090; 68151900; 25041010; 25041091; 38019010; 38249999. China’s

exports to rest of world were $1.4 billion (not shown).

Source: Compiled by the author with data from Chinese customs.

32 Michael Martina, “China Hits EU with Final Duties on Polysilicon,” Reuters, April 30, 2014.

33 Edward White, Adrienne Klasa, and Madeleine Speed, “China Targets French Brandy Imports in

Escalating Trade Dispute,” Financial Times, January 5, 2024.

34 Edward White, William Langley, and Harry Dempsey, “China Imposes Export Curbs on

Graphite,” Financial Times, October 20, 2023; Tom Philips, “Top Five: EV Battery Factories in

Europe,” Automotive IQ, April 21, 2020; Marton Dunai, Yuan Yang, and Patricia Nilsson, “The

Electric Vehicle Boom in a Quiet Hungarian Town,” Financial Times, November 29, 2022.

12 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Figure 3

Chinese battery manufacturers in Europe are clustered in Germany and Hungary

LGES - LG Energy Solutions; CATL = Contemporary Amperex Technology Co., Limited; SKI = SK Innovation;

VW = Volkswagen; AESC = Automotive Energy Supply Corporation; ACC = Automotive Cells Company; MES

= Magna Energy Storage

Notes: Announcements as of January 2024.

Source: Compiled by the author with data from Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

What worries EU policymakers is how China chooses to implement these

graphite export restrictions. It could cut off all buyers located in Europe, harming

the EU battery industry and, by extension, EV manufacturing plants in Europe,

beyond the injury already inflicted by China’s subsidies and industrial policy for

batteries and EVs. Alternatively, China could allocate graphite export licenses

in a manner that differentiates between buyers within Europe. One approach

would be to allocate licenses in a way that drives a political wedge between

EU member states, in order to influence the outcome of Brussels’ anti-subsidy

investigation. Another would be to allocate licenses to benefit battery plants of

Chinese-headquartered firms in Europe, such as CATL, at the expense of non-

Chinese battery manufacturers in Europe. This strategy could have similar effects

as the 2016–19 whitelist policy, raising the question of whether China’s application

of differential export restrictions—which can work like a subsidy economically—

satisfies the legal definition of a subsidy and therefore justifies EU use of its new

Foreign Subsidies Regulation, discussed below.

