IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

Author: Jana Titievskaia

Members' Research Service

PE 642.229 – October 2019

EN

EU trade policy

Frequently asked

questions

This paper seeks to serve as a key resource for policy-makers who need to understand complex issues related

to international trade quickly. It also outlines the key academic debates and thorny issues and provides

references to potentially useful further resources. The paper does not cover the state of play of trade

negotiations or legislative files as these are covered in other EPRS publications.

The Legislative Train Schedule for trade monitors progress on key legislative files and trade agreements on a

monthly basis.

EPRS publications on international trade include short 'at a glance' notes on topical trade issues and

'international agreements in progress' briefings, as well as longer, more in-depth papers.

AUTHOR(S)

Author: Jana Titievskaia, Members' Research Service. Graphics by the author.

This paper has been drawn up by the Members' Research Service, within the Directorate-General for

Parliamentary Research Services (EPRS) of the Secretariat of the European Parliament.

To contact the authors, please email: [email protected]pa.eu

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

Translations: DE, FR

Manuscript completed in September 2019.

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

This document is prepared for, and addressed to, the Members and staff of the European Parliament as

background material to assist them in their parliamentary work. The content of the document is the sole

responsibility of its author(s) and any opinions expressed herein should not be taken to represent an official

position of the Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

Brussels © European Union, 2019.

Photo credits: © 9dreamstudio / Fotolia.

PE 642.229

ISBN: 978-92-846-5673-8

DOI:10.2861/583720

CAT: QA-01-19-761-EN-N

[email protected]ropa.eu

http://www.eprs.ep.parl.union.eu (intranet)

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank (internet)

http://epthinktank.eu (blog)

EU trade policy

I

Executive summary

The EU's common commercial policy (CCP), or trade policy, has evolved gradually over the years to

encompass a range of trade-related areas under the remit of European Union (EU) exclusive

competence. The Treaty of Rome established the common market and the customs union with a

focus on goods. Later treaties expanded the CCP to services and commercial aspects of intellectual

property rights. Trade policy falls under the EU's exclusive competence, meaning that the EU

manages trade policy and trade negotiations on behalf of the Member States. The determination of

competence is critical for the procedures needed to conclude trade agreements, as in areas falling

under shared competence these need to be ratified by both the EU and Member States. This has

led to trade and investment agreements being split into two parts to speed up the ratification

process for the trade parts, following European Court of Justice (ECJ) Opinion 2/15 (Singapore).

Whereas trade liberalisation is generally accepted to lead to economic growth, the impact on jobs

varies both between and within countries. According to the European Commission, in 2018 trade

supported 36 million export-related jobs. Trade can also lead to more inequality, however, in

particular by widening the gap between skilled and unskilled workers or in causing the unequal

relationship between developed and developing countries to become more entrenched.

Trade liberalisation in its most basic form involves the removal of tariffs, which are taxes or duties

to be paid for an import. Tariff rate quotas charge lower rates within a certain quota, jumping to a

higher tariff rate after the quota is exhausted. Tariffs are cut under World Trade Organization (WTO)

agreements, with the most-favoured nation tariff representing the highest possible tariffs that WTO

members can charge each other. In contrast, preferential tariffs are agreed to in trade agreements

or customs union arrangements. Rules of origin have been developed in order to determine where

goods originate from (or the 'economic nationality' of products). These rules are all the more

important in the era of global value chains, where a significant proportion of European products'

value comes from foreign sub-components or services.

Trade liberalisation also seeks to remove non-tariff barriers (NTB) to trade, these include

protectionist measures to help domestic producers, subsidies, technical barriers to trade, or

stringent sanitary and phytosanitary requirements. Lower NTBs can facilitate cross-border trade in

services, which play a huge role in overall EU trade. However, data collection and measurement

issues complicate efforts to understand the services trade. Trade defence instruments, meanwhile,

enable the EU to react, for instance, to dumping or WTO-incompatible subsidies in partner trading

countries, and form the protective front of EU trade policy.

The CCP focuses on fostering fair and free trade, furthering market access and supporting the

multilateral, rules-based trading system. To achieve these objectives, the EU employs a range of

legislative tools and negotiates trade agreements with trade partners. More specifically, over recent

decades the EU has aimed to spread open and free trade based on mandates from Member States.

After the breakdown of the WTO Doha Round, the EU initiated a period of concentrated focus on

free trade agreements, which tackle both tariff liberalisation and NTBs, with a wide range of partner

countries from America to Asia.

The EU has concluded trade agreements on multilateral, plurilateral and bilateral bases. EU trade

agreements are adopted through a lengthy procedure, which involves distinct stages, namely

preparation, a mandate to open talks, negotiations, textual agreement, initialling, signature,

provisional application and, finally, entry into force. The EU also offers different types of trade

relationship, ranging from deep integration on both regulatory and trade fronts, to simple

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

II

partnership and cooperation agreements that do not offer preferential treatment. Trade

agreements are enforceable through a dedicated dispute settlement mechanism that allows

parties to adopt economic remedies in the event of non-compliance. However, certain provisions in

trade agreements, such as trade and sustainable development (TSD) clauses, have a different

mechanism for settling disagreements that involves government consultations and

recommendations issued by a panel of experts. Efforts to make trade policy 'greener' include TSD

chapters, but also provisions to support sustainable use of natural resources, biodiversity, forestry

and fisheries. Trade agreements also include human rights clauses that aim to incentivise trade

partners to improve internal governance.

EU trade legislation is adopted under the ordinary legislative procedure, and provides the

framework for trade policy. Since the Lisbon Treaty, the European Parliament has played an

important role in the CCP. Parliament must give its consent to trade agreements or trade-related

legislation, while it also monitors trade policy developments through resolutions, hearings and

workshops. The European Commission proposes and negotiates, while the Council authorises the

opening of negotiations and decides on the conclusion of trade agreements. Civil society and

stakeholders are encouraged to feed into this process on a regular basis.

Where technocratic negotiations were once sufficient, trade policy has undergone intense

politicisation in recent years. Where trade policy used to be characterised by material arguments

based on numerical simplicity, now it features normative disagreements and regulatory politics. This

makes knowledge and understanding of the complex concepts and themes of EU trade policy all

the more important.

EU trade policy

III

Table of contents

1. Introduction _________________________________________________________________ 5

2. Background: evolution and scope of the common commercial policy ___________________ 5

2.1. The common commercial policy: from coal and steel to services and foreign direct investment

____________________________________________________________________________ 5

2.2. Evolution and scope of trade competences ______________________________________ 8

3. Economics of trade ____________________________________________________________ 9

3.1. Does trade lead to economic growth in the EU? __________________________________ 9

3.2. Does trade create or cut jobs in the EU? ________________________________________ 10

3.3. Does trade lead to inequality in the EU? ________________________________________ 11

4. Key trade concepts ___________________________________________________________ 12

4.1. How do tariffs work? _______________________________________________________ 12

4.2. What are rules of origin? ____________________________________________________ 13

4.3. What are non-tariff barriers to trade? __________________________________________ 13

4.4. How are services traded? ____________________________________________________ 14

5. Formulation of EU trade policy _________________________________________________ 15

5.1. What are the aims of EU trade policy? _________________________________________ 15

5.2. What are the roles of EU institutions in trade policy? _____________________________ 16

5.2.1. What does the European Parliament do? ____________________________________ 16

5.2.2. What does the European Commission do? ___________________________________ 16

5.2.3. What does the Council do? _______________________________________________ 16

5.3. How is civil society involved in EU trade policy? _________________________________ 17

6. EU trade-related legislation ____________________________________________________ 18

6.1. What are the different EU laws relating to trade? ________________________________ 18

6.2. What are trade defence instruments? __________________________________________ 19

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

IV

6.2.1. What are anti-dumping duties? ____________________________________________ 19

6.2.2. What are anti-subsidy measures? __________________________________________ 19

6.2.3. What are safeguard measures? ____________________________________________ 20

7. International trade agreements and negotiations __________________________________ 20

7.1. What are trade agreements? _________________________________________________ 20

7.2. How does the EU negotiate at multilateral level in the WTO? _______________________ 20

7.3. How does the EU conclude trade agreements? __________________________________ 22

7.4. What are the different types of EU trade relationships? ___________________________ 23

7.5. Are trade agreements enforceable? ___________________________________________ 25

8. Trade and sustainable development _____________________________________________ 25

8.1. How does the EU support sustainable development through its FTAs? _______________ 25

8.2. How are TSD chapters implemented and enforced? ______________________________ 27

8.2.1. Should the TSD chapter be subject to a general or a dedicated dispute settlement?__ 27

8.2.2. Should the EU shift to a sanction-based model for TSD chapters? _________________ 27

8.3. What does a green trade policy include? _______________________________________ 28

8.4. Do trade agreements have human rights clauses? _______________________________ 29

Table of figures

Figure 1 – EU procedure for making trade agreements ________________________________ 22

Figure 2 – Levels of depth of EU trade agreements with various partners _________________ 24

EU trade policy

5

1. Introduction

This paper charts the development of EU common commercial policy over the course of six decades,

from the Treaty of Rome to the Lisbon Treaty (Section 1.1). This development has not taken place

without controversy, as explained in Section 1.2 on the evolution and scope of trade competences.

Basic questions relating to the economics of trade in the EU are discussed in the second chapter:

these include an exploration of whether trade leads to growth (Section 2.1.), what are the effects of

trade on employment (Section 2.2.), and whether trade leads to inequality (Section 2.3.).