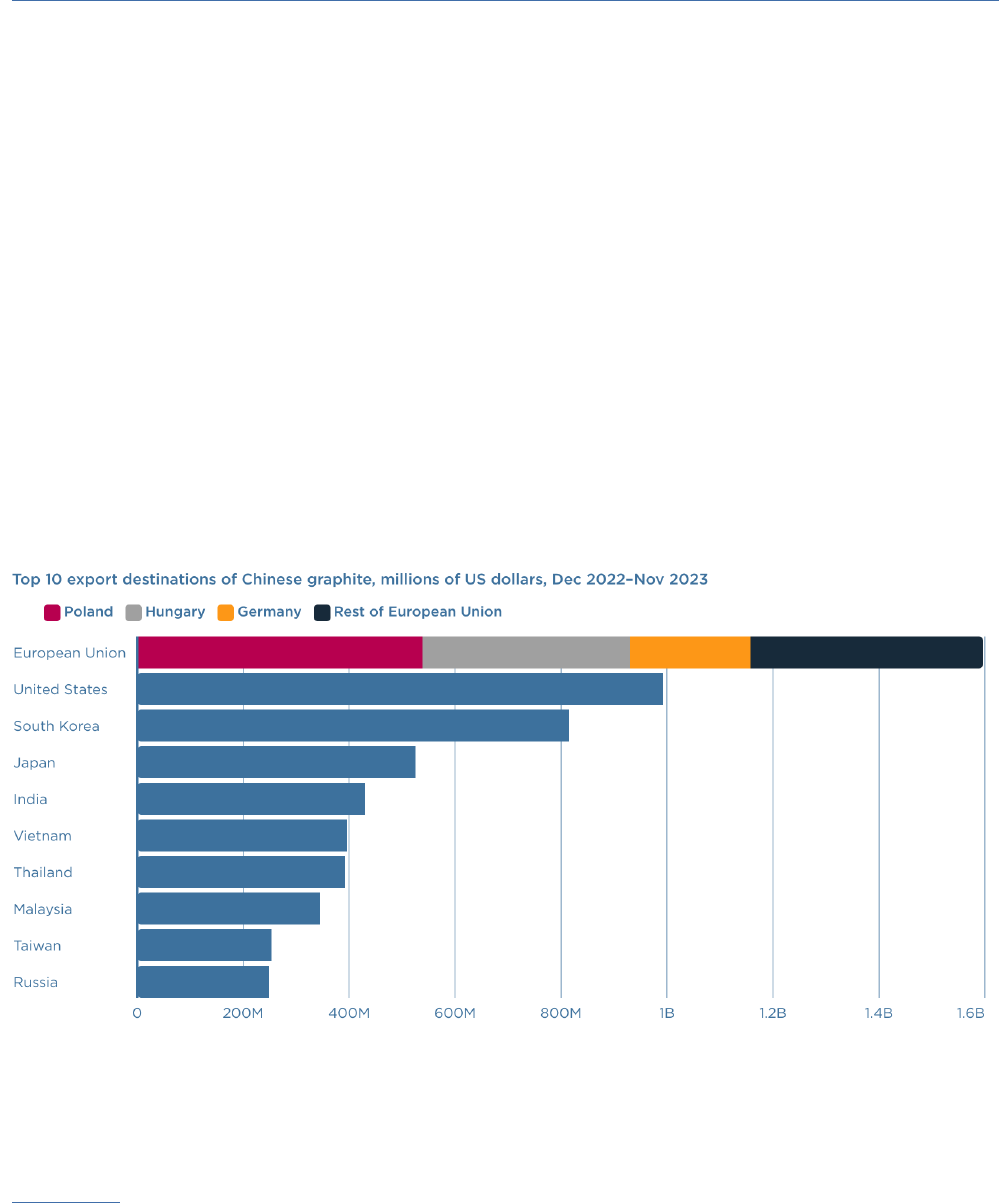

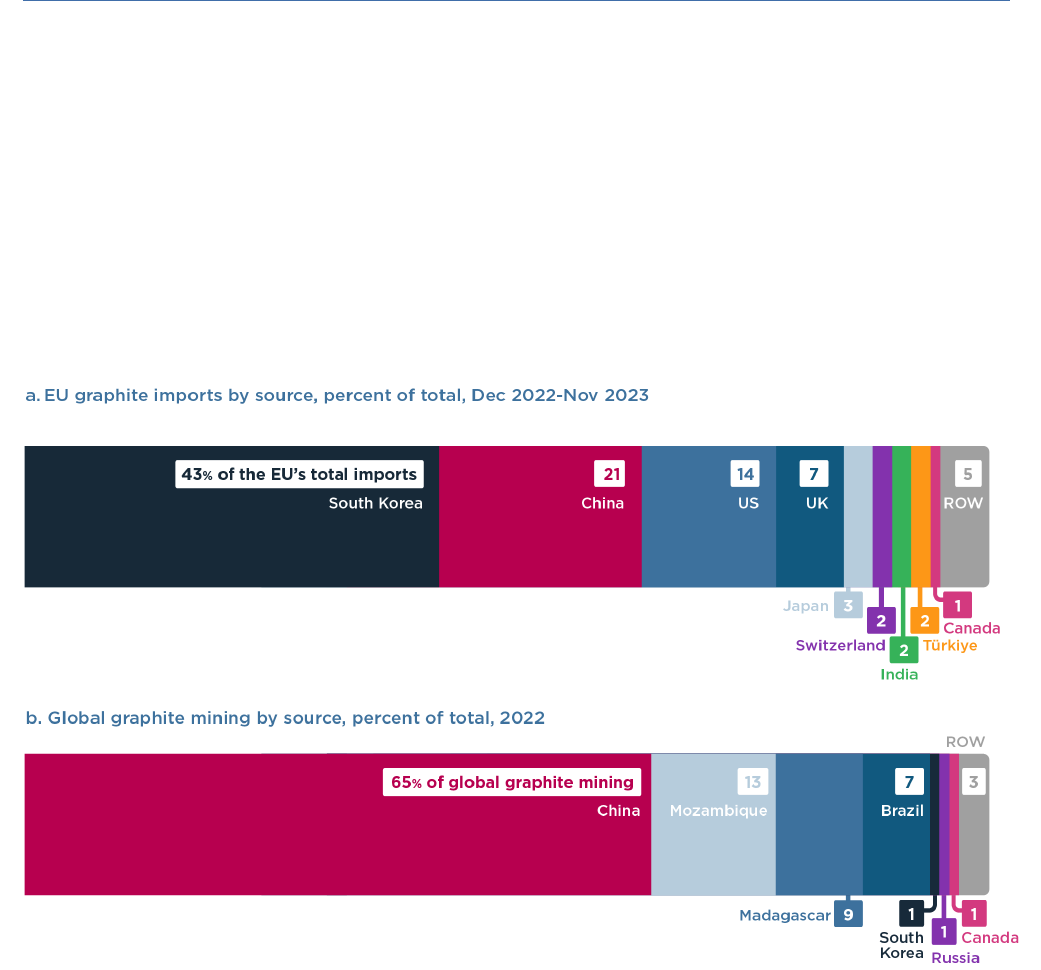

The graphite example also helps illustrate the separate informational challenge

facing “clear-eyed” policymakers seeking to de-risk from China. Suppose forward-

looking EU policymakers examined the data to assess whether they should be

13 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

concerned about excessive dependence on graphite imports from China. Panel

a of figure 4 displays the most disaggregated trade data comparable across

countries (the six-digit Harmonized System level) for the graphite products over

which China ultimately imposed export restrictions. Viewing it alone, they might

have concluded that the European Union had little to worry about, as China is

the source of less than 25 percent of EU graphite imports; South Korea is a larger

foreign source than China, and other trustworthy trading partners, including the

United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan, also export graphite.

Figure 4

The EU’s apparent low import dependence on Chinese graphite may be

misleading given China’s domination of upstream mining

ROW = rest of world

Notes: Total may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Sources: Panel a: Compiled by the author with data from Eurostat for the 12 months of December 2022–

November 2023, 6-digit HS codes 380110; 38019; 681519; 250410; 380190; 382499. Panel b: Compiled

by the author with 2022 data from USGS, Graphite Statistics and Information, Mineral Commodity

Summaries, 2023.

However, panel b, based on production data, provides cause for concern.

Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States do not mine

(produce) graphite in significant quantities (the European Union also has only

limited graphite mining). In contrast, China produced nearly two-thirds of all

graphite mined globally in 2022. Countries other than China are thus likely

sourcing their raw graphite from foreign sources—likely China. Thus, what

appears to be a diverse set of foreign sources for EU graphite imports (panel a)

14 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

is merely a statistical artifact of the 6-digit Harmonized System code capturing

products beyond those found in the Chinese export restrictions. The implication

is that, if China applied its export restriction on raw graphite universally, then

Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and the United States would be cut

off as well, and the European Union would no longer be able to import graphite

products from them or China.

The European Union’s dependence on China for graphite both illustrates

the problem policymakers seek to address and shows why examining

trade dependencies alone is not enough, as Mejeun and Rousseaux note.

35

Furthermore, graphite is different from other minerals needed for EV batteries

like lithium and cobalt, for which China’s supply chain choke point is not the

mining but the mineral-processing stage.

36

The difference reveals the complexity

of understanding how a country might weaponize a supply chain.

For most other products, the informational challenge facing policymakers

is often worse. Critical minerals are among the few goods for which global

production data are available. Product-level production data are not available for

most manufactured goods of concern for economic security.

3.2 Is China trading more with the European Union because of the US–

China trade war?

Before turning to EU policy instruments, consider a separate question motivated

by the Chinese EV example. Are other economic forces pushing the European

Union to trade more with China—including by importing products like EVs—and

are these forces working against the European desire to de-risk unilaterally?