Chapter 3 unpacks key trade concepts such as tariffs on trade in goods, rules of origin, non-tariff

barriers to trade, and trade in services.

The aims of EU trade policy (Section 4.1.) and its formulation (Section 4.2.) are charted in Chapter 4.

Each EU institution plays a designated role in concluding trade agreements. Parliament (Section

4.2.1) is a co-legislator for trade alongside the Council (Section 4.2.3.), while the Commission (Section

4.2.2.) proposes trade legislation and negotiates on behalf of Member States. Civil society and

stakeholder involvement (Section 4.3.) is institutionalised through specific dialogues.

Chapter 5 outlines out the range of EU trade-related legislation (Section 5.1), including trade

defence instruments (Section 5.2.), which make up the protective side of EU trade policy. The next

chapter explains international trade agreements (Section 6.1.), and how they are achieved at

multilateral level (Section 6.2.) and at EU level (Section 6.3), is explained. The various types of trade

relationship (Section 6.5.) that the EU can offer trade partners and the enforceability of trade

agreements (6.5.) are also covered.

The final chapter discusses an aspect of trade policy that has been particularly important for the

European Parliament: trade and sustainable development. EU free trade agreements include a wide

range of provisions that can support sustainable development chapters (Section 7.1.). The

enforcement of the trade and sustainable development provisions (Section 7.2.) and the possibility

of a sanctions-based model (Section 7.3.) is a matter of contention. Finally, the paper covers the

specific provisions that aim to make trade policy greener (Section 7.4.) and human rights clauses in

trade agreements (Section 7.5.).

2. Background: evolution and scope of the common

commercial policy

2.1. The common commercial policy: from coal and steel to

services and foreign direct investment

The European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) was the first step taken by the six founding

members (France, West Germany, the Benelux countries (Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg),

and Italy) towards European integration and a common commercial policy (CCP). The Treaty

establishing the ECSC (signed in Paris in 1951) created a common market for the strategic

industries of steel and coal in the post-war context and introduced the free movement of products

without customs duties or taxes between the territories of the signatory states. The Treaty abolished

and prohibited import and export duties, quantitative restrictions and discriminatory measures, as

well as subsidies, State aid or special charges. The Treaty also set up the predecessor to today's

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

6

European Commission in the form of a common High Authority, which supervised the market,

monitored compliance, and ensured price transparency.

1

The Treaty of Rome, or the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community (EEC), was

signed in 1957 and became effective as of 1958. It established the EEC and a common market,

beyond coal and steel, which was based on four freedoms: the free movement of people, goods,

services, and capital.

2

In practice, the CCP emerged gradually during the 12-year transition period,

intended to smooth the establishment of the common market (1957-1969), and has continued to

evolve since.

3

A CCP was necessary because the Treaty of Rome also created a customs union, which covered

all trade in goods, abolished customs duties or equivalent charges between Member States, and set

up a common external customs tariff.

4

This was in line with the General Agreement on Tariffs and

Trade (GATT), a multilateral agreement on trade in goods – the predecessor to the World Trade

Organization (WTO). The GATT had entered into force in 1948 and required that a customs union

internally remove customs duties and quantitative restrictions on trade in goods between members,

and externally adopt the same common customs tariff in relation to third countries. Without the

common approach to trade embodied in the CCP, the European Community would have faced free-

rider problems, for instance if third country exporters entered the internal market through the

Member State where the tariffs were lowest and then took advantage of free movement across the

territory

5

. To manage this, Members States needed to pool their resources and transfer part of their

trade competences to the supranational level. The aim behind the creation of the CCP was also to

increase the Community's international bargaining power and leverage vis-a-vis third countries.

In practice, the CCP meant that common customs duties were to be fixed by the Council based on a

proposal from the Commission, which would also carry out other tasks entrusted to it.

6

The

Commission would submit the Council proposals for implementing the CCP, recommend the

opening of negotiations and then conduct them; this is still the case today.

The CCP became vital following the expansion of international trade in the 1970s, enlargements,

and the consolidation of the single market in 1986, to ensure EU competitiveness in a globalising

world. In the 1971 landmark judgment Commission of the European Communities v Council of the

European Communities on the European Agreement on Road Transport (ERTA), the European Court

of Justice (ECJ) introduced its famous 'implied powers doctrine', enabling the Community to

negotiate and conclude external agreements over a whole range of its broadly defined objectives.

7

It made this power potentially exclusive by delimiting the Member States autonomous powers on

the international scene to the benefit of the Community. The textual expression of this doctrine is

in Article 3(2) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), which provides that

the EU shall have 'exclusive competence for the conclusion of international agreements – in so far as its

conclusion may affect common rules or alter their scope'. In 1979, the ECJ issued an opinion on the

1

ECSC Treaty, Article 4. See the summaries of EU legislation.

2

Originally Article 3 of the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC), currently Article 26 of the Treaty on the

Functioning of the European Union (TFEU

). N.B.: whenever appropriate, references are made to TFEU, which originated

as the Treaty of Rome, and forms the consolidated basis of EU law.

3

Articles 110-116, Treaty of Rome.

4

Articles 28-32, TFEU.

5

A. Staab, The European Union Explained – Institutions, Actors and Global Impact, Indiana University Press. 2013,

Chapter 15.

6

Articles 31-32 TFEU.

7

ECJ Case 22/70, European Agreement on Road Transport.

EU trade policy

7

International Agreement on Natural Rubber, in which it interpreted the Community competences

widely under the Treaty of Rome, stating that the Community should be able to formulate a

commercial 'policy', and not merely administer measures such as customs and quantitative

restrictions.

8

Significant multilateral-level developments took

place in the 1990s, when the focus of external

trade shifted from goods, in particular industrial

products, to encompass further areas. The WTO

was established and multilateral treaties on

services, public procurement and intellectual

property were developed. It became increasingly

important to bring these areas under qualified-

majority voting (QMV) and therefore transfer

sovereignty to the supranational level to address

radical changes to the structure of the global

economy. Against this backdrop, in 1997, the

Treaty of Amsterdam included a new ('fast-

track') provision that allowed the Council, acting

unanimously and after consulting the

Parliament, to extend the CCP to agreements

concerning services and intellectual property at

a future date without amending the Treaties.

9

The Treaty of Nice further added that

institutional provisions of the CCP would also

apply to the conclusion of international

agreements in services and commercial aspects

of intellectual property (IP), except for agreements relating to trade in cultural, audio-visual,

educational, social and human health services, which would remain within the shared competence

of the Community and its Member States.

10

The Treaty of Nice also provided for international

agreements in the field of transport to remain outside the CCP.

11

The Treaty of Lisbon (or Lisbon Treaty), which came into force in 2009, granted substantially more

power in trade policy to the European Parliament. With an expanding trade agenda, it was important

to enhance democratic legitimacy in the policy area by increasing Parliament's role. Parliament

became a full-fledged co-legislator in the area of trade, having to give its consent to the conclusion

of trade agreements and adopt trade legislation under the ordinary legislative procedure.

12

Article 207 TFEU forms the basis of EU external trade policy today. It extended the CCP to cover all

trade in goods and services, the commercial aspects of intellectual property, as well as foreign direct

investment (FDI). With the Lisbon Treaty, all four modes of supply for trade, as defined in the General

Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) fell under the CCP. The Lisbon Treaty also reformed the

EU's external policy and recognised the interlinkage between foreign policy and international trade.

This meant that the CCP has to abide by the same principles as the EU's external action, and resulted

8

Opinion 1/78.

9

Treaty establishing the European Community (Amsterdam consolidated version), Article 133(5) (ex. Article 113).

10

Article 133(5) TEC (Nice consolidated version).

11

Article 133 TEC, ibid.

12

L. Van den Putte, F. De Ville, J. Orbie, The European Parliament's New Role in Trade Policy: Turning power into impact,

CEPS Special Report No 89, May 2014.

Key treaty developments for EU trade

ECSC Treaty, or the Treaty of Paris (signed in

1951, in force from 1952 to 2002), created a

common market for coal and steel, which was

integrated into the Treaty establishing the

European Community after expiry.

Treaty of Rome (signed in 1957, in force since

1958), establishing the European Economic

Community (EEC), created the common market

beyond coal and steel, based on four freedoms,

and the customs union.

Treaty of Amsterdam (signed in 1997, in force

since 1999) and Treaty of Nice (signed in 2001, in

force since 2003) added provisions furthering the

inclusion of services and commercial aspects of

intellectual property rights (IPR) in the CCP.

Treaty of Lisbon (signed in 2007, in force since

2009), is known in its updated form as the Treaty

on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU), and forms

the constitutional basis for the EU and its

exclusive trade competence today.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

8

in a need to enhance coordination between the EU's foreign and trade policy goals. In practice, this

meant close cooperation in particular between the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the

European Commission's Directorate-General (DG) for Trade, as well as the DGs for International

Cooperation and Development and for European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement

Negotiations and other DGs.

2.2. Evolution and scope of trade competences

The EU has exclusive competence with respect to the CCP.

13

This means that the EU, on behalf of all

the Member States, is responsible for external action in the field of trade including trade-related

legislation and international trade agreements. Yet, the exclusive trade competence has not

developed without controversy. Member States have been concerned about the loss of formal

power over trade throughout treaty reforms, although they retain ultimate decision-making power

in the Council (see Section 4.2.3.).