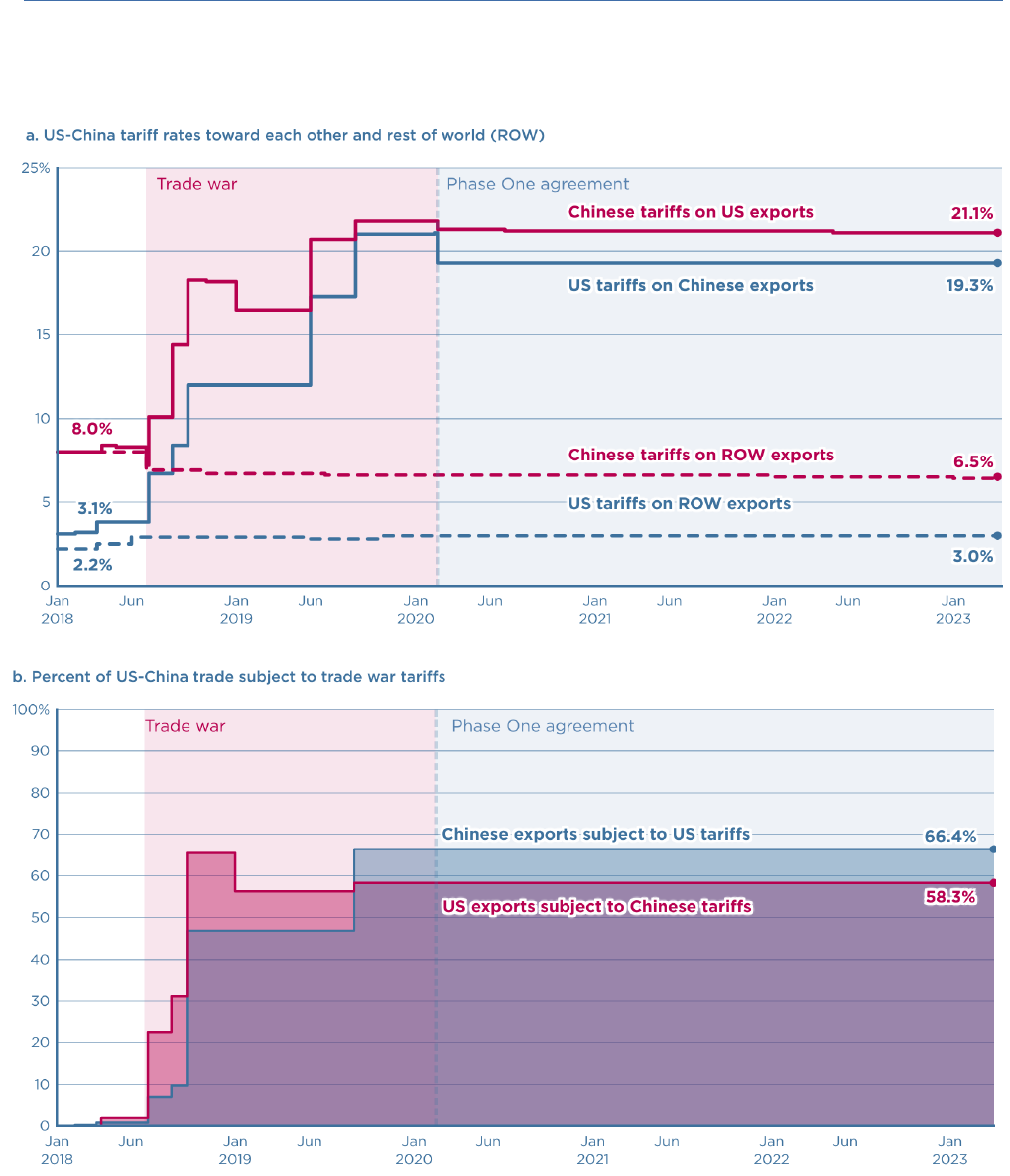

One such force may arise from the remnants of the (ongoing) US–China trade

war. In July 2018, the United States began to impose additional tariffs on a range

of imported goods from China. China retaliated in kind. By the time the two

countries paused their tariff escalation, in early 2020, new US and Chinese tariffs

covered more than half of their bilateral trade (figure 5). The average US tariff

on imports from China, for example, increased from 3 percent to 19 percent.

37

In part because the European Union and the United States are similar, high-

income consuming economies, if the US tariffs stopped potential Chinese exports

from entering the United States, then Chinese exports may be surging into the

European Union and other third-country markets (trade deflection).

38

Increasing

the chances of this happening is the fact that China also reduced its tariffs

toward the European Union and other third countries throughout the trade war.

39

35 Put differently, graphite would presumably be identified as a strategically dependent product

under a separate criterion examined by Mejean and Rousseaux (forthcoming) that takes into

consideration EU production capacities (which, in the case of graphite, are minimal).

36 Much of the mining of these and other critical minerals outside China is also done by Chinese

firms or joint ventures with Chinese firms, which raises separate issues (Leruth et al. 2022).

37 For an analysis of the US–China trade war, see Bown (2021).

38 For early evidence of trade deflection, see Bown and Crowley (2007). For early evidence from

the US–China trade war, see Fajgelbaum et al. (forthcoming).

39 See Chad P. Bown, Euijin Jung, and Eva Zhang, “Trump Has Gotten China to Lower Its Tariffs.

Just Toward Everyone Else,” PIIE Trade and Investment Policy Watch, June 12, 2019.

15 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Figure 5

US and Chinese import tariffs toward each other increased considerably

during the trade war of 2018-19 and have remained elevated since

Source: Bown (2023b).

16 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

As part of the initial wave of tariffs, in July 2018, the United States imposed

25 percent duties on automobiles from China, including EVs, even though China

was not yet exporting EVs in great numbers to anyone (see figure 1). China’s

immediate tariff retaliation included hitting US EV exports and likely accelerated

what was already going to turn into a profound shift in EV trade patterns. China’s

tariffs first contributed to the United States suddenly losing its considerable EV

exports to China, as Tesla accelerated construction of its gigafactory in Shanghai.

The United States then lost its EV exports to the European Union, as Tesla

switched to exporting to the European Union from its new Chinese plant.

40

As of late 2023, China was not exporting many EVs to the United States, in

part because of the additional US trade war tariffs of 25 percent. (US lawmakers

have called for increasing US tariffs on Chinese EVs still further.

41

) In contrast,

China’s exports to the European Union had soared to over $14 billion—more than

3 times the 2021 level and roughly 17 times the levels in 2020 (see again figure 1).

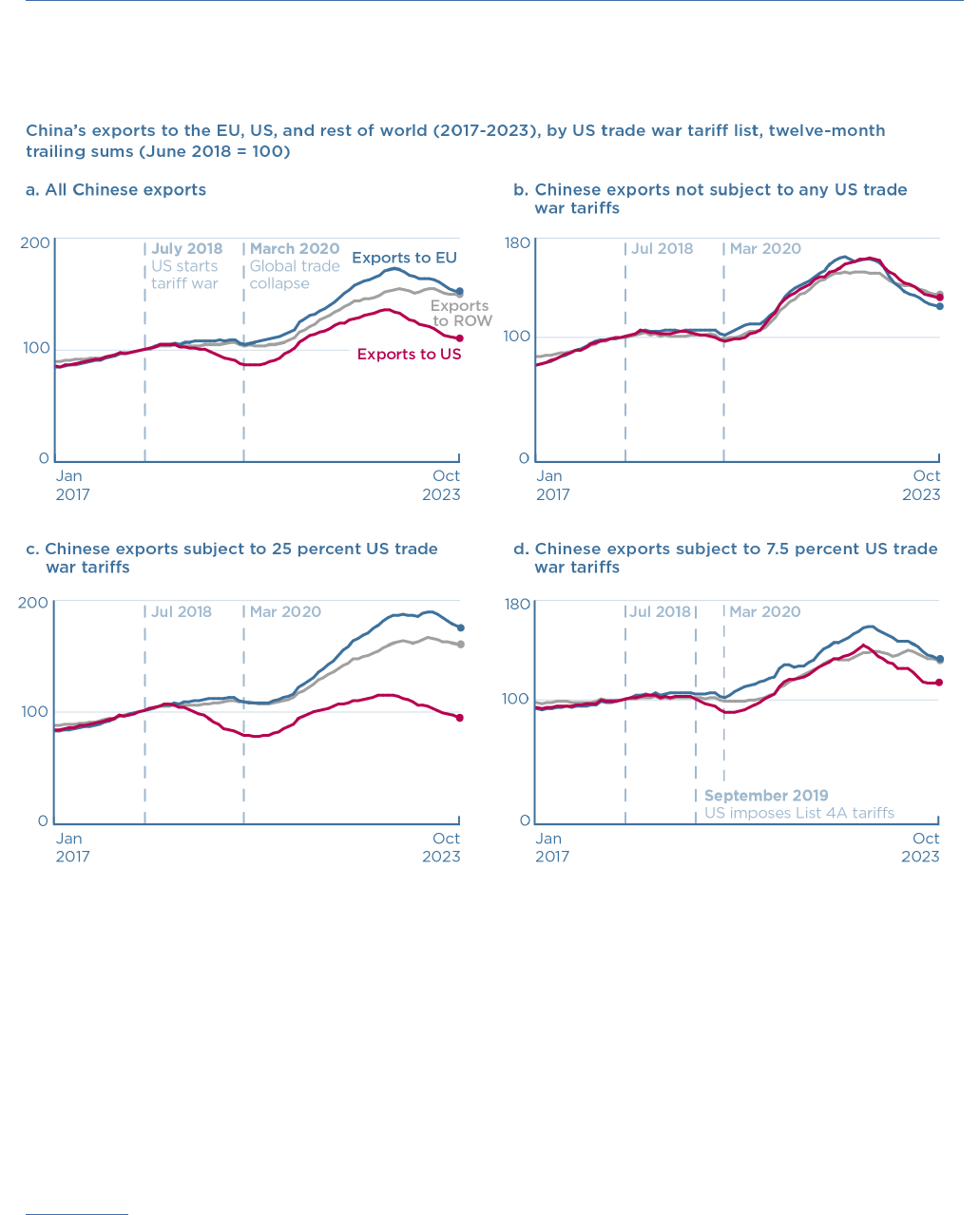

More generally, there is some evidence beyond EVs that China is exporting

more to the European Union because it cannot export to the United States (figure

6). As a starting point, consider China’s exports in June 2018, the month before the

trade war started. By October 2023, China’s total exports to the European Union

had grown by 52 percent, whereas its total exports to the United States had grown

by only 10 percent.

42

These results mask considerable heterogeneity, given that

not all Chinese products were hit with US tariffs. For products not hit with any US

tariffs, Chinese export growth to the United States since June 2018 was higher than

export growth to the European Union (panelb of figure 6).

These results contrast with those for Chinese exports of products subject

to the 25 percent US tariffs. Chinese exports to the European Union of those

products rose 77 percent between June 2018 and October 2023, whereas exports

to the United States declined 5 percent (figure 6, panel c).

43

These tariffs affected

$271 billion of annual Chinese exports to the European Union in the 12 months

ending in October 2023.

The intermediate case involves products subject to US tariffs of only

7.5percent (figure 6, panel d). For these products, the difference between the

growth of Chinese exports to the European Union and its exports to the United

States was only 21 percentage points.

A similar trade-diverting phenomenon has likely arisen in the context of EU

exports to China.

44

As part of the trade war, China retaliated with its own tariffs,

40 See Figures 3 and 4 of Bown (2023a), and the discussion therein.

41 David Shepardson, “US Lawmakers Want Biden to Hike Tariffs On Chinese-Made Vehicles,”

Reuters, November 8, 2023.