14

Exclusive competence applies to all areas where an agreement would have implications for

common EU rules. The Treaty of Rome did not contain a clear definition of what was to be exclusive

competence in the area of CCP. Instead, it set out the following non-exhaustive list of example

measures belonging to the CCP:

15

With time, successive treaty changes and opinions of the ECJ clarifying competences, the scope of

the CCP has evolved. Since the Lisbon Treaty, EU has had exclusive responsibility for trade in goods

and services, commercial aspects of intellectual property (IP) (e.g. patents), public procurement, and

FDI. For the conclusion of agreements in the fields of services, commercial aspects of IP and FDI, the

Council shall act unanimously where this is required for the adoption of internal rules.

16

In areas

where the EU has adopted specific common rules, for example customs, Member States cannot sign

agreements with non-EU countries that affect those rules.

17

Shared competence means that both

Member States and the EU have the power to adopt legally binding acts or international agreements

and refers to a number of pre-defined areas.

18

The Council votes by common accord (agreement of

all Member States) when trade agreements cover areas of shared competence.

Determination of the legal basis of a trade agreement, and thus the competence, can have

important political and procedural implications for the conclusion of EU trade agreements. With the

Lisbon Treaty, the CCP was extended to services, commercial aspects of IP and FDI. The EU-

Singapore Agreement became a test for the precise delimitations of these new areas of exclusive

13

Article 3(1)(e) TFEU.

14

See for example recent ECJ-cases: Opinion 1/17 (CETA), Opinion 3/15 (Marrakesh Agreement), Opinion 2/15

(Singapore) and Opinion 1/15 (Passenger Name Records).

15

Articles 110-113 Treaty of Rome.

16

See also ECJ Opinion 1/94 confirming that trade-related aspects of IP and services, with some exceptions, were a shared

competence and hence requiring unanimity.

17

See also ECJ Case 22/70.

18

Article 4(2) TFEU.

● changes in tariff rates,

● the conclusion of tariff and trade agreements,

● the achievement of uniformity in measures of liberalisation,

● export policy,

● measures to protect trade such as those to be taken in case of dumping or subsidies.

EU trade policy

9

competence, in particular concerning its investment provisions. Member States considered that the

CCP covered FDI only, whereas the Commission considered the coverage potentially wider.

19

In

Opinion 2/15, the ECJ clarified that only FDI had become an EU exclusive competence, while

portfolio investment and dispute settlement were shared competences. This led to the decision

to split the EU-Singapore Agreement into two parts: the free trade agreement (FTA, EU-only) and

the investment protection agreement (IPA, mixed).

20

The same logic was applied to the EU-Japan

and EU-Vietnam agreements to speed up the ratification process. Initially, the Commission

considered the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) an EU-only

agreement but after discussions with Member States opted to submit CETA as a mixed agreement.

21

3. Economics of trade

3.1. Does trade lead to economic growth in the EU?

The theory of comparative advantage predicts that countries stand to benefit mutually from trade

as they specialise in what they produce best and buy from others that what they produce less

efficiently. Higher levels of productivity are achieved owing to economies of scale, and trade is said

to lead to economic gains in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), job growth, and diversified

consumer choice. The theory of comparative advantage helps explain international trade patterns

in the 1980s and 1990s where low-income countries and high-income countries specialised.

Comparative advantage does not account for periods of intense intra-industry trade in similar goods

and services that occurred between developed countries after the Second World War. However,

since the rise of global value chains (GVCs) in recent decades, the theory of comparative

advantage appears to apply again as producers and countries have specialised in very specific parts

of the production process.

22

Critically, as GVCs can incorporate imported parts for products

ultimately destined for export, and vice versa, the measurement of trade flows gets muddled,

making the determination of the impact of trade on growth more challenging.

Empirical literature has shown a correlation between rising international trade and growth at cross-

country level.

23

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has found

that countries with trade openness (defined as the share of imports and exports as a share of GDP)

typically also have a higher GDP per capita.

24

Possible explanations for this correlation are

efficiencies derived from competition, access to larger markets, and learning effects.

25

However,

demonstrating the causal relationship between trade and growth is not as straightforward. Later,

Rodriguez and Rodrik (2000) noted that this relationship is not a foregone conclusion.

26

At macro-

19

L. Puccio, A guide to EU procedures for the conclusion of international trade agreements, EPRS, European Parliament,

October 2016.

20

S. Hindelang and S. Schill, EU investment protection after the ECJ opinion on Singapore – Questions of competence

and coherence, Policy Department for External Policies, Study for the INTA Committee, February 2019.

21

W. Schöllmann, Is CETA a mixed agreement?, EPRS, European Parliament, July 2016.

22

I. Zachariadis, Global and regional value chains: Opportunities for European SMEs' internationalisation and growth,

EPRS, European Parliament, February 2019.

23

J.-J. Hallaert, 'A History of Empirical Literature on the Relationship Between Trade and Growth', Mondes en

développement, Vol. 135(3), 2006, pp. 63-77.

24

OECD, 'The importance of global value chains', in OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators, 2018, pp. 76-77.

25

E. Ortiz-Ospina, Does trade cause growth?, Our World in Data Blog, October 2018.

26

F. Rodriguez and D. Rodrik, Trade Policy and Growth: A Skeptic's Guide to the Cross-National Evidence, National Bureau

of Economic Research (NBER) Working paper 7081, April 1999.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

10

level, academic studies have concluded that geographical distance from other countries is a

predictor of economic growth,

27

and that international trade has a statistically significant effect on

economic growth, indicating the presence of a causal link.

28

Others have argued that it is neither

trade nor geographic distance, but the quality of institutions, such as the rule of law in a country,

that accounts most significantly for economic growth.

29

In 2019, a review of evidence by the

Peterson Institute of International Economics stated that one consistent finding across recent

literature is that 'trade reforms that significantly reduce import tariffs have a positive impact on

economic growth, on average, but as one would expect the effects differ considerably across

countries'.

30

In the EU, where economic openness, geographical distance and quality of institutions all align,

these predictions hold true both within its single market and beyond its borders. The EU single

market is itself a case in point of trade having a positive effect on growth.

31

It has been estimated

that EU GDP increased at an estimated 1.7 % between 1990 and 2015, thanks to the single market.

32

Meanwhile, even if external trade plays a role in EU economic growth, other domestic and global

drivers, including fiscal and monetary policy, are the predominant drivers of overall growth in an

economy.

3.2. Does trade create or cut jobs in the EU?

In certain cases, downward pressures on wages and jobs are attributed to trade. Trade can lead to

structural job losses as international competition or outsourcing push out domestic production in

labour markets that are exposed to exports,

such as manufacturing.

33

In recognition of

these negative effects of global trade

patterns on employment, the EU set up a

Globalisation Adjustment Fund that

Member States can mobilise to help workers

who have lost their jobs owing to structural

shifts stemming from globalisation.

Economists have pointed out that trade has

highly differential effects on jobs within

countries, at all levels of development, even

more than between countries.

34

This means

that international trade creates winners and

losers within countries depending on

exposure to external import and export

shocks. Trade can also create jobs directly in

export-driven industries, and indirectly as economic growth spills over into jobs created. In the EU,

27

J. Frankel and D. Romer, 'Does Trade Cause Growth?' American Economic Review, Vol 89(3), pp. 379-399, 1999.

28

F. Alcalá and A. Ciccone, 'Trade and Productivity', The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 119(2), May 2004, pp. 613-646.

29

D. Rodrik and A. Subramanian, 'The Primacy of Institutions', Finance & Development, June 2003.

30

D. A. Irwin, Does Trade Reform Promote Economic Growth? A Review of Recent Evidence, PIIE, May 2019.

31

E. Dahlberg, Economic Effects of the European Single Market - Review of the empirical literature, Kommerskollegium,

May 2015.

32

LE Europe, The EU Single Market: Impact on Member States, Study for AmCham EU, February 2017, p. 134.

33

E. Ortiz-Osbina, What's the impact of globalization on wages, jobs and cost of living?, Our World in Data Blog,

October 2018.

34

N. Pavcnik, The Winners and Losers from international trade, January 2019.

Key concepts for measuring trade

• Trade openness = exports and imports / GDP

• Investment openness = FDI / GDP

• Trade balance

= exports - imports

• Market access refers to the conditions (tariffs, taxes,

rules or regulations) a country has in place for

export to their market. See: the Commission's

Market Access Database

.

•

Business and investment climate is a related

concept referring to the economic and financial

conditions (including the rule of law) for operating

in a market. See the

Doing Business measure (World

Bank).

EU trade policy

11

trade integration created an estimated 3.6 million additional jobs between 1990 and 2015.

35

As of

2018, according to the Commission, trade supported 36 million export-related jobs, which are also

on average better paid in the EU and another 20 million outside the EU including in developing

countries.

36

3.3. Does trade lead to inequality in the EU?

The rise in global inequality, understood in terms either of income or wealth distribution, has often

been associated with international economic globalisation.

Inequality within countries has been found to increase with openness to trade in low- to

mid-income countries.

37

Trade has a differential impact on skilled and unskilled workers,

38

with

skilled and mobile workers indeed benefiting proportionally more, concentrating wealth in the

higher echelons of society. Different sectors can be very differently impacted, depending on the

presence of competition in the partner country. For instance, the most vulnerable EU sectors

traditionally include textiles, footwear, leather (except for the luxury end of the market), basic and

fabricated metal products, and certain manufacturing industries, while services sectors tend to be

more robust in the global arena.