42 A separate issue involves the extent to which even the US tariffs are affecting supply chains

beyond the movement of final assembly before shipment to the United States (Chad P. Bown,

“Four Years Into the Trade War, Are the US and China Decoupling?” PIIE Realtime Economics,

October 20, 2022). Freund et al. (2023) suggest perhaps not and provide evidence that foreign

sources replacing China are deeply integrated into China’s supply chains and themselves have

experienced faster import growth from China.

43 These results are not driven exclusively by EVs. Dropping EVs from panel c implies that by

October 2023, there was still a 73 percentage point difference between the growth of Chinese

exports to the EU versus the US for products hit with 25 percent US tariffs since June 2018.

44 Assessing Chinese imports in a way like that shown in figure 6 is complicated by uncertainty

over which products have continued to apply binding tariffs on US exports; it is difficult to

assess, given the purchase commitments in the Phase One agreement of January 2020 (Bown

2021).

17 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Figure 6

Is China deflecting exports to the European Union of products hit by US

trade war tariffs?

ROW = rest of world; US = United States; EU = European Union

Source: Constructed by the author with data from UN ITC Trade Map.

which hurt US exports to China. Despite the US–China Phase One agreement of

January 2020—in which China promised to purchase an additional $200 billion of

US goods and services exports over 2020–21—US exports to China have mostly

not resumed.

45

For manufactured goods especially—the most comparable part

of US and EU exports to China—US exports to China remain below pre-trade war

levels (figure 7, panel a). Unsurprisingly, China increased its imports from the

European Union, a pattern that was not reversed when the Phase One agreement

went into effect.

45 See Chad P. Bown, “China Bought None of the Extra $200 Billion of US Exports in Trump’s

Trade Deal,” PIIE Realtime Economics, February 8, 2022; Chad P. Bown and Yilin Wang, “Five

Years into the Trade War, China Continues Its Slow Decoupling from US Exports,” PIIE Realtime

Economics, March 16, 2023.

18 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Figure 7

China is buying more EU exports and less US exports of manufactured goods

since the trade war

ROW = rest of world; US = United States; EU = European Union

Notes: EU exports converted to US dollars from euros using end of month USD/euro spot exchange rate

from Federal Reserve Economic Data (DEXUSEU).

Source: Constructed by the author with data from US Census (via Dataweb), Eurostat, and UN ITC Trade

Map.

19 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

China cut automobile sector imports from the United States during the trade

war. In contrast, its imports from the European Union remained high, though

they have slowed recently (panel b of figure 7). These factors highlight some of

the German policymaker concerns over German automakers being excessively

dependent on the Chinese market.

46

Overall, these data raise important questions about any EU de-risking

strategy. Economic forces external to the EU–China relationship are pushing the

European Union to trade relatively more with China, not less. If the European

Union seeks to de-risk and European firms do not face all of the societal

incentives to do so, the European Union may need to undertake explicit policy

actions to adjust their incentives.

4. POLICIES TO REDUCE ECONOMIC INSECURITY

The European Union and other governments can deploy multiple policy

instruments to alter firm incentives. This section focuses on five of them:

inventory management, supply-side subsidies, tariffs, export controls, and foreign

investment regulations. It explores examples of how governments are using these

policies for reasons that are consistent with an effort to improve their economic

security. Although the emphasis remains on EU interests, some of the novel

policies worth discussing arise from other countries. This section also reviews

existing WTO system rules (where applicable) as well as potential tweaks to

those rules that might be incorporated to facilitate the use of those instruments

to help achieve domestic policymakers’ objectives.

The working assumption is that policymakers want to balance multiple

objectives. One is to maintain access to critical goods across more states of the

world—even when there is the realization of bad shocks—but recognizing that

bad shocks can also occur at home. However, there is also acknowledgment that

the current geographic concentration of production of certain goods increases

the probability of certain bad shocks; given policymaker uncertainty that firms

are internalizing those risks, government officials may want to create additional

incentives to shift the location of production (or shift it more quickly). Finally,

there is recognition that in the worst states of the world (war, pandemic), a local

supply chain is preferable, because policymakers can compel it to do things they

cannot if production is conducted abroad.

4.1 Inventory management

Holding inventories is one way to help smooth consumption across good and bad

states of the world. Stockpiling can make it more difficult for a malicious foreign

policymaker to impose effective export restrictions. Establishing a credible threat

to release previously produced supplies onto the market to dampen any adverse

price effects could dissuade malevolent policy.

Perhaps the most famous example of stockpiling as such a tool of economic

policy is the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR), an emergency stockpile of

petroleum that the US government established in 1975 after suffering through

46 Germany and the Slovak Republic accounted for 90 percent of EU exports of autos to China in

2023; one of the Slovak Republic’s largest auto production complexes belongs to Volkswagen.

20 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

the economic shocks of shortages and inflation induced by the 1973 OPEC–led oil

embargo. In 2022, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the United States sold

off over 40 percent of the SPR to help limit rising fuel prices globally.

47

In the

European Union, there have been discussions about whether to create a strategic

natural gas reserve. One debate is whether such an arrangement may have eased

the pain or even deterred Russia’s withholding of natural gas exports in 2022 or

in the 2021 lead-up to its February 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

48

Other stockpiling examples are not necessarily motivated by concerns

over cartel-like behavior. In the United States, the Strategic National Stockpile

(SNS) is tasked with maintaining an adequate US inventory of PPE in case of

a public health emergency. The SNS was quickly exhausted early on in the

COVID-19 pandemic, however, leading to PPE shortages with tragic public

health effects (Bown 2022a; Joskow 2022), illustrating how the existence of a

stockpiling program does not imply that it will work in the face of an adverse

shock. (Although it was not weaponized, PPE also did turn out to have had

geographically concentrated production in China.)

Some countries, including India, hold stockpiles of food.

49

With respect to

WTO rules, these stockpiles have become very contentious, as they can conflict

with explicit national commitments to limit subsidies for food products under the

WTO’s Agreement on Agriculture.

50

In the 1970s, stockpiling took on a prominent role in public policy debates out

of fear over cartels for oil and other commodities (Nichols and Zeckhauser 1977).