39

Inequality between countries can also increase, in particular when countries at different stages of

development establish trading relationships, for instance by means of trade agreements. With

imperfect competition conditions, specialisation at different ends of production processes or social

dumping can occur. In the context of trade agreements, a key dynamic that has been argued to

entrench inequality between developed and developing countries is protection of intellectual

property rights if they confer an unfair market advantage, to patent-holders for instance.

However, openness to trade has also been found to lead to overall welfare gains – such as poverty

reduction – that would suggest a different causal relationship. The endogenous growth theory

suggests that trade-related growth also leads to increased living standards for citizens.

40

For

instance, trade tends to place a downward pressure on consumer prices for the goods traded,

meaning that the purchasing power can improve thanks to trade. The variety of goods and services

available to consumers also increases, allowing for a wider range of choice and potential economic

gains for consumers.

Finally, domestic policies including taxation, labour market conditions, as well as international

capital flows remain some of the most powerful determinants of inequality.

35

LE Europe, p. 40.

36

Z. Kutlina-Dimitrova et al., How important are EU exports for jobs in the EU?, Chief Economist Note No. 4, DG Trade,

European Commission, November 2018.

37

Pavcnik N., The impact of trade on inequality in developing countries, NBER, 2017.

38

Helpman E., Globalization and wage inequality, NBER 2016.

39

C. Salm and M.-C. André, Benefits of EU international trade agreements, Briefing European Added Value in Action, EPRS,

European Parliament, 2017.

40

P. M. Romer, 'The Origins of Endogenous Growth', The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 8, Nr 1, 1994, pp. 3-22.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

12

4. Key trade concepts

4.1. How do tariffs work?

A tariff is a tax or a duty to be paid for an import. Historically, countries have charged importers when

goods cross borders in order to reduce imports or make it more advantageous to produce the

product domestically. Most tariffs are a percentage of the import price (for example, ad valorem 5 %

to be paid on a good worth €100), but can also be a fixed fee for a certain quantity of an import (a

specific amount per kg), which is more common for agricultural imports. Tariff rate quotas (TRQs)

are two-tier instruments that charge a lower rate below a certain threshold, and jump to a higher

rate once the quota is exhausted.

Under the WTO, countries have agreed to

limit the tariffs they charge each other. For

instance, in 2017, average tariffs applied by

the three major trade players (the EU, China

and the United States (US)) were all below

10 %, which is considered relatively low.

Tariffs can be further lowered by FTAs. The

EU also has trade preference schemes that

eliminate or reduce tariffs for developing

countries (i.e. General Scheme of

Preferences, GSP+, or Everything But Arms).

The EU's tariff rates for each product and

each trading partner (e.g.: avocados from

Australia) can be checked on the

Commission's market access database.

41

In the EU, tariffs are collected on behalf of the Commission by the customs authorities of the Member

States in which goods arrive. A part is retained by Member States to pay for administrative costs,

while the rest forms a significant part of the EU budget, which, in turn, feeds back to the Member

States. High tariffs increase the price of imported goods and thus have a negative effect on trade

volumes. Because of their direct impact on trade, and even though the WTO only allows increases

in tariffs in exceptional cases, tariff hikes (or threats thereof) are occasionally used for political or

strategic purposes, as well as to extract specific concessions from trade partners.

Under the WTO, a distinction is made between most-favoured nation (MFN), preferential, bound and

applied tariffs. MFN tariffs are the highest tariffs WTO members can charge each other.

Bound tariffs are the maximum rates a country commits not to exceed for specific products, while

applied tariffs are the rates actually charged in practice, and can be less or equal to the bound tariff.

Preferential tariff rates are lower-than-MFN tariffs that countries can agree to under customs

unions or free trade agreements.

41

European Commission, Market access database.

Key data sources for trade policy-making

Useful sources for country profiles on goods and

services: Economic indicators and trade with the EU

(EPRS; European Parliament), trade statistics (European

Commission), trade profiles and Aid for Trade country

profiles (WTO)

Big data visualisation tools:

Observatory of

Economic Complexity (MIT), UN Comtrade analytics,

Atlas of Economic Complexity (Harvard)

Tariff data: for EU Member States Eurostat Comext

and Easy Comext, globally UN Comtrade or IMF

Database or OECD Stats

EU trade policy

13

4.2. What are rules of origin?

Rules of origin (RoO) identify the economic nationality of goods so as to determine the tariff

applicable and to prevent the circumvention of customs duties at the border. RoOs have an

important impact on trade flows in combination with tariff levels, in particular for products made in

many separate stages (e.g. textiles and apparel). For instance, without RoOs, products that are

mostly made in a country with which the EU does not have a preferential trade relationship could

be brought into the EU single market without paying the due tariff, by having just the final touches

added in a country that has concluded an FTA

with the EU. RoOs essentially help avoid such

situations and thus are an integral part of

every FTA. Goods need to be either 'wholly

obtained' from materials originating in

countries of the FTA, or 'sufficiently

transformed' in a country party to the FTA. In

addition, cumulation of origin can allow the

producing country to source the product in

countries that are party to the FTA and still

benefit from preferential tariffs. The EU has

concluded a regional convention on pan-

Euro-Mediterranean preferential rules of

origin that brings under a single legal

instrument all the rules of approximately

60 bilateral FTAs in the region to benefit from

common rules and cumulate origin.

Restrictive RoOs can obstruct trade in a

significant manner when they require a

particularly high amount of a product to be locally made. This is compounded by today's globalised

value chains, which mean that a significant proportion of European products' added value comes

from abroad. In the same vein, strict RoOs can influence companies' long-run investment decisions

(e.g. where to build a car factory).

4.3. What are non-tariff barriers to trade?

Non-tariff barriers (NTBs) are government measures other than tariffs that can impact exports and

imports of goods and services. NTBs can be

42

:

● protectionist measures that help domestic producers at the expense of others (e.g. local

content requirements, import quotas);

● assistance measures that help domestic producers not (directly) at the expense of third

countries (e.g. subsidies to state-owned enterprises); or

● non-protectionist policies that aim to safeguard legitimate concerns in the public interest

(such as domestic health, safety and environmental protection) but that can involve further

red tape (e.g. testing requirements for fruit). Technical barriers to trade (TBT) and sanitary

42

A. Deandorff, Non-tariff Barriers, Study for USAID, 2013.

Three basic rules are used to determine

origin:

• The value-added rule is concerned with how much

value is added in the partner country and how

much elsewhere.

• The change of tariff classification rule looks at

whether the tariff classification changes with the

final product. Tariffs are classified according to the

harmonised commodity description and coding

system ('HS codes').

• The production activities rule sets out the

production activities for the product and the

materials it must be manufactured from.

Source: Future trade relations between the EU and the UK:

options after Brexit, Policy Department for External Policy,

Study for the INTA Committee, European Parliament, March

2018.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

14

and phytosanitary (SPS) measures can fall in this category. These are also the most common

type of NTB according to a 2016 International Trade Centre (ITC) survey.

43

In practice, EU goods exporters can suffer from inadequate recognition of geographical indications

(GIs), i.e. labels protecting products linked to their geographical origin, e.g. in the form of protected

names of cheeses or wines of specific regions). In trade in services NTBs range from visa restrictions

and failure to recognise European workers' qualifications, to difficulties establishing local presence

or limits to cross-border data flows for European companies. Several WTO rules deal with NTBs, for

instance, with regard to import licensing procedures and customs valuation rules. EU FTAs can go

further in removing NTBs and behind-the-border barriers; this is also a central objective of trade

negotiations. Nevertheless, in practice, NTBs persist in the EU single market, especially in the services

sector,

44

even though quantitative restrictions and measures having an equivalent effect are

forbidden by the Treaty of Lisbon (Article 34) between Member States. This can be interpreted as a

prohibition of NTBs. While it is particularly difficult to quantify the impact of NTBs, research has

suggested that potential global trade in merchandise could increase by 9.7 % if action was taken to

address NTBs in the areas of ports, customs, regulation and service sector infrastructure.

45

4.4. How are services traded?

Unlike goods, services have no physical form. The key multilateral legal framework regulating trade

in services between WTO Members is the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS), which

sets out four specific modes through which services can be traded:

● mode 1: cross-border supply (e.g. advisory services, insurance or financial services),

● mode 2: consumption of a service abroad (e.g. tourism, repairs),

● mode 3: commercial presence of the supplier (e.g. establishment of affiliate offices abroad

or FDI),

● mode 4: presence of natural persons (e.g. consulting, construction services).

Commercial presence, which is essentially investment, is the most common mode for EU services

exports to third countries (60 % in 2015),

46

followed by cross-border supply. A fifth mode has been

suggested covering services that are incorporated or embedded in the production processes of

traded goods (e.g. engineering or software design services). In theory, this would account more

accurately for today's increasingly digital trade patterns, but it would be difficult to implement in

practice. Under the GATS, the EU presents a single schedule of services commitments in line with its

CCP. Within these commitments, Member States make their own limitations to their commitments.

The EU tends to have more limited schedules for mode 4, except for specific categories mostly of

high-skilled suppliers. Indeed, as EU services exports exceed merchandise exports in terms of value,

the importance of services trade to the EU economy cannot be underestimated. However, data

collection is a particular problem when it comes to trade in services (as opposed to goods). Most

statistical offices do not publish services trade data by mode of supply even if pilot efforts have been

made by the Eurostat and the OECD.

43

ITC and European Commission, Navigating non-tariff measures, 2016.

44

M. Szczepanski, M., Understanding non-tariff barriers in the single market, EPRS, European Parliament, October 2017.

45

J. Wilson, C. Mann, and T. Otsuki, Assessing the Potential Benefit of Trade Facilitation: A Global Perspective, World Bank

policy research working paper 3224, February 2004.