But inventory management for economic security has its own policy challenges

and tradeoffs. Holding inventories is costly. Governments in power may also

be unable to resist releasing stockpiles for political reasons—to lower prices

to benefit consumers right before an election, for example—making inventory

management for economic security reasons difficult to sustain.

Nevertheless, given that the private sector can hold inventories, it is also

important to understand the nature of any market failures that would create a

role for government. One potential explanation is scale: The size of the optimal

stockpile may be sufficiently large that no private sector actors may emerge. A

second is the potential time-inconsistency problem. Although policymakers may

encourage stockpiling, the private sector may fear that the emergence of a crisis

that causes them to draw down (and profit from) their inventories will make

policymakers reverse course by imposing price controls or taxing “excess profits,”

thereby eliminating the value of the private sector’s investments. (The inability of

policymakers to tie their own hands discourages the private sector from creating

stockpiles in the first place.)

47 Ben Lefebvre, “Biden Sold Off Nearly Half the US Oil Reserve. Is It Ready for a Crisis?” Politico,

October 16, 2023.

48 S&P Global, “Time for Europe and the IEA to Create a Strategic Gas Reserve,” Commodity

Insights, September 27, 2021. Beginning in mid-2021, months before invading Ukraine, Russia

limited natural gas exports to Europe to long-term contracts and ended spot market sales (US

Energy information Administration, “Russia’s Natural Gas Pipeline Exports to Europe Decline to

Almost 40-Year Lows,” August 9, 2022).

49 See Pratik Parija, Anup Roy, and Bibhudatta Pradhan, “India’s Grain Stockpiles Key to Modi’s

Pre-Election Strategy,” Bloomberg, August 8, 2023.

50 For a discussion, see Glauber and Sinha (2021).

21 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Finally, inventories are feasible only for certain types of goods. Stockpiling

cannot work for goods that need to be invented to address an emergency, such

as new diagnostics, treatments, or vaccines in response to a pandemic. Holding

inventories will also be less effective at addressing shortages of goods with quick

product cycles—such as advanced node semiconductors—whose value starts

high but then may diminish quickly as they are replaced by newer products.

4.2 Production subsidies and the management of capacity utilization

One way to incentivize the movement of a supply chain away from its current

location is through a subsidy. In theory, there are at least two ways to condition

the subsidy. One is to grant it provided the supplier leaves its current location.

Another is to allocate it if the firm arrives (and starts investing or producing) in a

particular location. This distinction has become important, as explored below.

51

One potential benefit to a subsidy may be increased diversification and thus

continued provision of output in certain states of the world, such as when a

foreign shock might otherwise have cut off supplies. There may also be spillovers

if the subsidy moves production to a local supplier, giving local policymakers

greater control (or responsiveness) in case of an emergency. In the case of

COVID-19 vaccine production, for example, US government use of the Defense

Production Act and priority-rated contracting was likely effective at triggering an

earlier and larger production response than it would have had the United States

not had local manufacturing capacity.

52

Subsidies are also costly, however, for several reasons. First, subsidies

involve fiscal costs. Second, efficiency costs may emerge if forced diversification

results in firms producing at a smaller scale or otherwise losing access to local

agglomeration externalities. Ongoing subsidization may be required if the

objective is to maintain domestic production in the new environment even if the

new industry is not competitive with foreign firms. (An alternative would be less

efficient protection via tariffs.)

Even subsidies to maintain some domestic production do not guarantee

greater responsiveness to an emergency, however. For example, the US

government funded a program to keep production capacity for vaccines

set aside (in reserve) in case of a pandemic. But the contractor, Emergent

BioSolutions, mismanaged the manufacturing process of the Johnson & Johnson

and AstraZeneca vaccines when COVID-19 hit, forcing it to destroy hundreds of

millions of doses of the vaccines (Bown and Bollyky 2022). (This transgression

has been largely forgiven by history, because of the success of mRNA vaccines

by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna, which made those tainted vaccines superfluous

for the US market.)

Existing WTO rules have two main concerns with subsidies.

53

The first is that

the WTO prohibits subsidies contingent on local content (as opposed to the use

of imported inputs) or exports. The second involves the potential international

51 For a new database on contemporary use of industrial policy, see Evenett et al. (2024).

52 For a discussion of DPA and priority-rated contracting as it was applied to COVID-19 vaccine

supply chains, see Bown (2022a). For recent EU proposals, see Aurélie Pugnet, “European

Commission Mulls New European Defence Act before End of Year,” Euractiv, September 4,

2023.

53 For a discussion, see Bown (forthcoming).

22 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

economic externalities of the subsidy and whether it erodes the partner’s

expected access to the EU or third-country markets. Such harmful effects—which

are likely to emerge for large producing economies like the European Union—

make these subsidies “actionable” and subject to a policy response by the

adversely affected trading partner. The cost–benefit calculation influencing the

European Union’s decision on whether to impose a subsidy may thus also need to

consider additional costs, such as the lost export market access for a different EU

industry if its subsidy induces (WTO–consistent) retaliation by the trading partner.

The next sections highlight examples of governments using subsidy policies

in an attempt to de-risk. It also describes some government efforts to subsidize a

supply chain to leave one country and go into a third country.

4.2.1 The Inflation Reduction Act and US subsidies for critical minerals

Under the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of 2022, the United States has developed

a creative approach for subsidizing the creation of supply chains outside of

China. In trade circles, the IRA is best known for the local content requirement

of its EV consumer tax credits under Section 30D, which led to trade disputes

with Europe and South Korea that the Biden administration resolved through a

regulatory decision in which subsidies for leased EVs were exempt from the local

content requirement (Bown 2023a, 2024).

For critical minerals and materials, however, more important are Section

30D’s provisions requiring that, over time, even vehicles assembled in North

America cannot receive the consumer tax credit if these key battery inputs

continue to be sourced from China. The law also implicitly recognizes that many

critical minerals are unlikely to be mined or processed in the United States.

It therefore allows for tax credit eligibility if the critical minerals are sourced

from a US free trade agreement (FTA) partner. In a March 2023 decision, the

US Treasury expanded the definition of free trade agreement partner to extend

beyond the 20 countries with which the United States has a Congressionally

approved FTA to include other countries with which the US government might

negotiate critical minerals agreements.