46

Eurostat, Services trade statistics by modes of supply, 2019.

EU trade policy

15

5. Formulation of EU trade policy

5.1. What are the aims of EU trade policy?

While its specific direction is subject to political agreement, in recent decades, EU trade policy has

largely been characterised by a commitment to more open and free trade, which is considered to

lead to growth and jobs. Since the 1980s, the Commission has broadly pursued market access and

trade liberalisation, both in terms of tariffs and NTBs, with the exception of trade defence, even if

the specific aims are more nuanced in different areas of trade policy.

47

Reasons for this suggested in

academic literature include Member States' delegation of liberalisation to the supranational level,

48

bureaucratic expansionism, business pressures, and genuine beliefs in the 'win-win' nature of

international cooperation and trade.

49

EU trade policy also aims to abide by the precautionary

principle, as enshrined in the TFEU. This means that the EU prefers to play on the safe side where

there are grounds for concern about dangerous effects on the environment, human, animal plant

life, or health. Within these broad principles, specific objectives of EU trade policy are set out in the

most recent Commission strategy or communication for trade, and are subject to political change.

In 2006, in the context of the suspension of the WTO Doha Round, the Global Europe: Competing in

the world

50

communication highlighted the need for EU trade policy to be flexible so as to adapt to

the rapidly changing environment, and initiated a period of concentrated focus on FTAs

stretching beyond the EU's neighbourhood or former colonies. It also suggested that the new FTAs

would need to be 'comprehensive and ambitious in coverage, aiming at the highest possible degree

of trade liberalisation, including in services and investment'. This has resulted in the development

of a new generation of FTAs, which tackle NTBs and regulatory issues, as well as the traditional

market access, in a more concentrated manner. A key rationale behind FTAs is to spread EU

regulatory practices, standards and norms to partner countries and to ensure that trade takes place

on the basis of rules.

In 2015, the 'trade for all' strategy

51

set out to make trade policy more effective, transparent and to

pay special attention to values within the EU, by being responsive to the public's expectations on

regulations and investment, and outside the EU, by promoting sustainable development, human

rights and good governance. The strategy also highlighted the importance of the multilateral

rules-based trading system, as embodied by the WTO.

As of 2019, the EU has focused increasingly on a trade policy that protects in the context of trade

threats from the US and seeks to 'level the global playing field' and improve reciprocity in the

context of the rise of China.

52

The Commission, Parliament, and the Council have all reiterated their

support for the multilateral rules-based trading system; strengthening it in the face of global trade

challenges is a top priority of EU trade policy.

47

A. Young and J. Peterson, Parochial Global Europe: 21st Century Trade Politics, Oxford University Press, 2014.

48

S. Meunier, Trading Voices: The European Union in International Commercial Negotiations, Princeton University Press,

2005.

49

Bollen, Y., 'EU trade policy', Handbook of European policies: interpretive approaches to the EU, 2018.

50

Global Europe - Competing in the world - A contribution to the EU's Growth and Jobs Strategy, COM(2006) 567,

European Commission, October 2006.

51

Trade for all - Towards a more responsible trade and investment policy, COM(2015) 497, European Commission,

October 2015.

52

EU Commissioner for Trade Cecilia Malmström's speech on trade trends, January 2019.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

16

5.2. What are the roles of EU institutions in trade policy?

5.2.1. What does the European Parliament do?

In 2009, the Lisbon Treaty gave Parliament full legislative power in the area of trade. Under the

ordinary legislative procedure, Parliament and Council are on an equal footing for the adoption of

trade-related acts proposed by the Commission.

The Lisbon Treaty also increased Parliament's formal powers on international trade agreements.

The Commission must inform the Parliament at all stages of negotiations. Most importantly,

Parliament has a veto over trade agreements at the ratification stage when it must give its consent

to the conclusion of an agreement with a yes/no vote. For mixed-competence agreements, Member

State parliaments ratify in accordance with their own national procedures.

In practice, the European Parliament exercises a monitoring function that goes beyond the

consent procedure. It can choose to adopt resolutions on the opening of negotiations and, over the

course of negotiations, hold public hearings or workshops, and carry out relevant studies.

Increasingly, Parliament also scrutinises the ex-post implementation of trade agreements with its

implementation reports, in particular since the emergence of Parliament Committee on

International Trade (INTA) technical briefings and monitoring groups, support from the dedicated

studies commissioned by the Policy Departments, and the creation of the European Parliamentary

Research Service in 2013, which provides independent analytical support. Finally, at multilateral

level, Parliament participates in the work of the Steering Committee of the WTO Parliamentary

Conference, and contributes to the Commission's work in the WTO with resolutions and reports.

Parliament is also required to give its consent to WTO agreements as with other international

agreements.

5.2.2. What does the European Commission do?

The European Commission has a central role in EU trade policy on account of the exclusive EU

competence. It proposes EU trade legislation and also prepares and negotiates EU trade agreements

with third countries (See Section 6). The Commission also publishes trade policy strategies, and

implements EU trade policy. This can involve updating EU trade legislation through delegated and

implementing acts.

Much of the literature on EU trade policy has focused on the dynamics between EU institutions. On

the basis of principal-agent theories, it has been argued that the Commission is the primary agenda

setter, owing not least to information asymmetries and Commission autonomy when it comes to

trade.

53

5.2.3. What does the Council do?

With regard to trade agreements, Council authorises the opening of negotiations and decides on

the conclusion of the agreement following the vote in Parliament. Council follows the negotiations

closely. More specifically, the Trade Policy Committee (TPC) assists and advises the Commission in

negotiations with third countries and in WTO-related work. The TPC meets monthly in its full-

member configuration and the TPC deputies meet weekly. The TPC has also other configurations,

namely on services and investment, steel, textiles and other industrial sectors and mutual

recognition agreements.

53

Y. Bollen.

EU trade policy

17

Both trade agreements and trade legislation are adopted in the Council on the basis of qualified-

majority voting, which means that the agreement needs to be supported by 55 % of Member States,

representing 65 % of the population. However, in practice, Council adopts decisions by common

agreement in areas of shared competence (e.g. commercial aspects of IP).

In academic papers, Member States' positions on trade are often characterised as 'given' or fixed

(e.g. along the North-South divide), when it comes to being for or against free trade. However,

Member States' approaches can be fluid and multidimensional leading to heterogeneous

constellations taking place on specific areas of trade policy.

5.3. How is civil society involved in EU trade policy?

The role of stakeholders in feeding into EU trade policy is largely institutionalised. The Commission

holds several public consultations per year on trade-related issues whereby stakeholders can

express their views and provide data. The Commission publishes the proposals and a synopsis report

after the consultation. The Commission also organises civil society dialogues (CSD) on trade issues,

which discuss key concerns and seek to improve policies. Business representatives and

confederations of industries attend the dialogues particularly actively. FTAs contain provisions for

the creation of domestic advisory groups and civil society fora, which are organised on the EU-side

by the European Economic and Social Committee (EESC). Parliament voices civil society concerns in

its resolutions and organises public hearings where stakeholders have a chance to exchange views

with decision-makers. At Member State level, each country consults their stakeholders on trade

policy formulation in line with their national processes.

According to academic literature, businesses have a slightly higher success in influencing outcomes

relative to other actors such as NGOs in EU trade policy, as predicted by rationalist political economy

perspectives.

54

Nevertheless, civil society campaigns have led to several policy reversals. Cases in

point include the rejection of the anti-counterfeiting trade agreement (ACTA), the Commission

yielding to core demands (e.g. on transparency) in the context Transatlantic Trade and Investment

Partnership (TTIP) talks between the EU and the US, and the criticism of investor-state dispute

settlement provisions in EU FTAs, notably CETA.

54

A. Dür, 'Measuring Interest Group Influence in the EU', European Union Politics, 2008.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

18

6. EU trade-related legislation

6.1. What are the different EU laws relating to trade?

EU legislation in the area of trade is adopted by the ordinary legislative procedure. EU trade-related

legislation can be both horizontal and country-specific. Legislation in other areas such as customs,

enlargement or foreign policy, also have important interlinkages with trade.

55

55

Eur-lex summaries of trade legislation.

Key EU trade-related legislation

Investment

• Bilateral investment treaties (BITs) (1219/2012)

• Disputes between foreign investors and EU governments (912/2014), clarifying whether the EU

or Member States pay the costs for claims

• FDI screening framework (2019/452)

Trade defence instruments

(see also Section 5.2.)

EU Enforcement Regulation provides the legal basis for the EU to suspend concessions under WTO

Imports and exports, specific products

• Codified common rules for imports (2015/478) and codified common rules for exports (2015/479)

• Exports of cultural goods (required licences 116/2009)

• Dual-use export controls (428/2009)

• Trade arrangements (i.e. export refunds and imports duties) for processed agricultural products

(510/2014)

• Export credit insurances (Directive 98/29/EC) protecting exporters against non-payments by

foreign buyers

• Common rules for the application of safeguard measures to imports from certain non-EU

countries (namely non WTO countries i.e. Azerbaijan, Belarus, North Korea, Turkmenistan and

Uzbekistan) if they may cause serious injury or threat to EU producers (2015/755)

• Imports of textile products from certain non-EU countries, namely North Korea (2015/936)

• Trade in seal products (1007/2009), which was also the subject of the famous WTO dispute EC-

Seal Products (DS400)

• Allocation of import and export quotas and licences (717/2008)

Sustainable development

• Generalised tariff preferences (978/2012) set out rules for general scheme of preferences (GSP),

GSP+ incentive scheme, and the full tariff- and quota-free imports under 'Everything But Arms'

(EBA)

• Trade in conflict minerals laying down due diligence obligation (2017/821)

• Trade in rough diamonds (implementing the Kimberley process certification system) (2368/2002)

EU trade policy

19

6.2. What are trade defence instruments?

If EU commitments under the WTO constitute the multilateral sphere and EU FTAs represent the

bilateral aspects of trade policy, EU trade defence instruments (TDIs) can be viewed as unilateral

measures the EU can resort to in order to protect its market in the context of open markets.