To date, the United States has negotiated such a critical minerals agreement

with only one country (Japan) to completion; it is in talks with the European

Union and the United Kingdom. There have also been public reports of requests

from other countries, such as Indonesia and the Philippines. South Korean battery

companies (which have significant manufacturing plants in the United States)

have lobbied the United States to negotiate such agreements with Indonesia

and Argentina, presumably because they source critical minerals from those

countries.

54

The United States has been unresponsive to date, in part because

much of the nickel industry in Indonesia involves Chinese ownership or joint

ventures of local firms with Chinese firms.

55

These arrangements may therefore

not address the concerns over supply chain control driving US worries over its

economic security.

54 Kyongae Choi, “Finance Minister Calls for US Cooperation in IRA Guidance on Critical Minerals,”

Yonhap News Agency, February 26, 2023.

55 Mercedes Ruehl, Christian Davies, and Harry Dempsey, “Indonesia Business Presses US over

Green Subsidies for EV Minerals,” Financial Times, March 29, 2023.

23 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

As neither the European Union nor the United States is likely to mine or

process significant amounts of critical minerals domestically, a bilateral critical

minerals agreement may not be particularly valuable to either. Nevertheless,

European automakers and battery manufacturers would likely benefit from

creation of a separate critical minerals supply chain outside of China that could

result from US policy incentives. Even if European automakers continue to source

from China, the existence of alternative suppliers would reduce China’s supply-

side market power, to the benefit of all potential buyers.

Of course, creating additional supply chains to limit China’s ability to

weaponize its exports is a costly approach to tackling the climate crisis. It would

be more efficient globally to negotiate new rules with China to discipline its use

of export restrictions as part of a bigger package of cooperation on trade and

climate (Bown and Clausing forthcoming).

4.2.2 Japan’s “China exit” subsidies

Japan’s recent efforts illustrate a second example of creative subsidies to de-

risk from China. In the face of early COVID-19 supply chain disruptions facing

Japanese firms in China, the Japanese government earmarked $2.2 billion in

April 2020 to “China exit” subsidies—subsidies for the affiliates of Japanese-

headquartered firms to leave China. Nearly 10 percent of the funding—and 30

of the 87 projects announced in July 2020—involved the Japanese government

subsidizing firms to move production from China to third countries in Southeast

Asia, such as Laos, Vietnam, and Malaysia,

56

in part to take advantage of

comparative advantage and the existence of local, pre-existing supply chains.

Although some production lines involved PPE and other COVID-19-related

products—and thus were in response to immediate concerns of supply shortages

coming out of China—subsidies were also granted to Japanese firms making

products completely unrelated to the pandemic, including aviation parts, auto

parts, and fertilizer.

4.2.3 Subsidies and coordination of the movement of semiconductor supply

chains

There are multiple issues of concern about the future location of production

of semiconductors. One is the subsidies China has provided to the industry

(OECD 2019) and its stated goal (in the Made in China 2025 industrial policy) to

dominate the sector globally, which could result in it having supply-side market

power that it could weaponize. Another potential concern involves the existing

geographic concentration of semiconductor production in East Asian hotspots

(Taiwan, South Korea), especially the most advanced nodes in Taiwan, by TSMC.

The semiconductor shortages that arose in 2021 hurt Europe. German

automakers in particular were forced to cut back production, with considerable

impact on the German economy.

57

56 See Isabel Reynolds and Emi Urabe, “Japan to Fund Firms to Shift Production out of China,”

Bloomberg, April 8, 2020; Nikkei Asia, “Japan Reveals 87 Projects Eligible for ‘China Exit’

Subsidies,” July 17, 2020.

57 Joe Miller and Martin Arnold, “Car Chip Shortage Weighs on German Economy,” Financial

Times, July 7, 2021.

24 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

Two main factors drove the auto industry shortage. The first was global

automakers’ decision to pull semiconductor orders in response to the mobility

restrictions imposed in early 2020 because of the pandemic. The second was

that, seeing heightened demand because of those restrictions, semiconductor

manufacturers quickly replaced those orders with higher-value chips from

consumer electronics firms.

58

As a result, when mobility restrictions were

lifted and automakers tried to place new orders later in the year, there was a

major backlog, as semiconductor manufacturers were operating at capacity

and producing more profitable varieties of chips. The experience heightened

European policymaker awareness that Europe had a dwindling share of global

chip manufacturing and thus little control over the supply chain in the event of

an emergency.

59

Since then, policymakers have sought both to diversify more

production out of East Asia and to bring some of it to Europe, in part to retain

some control over suppliers in the event of future shocks.

Germany has reportedly offered as much as €5 billion of subsidies for TSMC

to construct a manufacturing facility in Dresden. The complex arrangement

involves equity stakes by NXP, Infineon, and Bosch and thus required sign-off

over any anti-trust concerns by the German cartel office.

60

Other countries are also working to diversify TSMC’s production outside

of Taiwan. Japan granted over $3 billion in subsidies to the company to build

a facility on the island of Kyushu.

61

The United States is expected to subsidize

TSMC’s construction of a plant in Arizona once it begins to disburse funding

made eligible under the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022.

62

Germany has also promised Intel nearly €10 billion of subsidies for two plants

in Magdeburg.

63

Intel has also received subsidies for a new assembly, packaging,

and test facility in Poland, which is likely to service the German plants.

64

France

will provide €2.9 billion of subsidies to GlobalFoundries for a new facility with

STMicroelectronics in southeastern France.

65

58 See Semiconductor Industry Association, “Semiconductor Shortage Highlights Need to

Strengthen U. Chip Manufacturing, Research,” Blog, February 4, 2021.

59 In May 2021, the US government reportedly contemplated using the Defense Production Act

to forcibly allocate some production of chips toward similarly harmed auto plants in the United

States. It decided against it, because doing so would have simply reallocated semiconductors

away from goods like consumer electronics that were still in high demand because of

pandemic-era mobility restrictions requiring work from home and school from home. (See

Trevor Hunnicutt, Andrea Shalal, and David Shepardson, “Exclusive: Facing Chips Shortage,

Biden May Shelve Blunt Tool Used in COVID Fight, Reuters, May 5, 2021.)

60 See Debby Wu and Aggi Cantrill, “TSMC to Build $11 Billion German Plant with Other

Chipmakers,” Bloomberg, August 8, 2023; Linda Pasquini, “Germany Approves Stakes by

Bosch, Infineon and NXP in TSMC Chip Plant,” Reuters, November 7, 2023.

61 Kana Inagaki, “How TSMC’s Chip Plant Is Shaking Up Japan,” Financial Times, September 25,

2023.

62 Cecilia Kang, “How Arizona Is Positioning Itself for $52 Billion to the Chips Industry,” New York

Times, February 22, 2023.

63 Friederike Heine, Supantha Mukherjee, and Andreas Rinke, “Intel Spends $33 Billion In Germany

In Landmark Expansion,” Reuters, June 19, 2023.

64 Karol Badohal and Supantha Mukherjee, “Focus: How Poland Snagged Intel’s Multi-Billion

Dollar Investment,” Reuters, June 22, 2023; Intel, “Intel Plans Assembly and Test Facility in

Poland,” Press release, June 16, 2023.

65 Dominique Vidalon and Sudip Kar-Gupta, “France to Provide 2.9 Billion Euros in Aid for New

STMicro/ Globalfoundries Factory,” Reuters, June 5, 2023.

25 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

It is noteworthy that Europe and other key US allies have provided government

support to US–headquartered companies like Intel, GlobalFoundries, Micron, and

IBM, given that most of these companies are expected to apply for and receive

CHIPS Act funding that also expands US–based production. (Micron will also

receive $1.3 billion from the Japanese government for a factory in Hiroshima,

66

and IBM has partnered with Rapidus, a newly formed Japanese semiconductor

manufacturer, to produce advanced-node chips in Japan.

67

) Although the CHIPS

Act included guardrails to prevent companies that accept US funding from

expanding their manufacturing facilities in China, the US administration has not

complained about allied countries subsidizing US–headquartered firms.

Under the CHIPS Act, the United States also has created incentives similar

to Japan’s China exit/third-country subsidies. Up to $500 million may be used

to subsidize assembly, packaging and test facilities in labor-abundant countries

outside the United States. In 2023, for example, the United States announced

that it was exploring such partnerships with Panama, Costa Rica, and Vietnam.

68

(Intel, for example, already has facilities in Costa Rica and Vietnam.)

Many, including prominent European policymakers,

69

have described the

proliferation of state funding for semiconductors as simply a “subsidy war.” While

this is a risk, a more nuanced view is that Europe and the United States have

common objectives and would benefit from coordinating their uses of industrial

policy. Even before the inauguration of the Biden administration, in January 2021,

the European Commission released a blueprint seeking to reboot transatlantic

ties after the Trump administration.

70

The Biden administration has made similar

efforts; the United States and the European Union established the Trade and

Technology Council early in 2021, using it, in part, to discuss coordination of their

industrial policies for semiconductors. This information-sharing has also extended

to Japan, a country with common concerns.

71

Nevertheless, not all subsidies that these governments are disbursing are in

this vein. In Japan, for example, 90 percent of the 2020 China exit subsidies were

66 Yoshiaki Nohara, “In Boost for Chip Ambitions, Japan Inks $1.3 Billion in Subsidies for Micron

Plant,” Bloomberg, October 2, 2023.

67 Tim Kelly and Jane Lee, “IBM Partners with Japan’s Rapidus in Bid to Manufacture Advanced

Chips,” Reuters, December 12, 2022.

68 See US State Department, “Department of State Announces Plans to Implement the CHIPS

Act International Technology Security and Innovation Fund,” Press release, March 14, 2023;

US Department of State, “New Partnership with Costa Rica to Explore Semiconductor Supply

Chain Opportunities,” Press Release, July 14, 2023; US Department of State, “New Partnership

with Panama to Explore Semiconductor Supply Chain Opportunities,” Press Release, July 20,

2023; US Department of State, “New Partnership with Vietnam to Explore Semiconductor

Supply Chain Opportunities,” Press release, September 11, 2023; Francesco Guarascio, “Vietnam

Eyes First Semiconductor Plant, US Officials Warn of High Costs,” Reuters, October 30, 2023;

Reuters, “Intel to Invest $1.2 Bln In Costa Rica over Next Two Years,” August 30.

69 “‘It’s like a declaration of war,’ Robert Habeck, Germany’s vice-chancellor and economics

minister, said last month. . . . ‘The [Americans] want to have the semiconductors, they want

the solar industry, they want the hydrogen industry, they want the electrolysers,’ Harbeck told

a business conference.” See Guy Chazan, Sam Fleming, and Kana Inagaki, “A Global Subsidy

War? Keeping Up with the Americans,” Financial Times, July 13, 2023.

70 European Commission, “A New EU–US Agenda for Global Change,” Joint Communication to

the European Parliament, European Council and the Council, December 2, 2020.

71 See Yuka Hayashi, “US, EU Agree to Coordinate Semiconductor Subsidy Programs,” Wall

Street Journal, December 5, 2022. Rihao Nagao, “Japan and EU to Share Chip Subsidy Info to

Disperse Production. Three-Way Exchange with US Aims for Better Supply Chain Distribution,”

Nikkei Asia, June 29, 2023.

26 WP 24-2 | JANUARY 2024

earmarked for production to leave China by returning to Japan. For PPE, the US

government spent over $1 billion in 2020–21 to subsidize the creation of entire

domestic supply chains in response to the shortages arising during the early days

of COVID-19 (Bown 2022a). In the IRA, a plethora of local content provisions

attempts to incentivize clean energy projects to disproportionately rely on US–

made inputs like steel.

4.3 Tariffs

Tariffs are another instrument potentially affecting supply chains. They can be

used to address two different margins.

First, a government can raise its tariffs on all trading partners—by, for

example, raising its most favored nation (MFN) tariff. Doing so creates incentives