56

TDIs

are not protectionist measures. For the EU, they are based on WTO rules, specifically the

Anti-dumping Agreement (ADA) and the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing

Measures (ASCM). TDIs were modernised in 2018, along with a new methodology for calculating

dumping margins (adopted in 2017) and they seek to protect European companies against unfair

trade practices.

57

6.2.1. What are anti-dumping duties?

Dumping occurs when foreign products are sold at an artificially low price in the EU. This can involve,

for instance, non-EU product imports supported by distorting subsidies or other support measures,

for instance in order to gain a market share (predatory dumping) or sporadically to offset a

temporary surplus of a product. To counter this, the EU can impose anti-dumping duties, which are

the most commonly used TDI in practice. The Commission can autonomously adopt preliminary

anti-dumping measures, and only a rejection by qualified majority in the Council can reverse them.

The Parliament does not play a formal role for individual duties, but can adopt resolutions and

co-legislates the underlying legislative framework under the ordinary legislative procedure.

Following an evidence-based complaint, the Commission can open investigations into whether

there is dumping by the producers in the third country concerned, whether EU industry has suffered

material injury (defined in Article 3 ADA), and whether a causal link exists between dumping and

injury. Finally, the Commission checks that putting anti-dumping duties in place does not work

against the European interest. When anti-dumping measures are imposed, they take the form of an

ad valorem duty, a fixed amount on the price of a product or a minimum import price on the good

in question. According to the 'lesser duty rule', these amounts cannot be higher than what is needed

to prevent injury to EU producers.

58

The exporter can also commit to importing the good above a

minimum threshold, which is called a price undertaking.

6.2.2. What are anti-subsidy measures?

Countries have the right to subsidise their domestic producers, except for certain subsidies and

support measures that are set out in the WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures

(ACSM).

59

The key concept in anti-subsidy policy is 'injury', which means the EU needs to

demonstrate that its domestic producers are harmed by the third country's practices. When a

complaint brings evidence of injury, the Commission launches an investigation into whether the

imports in question benefit from countervailable subsidies (i.e. actionable subsidies, as defined in

the ACSM), whether EU industry is injured and, crucially, whether a causal link exists between the

injury and the subsidised imports. Finally, the Commission verifies whether putting up

countervailing measures would be in the EU interest.

60

Anti-subsidy measures aim to counteract

distorting subsidies. They can take the form of a percentage of the price of the good, a fixed

56

Y. Bollen.

57

European Commission, Europe's trade defence instruments now stronger and more effective, June 2018.

58

Trade defence instruments: Council agrees negotiating position, Council of the European Union, 2016.

59

WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures, full text.

60

Anti-subsidy policy, European Commission.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

20

premium on an amount (per unit) of the product, a minimum threshold import price, or a price

undertaking where the exporter offers to sell the product above a minimum price rather than be

subjected to a measure.

6.2.3. What are safeguard measures?

Safeguard measures differ from anti-dumping and anti-subsidy measures in their underlying logic,

which does not focus on fairness. Safeguards (i.e. temporary withdrawal of tariff preferences) can be

put in place when an EU industry is suddenly faced with an unforeseen and sharp rise in imports;

they are therefore used very sparingly.

61

When a Commission investigation concludes that

safeguard measures are warranted (along specific and strict criteria), they can impose quantitative

restrictions (i.e. import quotas or tariff quotas that would otherwise be prohibited) and surveillance

such as a system of automatic import licensing. There are two separate safeguard regulations, one

for WTO countries (Regulation 2015/478) and another for non-WTO countries (Regulation

2015/755). In addition, under FTAs, the EU can also apply safeguards in cases of import increases

that threaten to seriously injure domestic industry. This was streamlined in 2019 into the Horizontal

Safeguards Regulation (2019/287).

7. International trade agreements and negotiations

7.1. What are trade agreements?

Trade agreements aim to liberalise trade, either by removing or reducing customs duties, or by

abolishing non-tariff barriers to trade (NTBs). They can be multilateral (WTO), bilateral (e.g. FTAs),

regional, or plurilateral (certain WTO agreements, e.g. on e-commerce). The EU's objectives range

from purely economic (gaining market access and facilitating low-cost imports), political or strategic

(arguably in the Eastern Partnership), to decreasing NTBs, promoting EU's approach to managed

globalisation,

62

or even achieving regulatory alignment to EU norms and standards. Contrary to

what is often argued, academic research has found that the EU has not focused on exporting its

regulations through new generation FTAs.

63

Others have studied more broadly the liberal discourses

associated with trade and the proliferation of FTAs in the EU.

64

7.2. How does the EU negotiate at multilateral level in the WTO?

Because of the CCP, the EU acts as a single actor in the WTO. In practice, this means, for instance,

that the Commission negotiates on behalf of the Member States in the WTO and represents them in

the General Council of the WTO as well as other subsidiary WTO bodies. The EU Trade Commissioner

represents the Member States at the WTO ministerial meetings. The Commission reports regularly

to Council and Parliament on multilateral negotiations and developments. It seeks a green light

from Council for negotiations, and needs authorisation from both Council and Parliament to sign an

agreement. Parliament also monitors WTO activities through the Parliamentary Conference on the

61

European Commission, Safeguards.

62

R. Abdelal and S. Meunier, 'Managed globalization: doctrine, practice and promise', Journal of European Public Policy,

Vol. 17( 3), Taylor&Francis Online, 2010, pp. 350-367.

63

A. Young, 'Liberalizing trade, not exporting rules: the limits to regulatory co-ordination in the EU's 'new generation'

preferential trade agreements', Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 22(9), Taylor & Francis Online, 2015,

pp. 1253-1275.

64

Y. Bollen.

EU trade policy

21

WTO, which it organises jointly with the Inter-Parliamentary Union. The conference is a forum where

MEPs can influence the direction of discussions within the WTO in annual meetings. On the basis of

files prepared by its Legal Service and DG Trade, the Commission also launches disputes and handles

the cases in the dispute settlement mechanism, with Council support. It also proposes potential

retaliatory measures to the Council.

EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service

22

7.3. How does the EU conclude trade agreements?

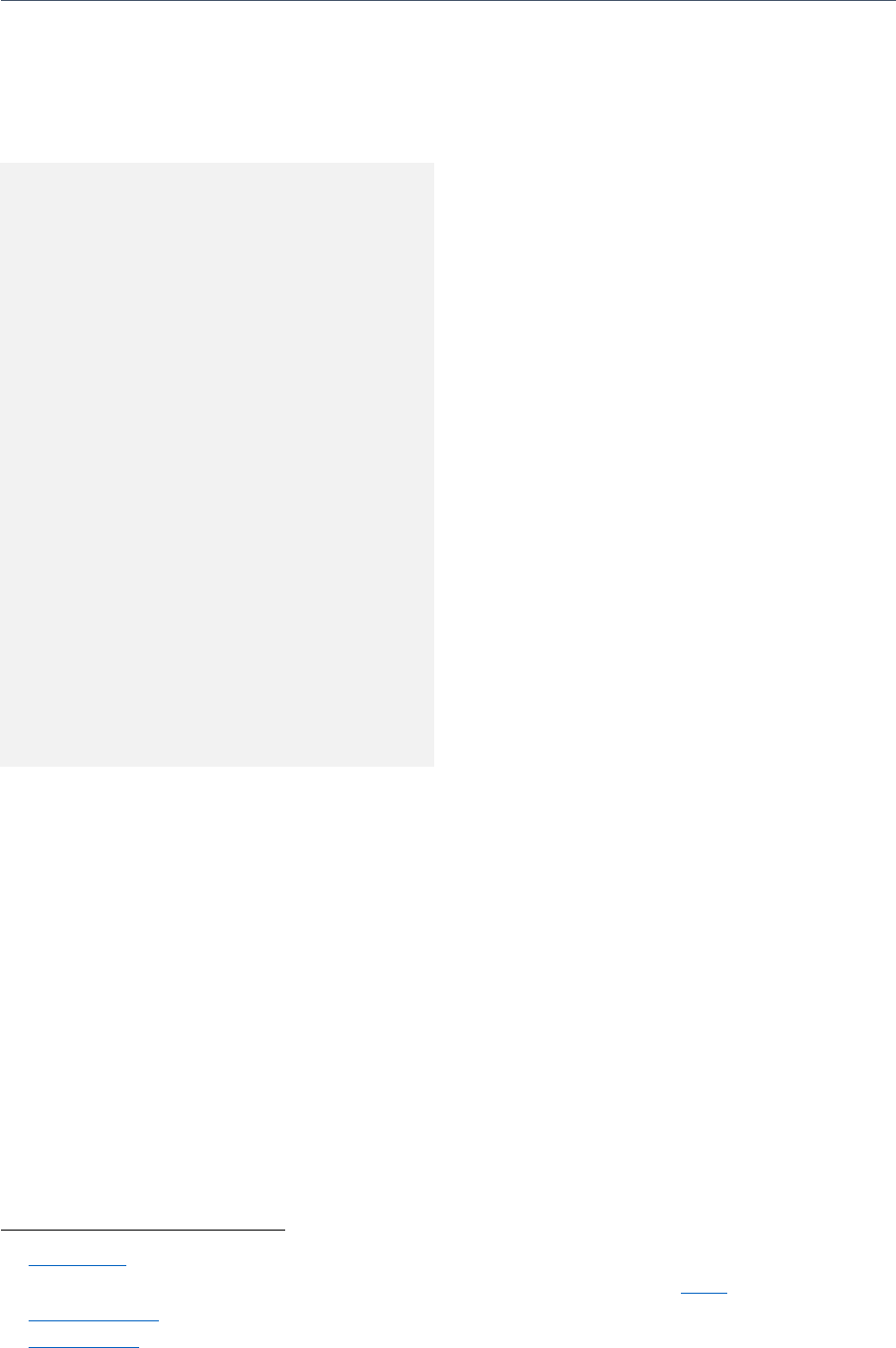

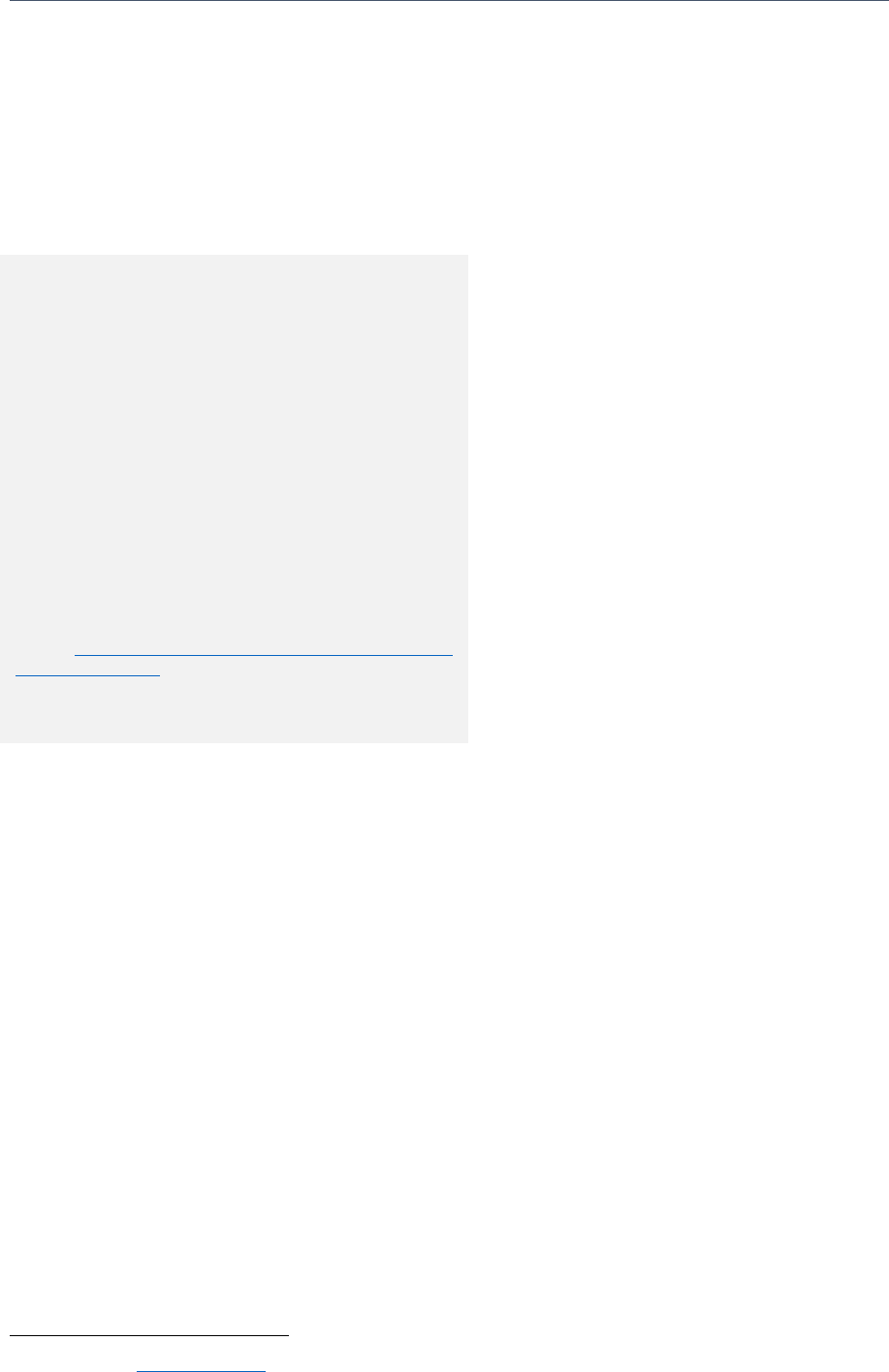

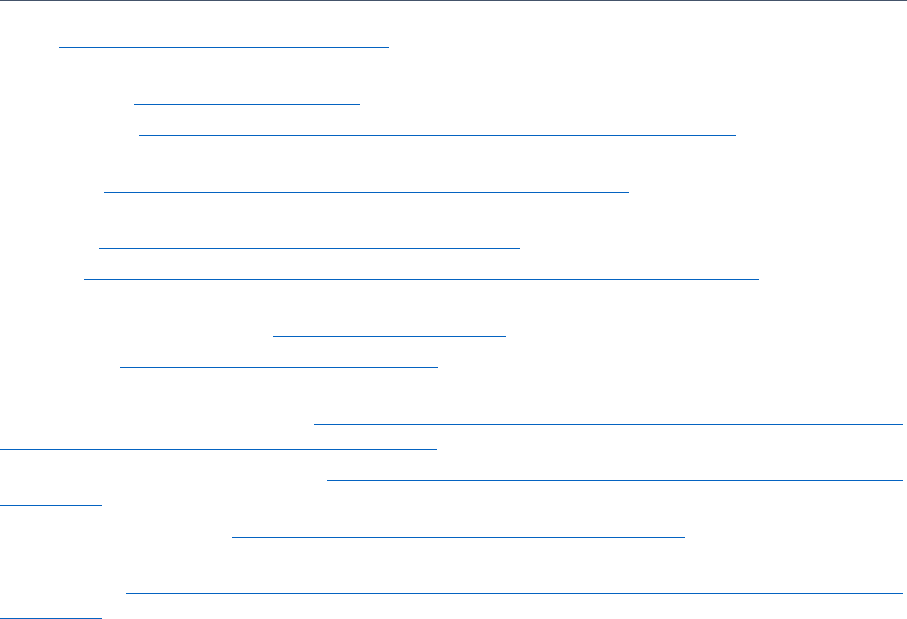

Figure 1 – EU procedure for making trade agreements

Source: Author. For further details, see: L. Puccio, A guide to EU procedures for the conclusion of international

trade agreements, EPRS, 2016.

Preparation

•The Commission holds a public consultation, informal dialogues and a scoping exercise

to determine areas for the negotiations.

•The Commission issues a recommendation for a Council decision authorising the

opening of negotiations (with draft negotiating directives and, where relevant,

supporting analysis), sometimes referred to as the draft negotiating mandate.

Decision to

open

negotiations

•Council votes (formally by QMV, but consensus is preferred) on the Commission proposal to open

negotiations. If authorised, a negotiating mandate is issued. The Council decision can be accompanied

by the negotiating directives.

•Parliament can issue a non-binding resolution on the opening of negotiations, or after the adoption of

the mandate. Council may choose to wait for the Parliament vote before making its decision.

Negotiations

•The Commission publishes reports on negotiating rounds and initial proposals online. On average, FTA

negotiations take two to three years. A sustainability impact assessment (SIA) is conducted.

•Council's Trade Policy Committee (TPC) gets regular reports from the Commission. The text proposals

of the Commission must be agreed with the Council before they are tabled for negotiations.

•Parliament gets updates from the Commission on the progress with the negotiations to help determine

whether or not there is political support, given that Parliament must ultimately approve. Parliament

can contribute with resolutions on the progress of negotiations.

Agreement on

text

•The Commission informs Parliament, Council and the public when negotiations result in an 'agreement

in principle' on a single text. Shortly after, in line with its transparency policy, the Commission publishes

the entire text of the draft agreement.

•The Commission carries out the legal review, or 'scrubbing', to check for consistency. In practice, delays

may occur at this stage if the EU or partner country are still due to deliver on outstanding issues.

Initialling the

agreement

• The Commission lead negotiator with a counterpart from partner country initial the entire agreement

(not yet legally binding). The Commission sends the Council and Parliament the text of the agreement

to prepare it for signature.

•The Commission makes proposals to the Council on decisions to sign, provisionally apply (partially or

fully, depending on the legal basis) and conclude the trade agreement.

Signature of

the

agreement

•Council adopts a decision to sign the agreement (i.e. a decision signalling the intention to conclude)

and indicates a date for signature. At this stage, the Council also requests the consent of the Parliament

for the conclusion of the agreement.

•The EU and the partner country formally sign the agreement. The Council sends the agreement to

Parliament for consent ('saisine').

Provisional

application

•Parliament votes in plenary on whether they approve the agreement or not following the report and

vote of the trade committee (INTA) on the agreement.

•It has become standard practice to wait until Parliament has voted before starting provisional

application. The agreement is provisionally applied fully or partially depending on whether the

content is an exclusive or shared competence. In practice, provisional application can continue

indefinitely unless one of the parties signals that it will not approve the agreement.

Entry into

force

•Council adopts a formal decision (QMV as specified in Article 218 TFEU with certain exceptions) to

conclude the agreement.

•The parties notify each other of the completion of their respective ratification procedures, and the

agreement enters into force and is published in the EU's Official Journal.

•Mixed agreements must be ratified in Member States, in line with national procedures, before they

enter into force.

EU trade policy

23

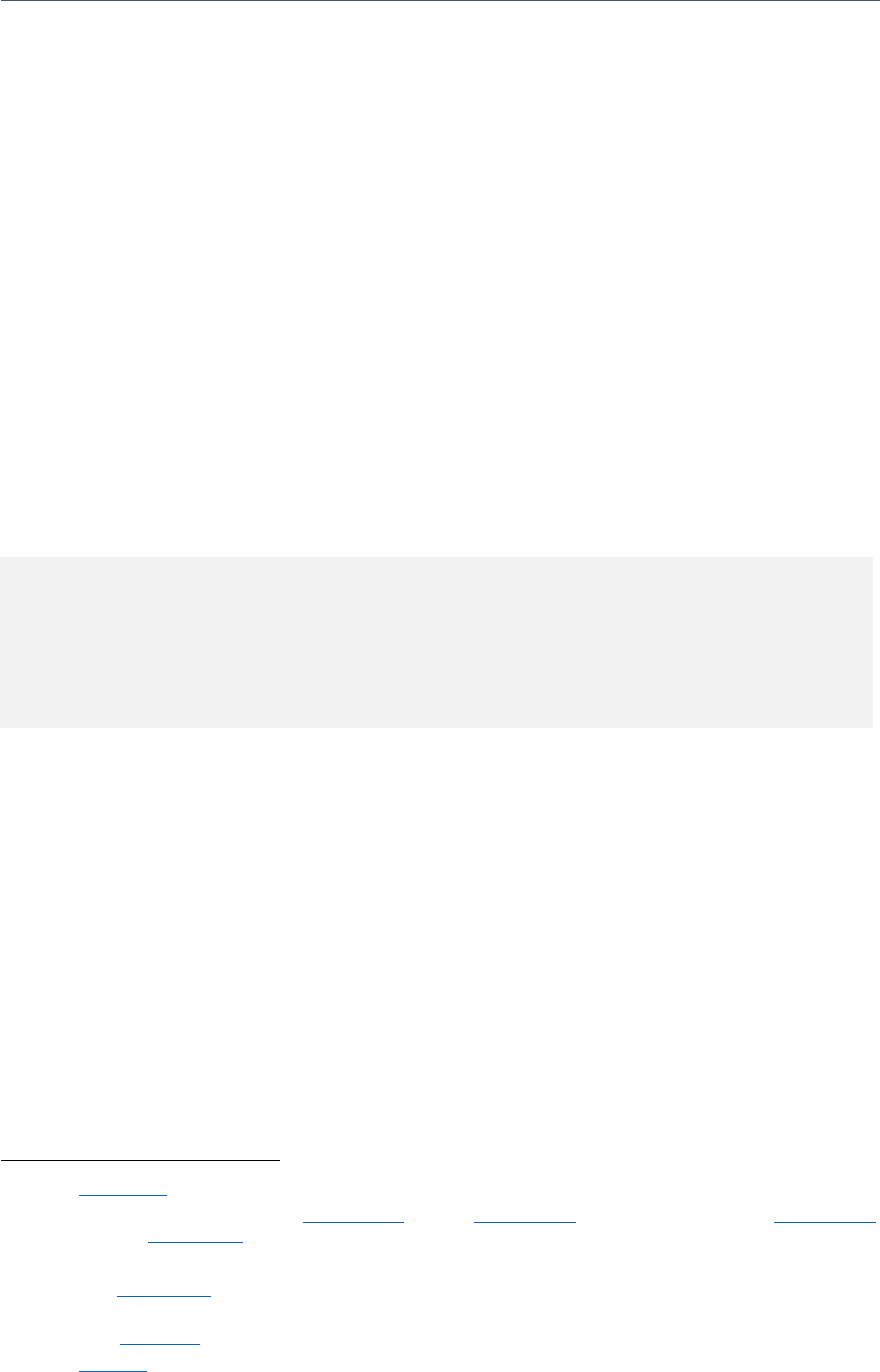

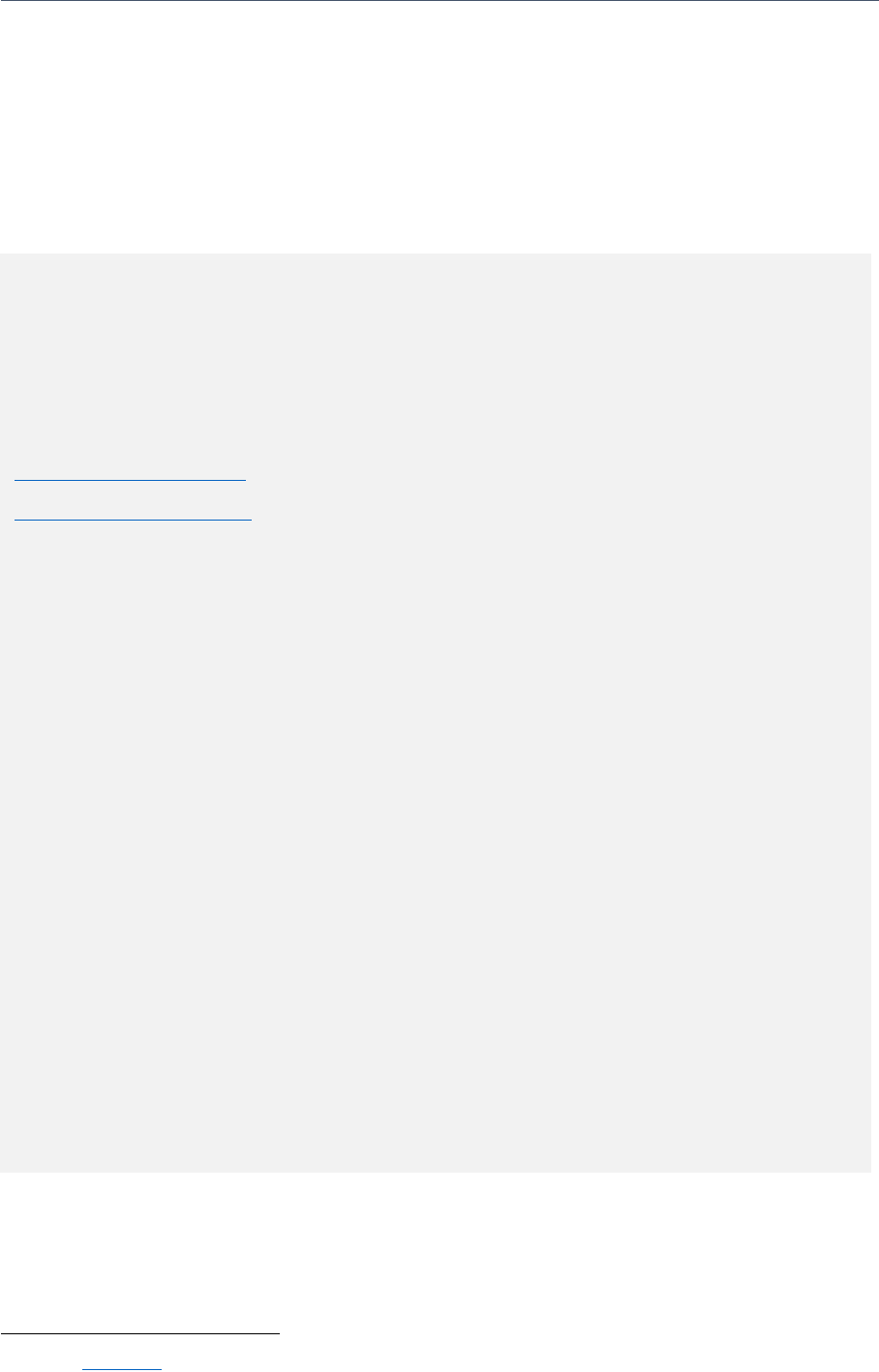

7.4. What are the different types of EU trade relationships?

FTAs do not exempt the EU from WTO rules, but allow the EU to go further with a trade partner

providing certain WTO conditions are met. An important condition is that the trade agreement

should cover 'substantially all trade' (GATT Article XXIV). Whilst there is no exact definition of what

constitutes substantially all trade, the general principle is that the EU cannot conclude a trade

agreement on specific sectors only, e.g. just cars.

The EU has different trade relationships with partner countries.

65

These are not models per se, as for

instance the trade relationship between the EU and Switzerland is very specific as it arose

incrementally over decades. The deepest trade relationship with the EU is EU membership itself. This

implies, among other aspects, membership of the single market, participation in the four freedoms,

and exclusive EU competence over trade policy. Beyond that, some of the main trade relationships

that the EU can propose to its trading partners, ranging from deep to shallow, are listed in Figure 2.

66

65

P. Eeckhout, Future trade relations between the EU and the UK: options after Brexit, Policy Department for External

Policies, Study for INTA Committee, European Parliament, 2018.

66

Typologies of trade relationships can be conceptualised in several ways, also see breakdown by type of FTA by DG